- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Lung cancers arise from malignant epithelial cells in the lungs. Globally, lung cancer is the most common cancer (11.6% of new cancer diagnoses) and is the leading cause of cancer death (18.4% of total cancer deaths).1

In the UK, the incidence of lung cancer is 43,000. On average, a full-time general practitioner diagnoses approximately one case of lung cancer every year.2

Despite its prevalence, lung cancer has a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 17%.3

Aetiology

Classification of lung cancer

Lung cancers are split into two categories: non-small cell carcinoma (85%) and small cell carcinoma (15%). This distinction is based on the size of the malignant cells seen on microscopy.

Non-small cell carcinomas are further classified as adenocarcinoma (40% of all lung cancer), squamous cell carcinoma (30%) and large cell carcinoma (10%).4 Table 1 illustrates important features of each lung cancer subtype.

Table 1 Important features of lung cancer subtypes5

| Lung cancer type | Pathology | Clinical features | |

| Non-small cell carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma | Located peripherally (in the smaller airways)

Histology: glandular differentiation |

More common in non-smokers and Asian females

Metastasise early Responds well to immunotherapy |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Located centrally (in the bronchi)

Histology: squamous differentiation (keratinisation) |

More common in smokers

Secrete PTHrP, causing hypercalcaemia Metastasise late (via lymph nodes) |

|

| Large cell carcinoma | Located peripherally and centrally

Histology: large and poorly-differentiated |

More common in smokers

Metastasise early |

|

| Small cell carcinoma | Located centrally

Histology: poorly-differentiated |

More common in older smokers

Metastasise early Secrete ACTH (Cushing’s syndrome) and ADH (SIADH) Associated with Lambert-Eaton syndrome |

|

Risk factors

The main risk factor is tobacco smoking, which is associated with 80% of lung cancer cases.6

Other important risk factors include:

- Air pollution (indoor and outdoor)

- Family history of cancer, especially lung cancer

- Male sex

- Radon gas (typically affects miners)

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of lung cancer include:

- Unexplained cough for at least 3 weeks (with or without haemoptysis)

- Unintended weight loss (>5% in 6 months)

- New-onset dyspnoea

- Pleuritic chest pain (due to the tumour invading the pleura or the chest wall)8

- Bone pain (due to metastases – commonly the spine, pelvis and long bones)9

- Fatigue (due to anaemia of chronic disease)

Note that up to 20% of patients present with non-respiratory symptoms (such as fatigue).10

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Family history: lung cancer in a first-degree relative is associated with a doubling in the risk of developing lung cancer.7

- Smoking history: quantify in pack-years (1 pack-year = smoking 20 cigarettes a day for a year). Also ask about passive smoking (second-hand smoking), as this can cause lung cancer.11

- Occupation: may be exposed to indoor air pollution or radon gas (e.g. miners).

Clinical examination

A full respiratory examination should be performed in suspected cases of lung cancer. See the Geeky Medics guide here for further information.

Typical clinical findings in lung cancer include:

- Cachexia: cancer can cause increased resting energy expenditure and lipolysis.12

- Finger clubbing (Figure 1): the exact mechanism is unknown, but it may be due to increased secretion of growth factors, leading to the growth of the extracellular matrix in the nails.13

- Dullness to percussion: due to the tumour (solids are less resonant than gases).

- Cervical lymphadenopathy (Figure 2): due to metastasis to the lymphatic system.

- Wheeze on auscultation: due to the tumour obstructing an airway.

When to refer urgently

Patients presenting with “red-flag” symptoms must be referred on a “2-week wait”. This means that the patient must be seen by a hospital specialist within 2 weeks of the hospital receiving the referral form. The patient should also have a chest X-ray within 2 weeks.

The NICE criteria for a 2-week wait referral for lung cancer are:

- Chest X-ray findings suggestive of lung cancer, or

- Over 40 years old and unexplained haemoptysis16

Other patients may just need an urgent chest x-ray (within 2 weeks) before a decision to refer on a 2-week wait is made. These patients must be over 40 years old, and have two of the following unexplained symptoms (one if they have ever smoked):

- Cough

- Weight loss

- Appetite loss

- Dyspnoea

- Chest pain

- Fatigue17

Differential diagnosis

Unexplained cough and weight loss have important differential diagnoses. Table 2 outlines these differential diagnoses, and the features which differentiate them from lung cancer.

Table 2 Differential diagnoses of lung cancer

| Differential diagnosis | Features differentiating from lung cancer |

| Tuberculosis | Drenching night sweats

Positive sputum culture and microscopy Chest X-ray: cavitating lesion/hilar lymphadenopathy |

| Metastasis to the lungs from other sites | Symptoms relevant to the primary tumour (e.g. haematuria due to renal cell carcinoma)

CT head-abdomen-pelvis: shows primary tumour FDG-PET: increased uptake at the primary tumour site |

| Sarcoidosis | Enlarged parotids

Skin signs: erythema nodosum and lupus pernio Tissue biopsy: non-caseating granulomas |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s disease) | Saddle-nose deformity

Positive cANCA Urinalysis: haematuria, proteinuria, red cell casts |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Drenching night sweats

Hepatosplenomegaly Positive lymph node biopsy (anti-CD20 stain) |

Investigations

Bedside investigations

- Pulse oximetry: aim for 94-98% (88-92% if the patient also has COPD – see the Geeky Medics guide on COPD).

- ECG: always performed pre-operatively.

Laboratory investigations

- FBC: may show anaemia.

- LFTs: raised ALP and GGT may indicate hepatic metastases, raised ALP may indicate bone metastases.

- U&E: in order to know the patient’s baseline before treatment. Hyponatraemia may be due to syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), which is more common in small cell carcinoma.

- Serum calcium: elevated with the secretion of PTH-related protein (PTHrP), which is more common in squamous cell carcinoma.

Imaging

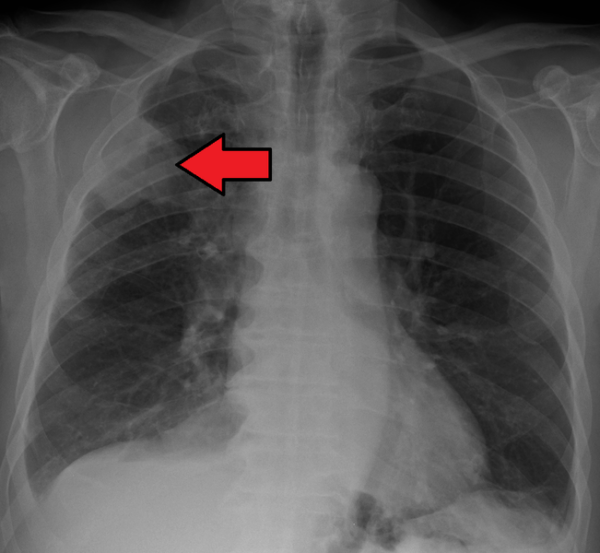

- Chest X-ray (figure 3): first-line investigation in suspected lung cancer. May show single or multiple opacities, pleural effusion and/or lung collapse.

- CT chest-abdomen-pelvis (figure 4): used to confirm chest X-ray findings. Consider CT if lung cancer is suspected despite a negative chest X-ray. CT of abdomen and pelvis assesses for metastases.

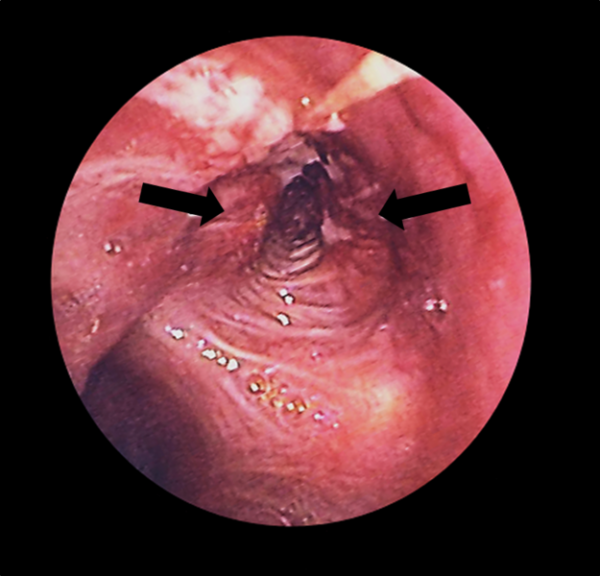

- Bronchoscopy and biopsy (figure 5): bronchoscopy involves the insertion of a small camera into the airways to directly visualise the tumour. A biopsy of the tumour is taken, and then a pathologist confirms the presence of malignant cells, the lung cancer subtype (e.g. adenocarcinoma) and the presence of targetable mutations (e.g. EGFR mutation – see the management section). A biopsy is essential in order to make the diagnosis of lung cancer.

- Positron emission tomography CT (PET-CT): enables staging of lung cancer (see table 3).

Staging of lung cancer

This is a summarised version of the staging criteria; any more detail is beyond the scope of undergraduate learning. Note that the TNM staging classification is first used, and then converted to the I-IV staging system which is used to guide management decisions.

Table 3 Lung cancer staging.21

| Stage | Description |

| I | One small tumour (<4cm) – localised to one lung |

| II | Larger tumour (>4cm) – may have spread to nearby lymph nodes |

| III | Tumour that has spread to contralateral lymph nodes, or grown into nearby structures (e.g. trachea) |

| IV | Tumour that has spread to lymph nodes outside the chest, or other organs (e.g. liver) |

Management

Non-small cell lung cancer

Stage I – III

- Surgery: options include lobectomy/pneumonectomy in patients with intact lung function, or wedge resection in patients with reduced lung function (e.g. elderly, underlying respiratory conditions).

- Pre-operative chemotherapy

- Post-operative chemotherapy and radiotherapy: may not be needed in some cases of stage I lung cancer.

If unsuitable for surgery (e.g. too frail), patients may be offered stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). Compared to conventional radiotherapy, SABR involves directing a more intense and focused beam of radiation at the tumour. This reduces the number of radiotherapy sessions needed and minimises damage to surrounding tissue.22

Stage IV

- Targeted therapy: these drugs target mutations which drive the pathogenesis of lung cancer (Table 3). Medical students should be aware that these targeted therapies exist and are used for stage IV lung cancer, but do not need to know much more detail than this.

- Immunotherapy: these drugs target immune checkpoints, which prevent the patient’s immune cells from killing tumour cells. For example, the immune checkpoint PD-L1 is targeted by pembrolizumab. Immunotherapy is an emerging field in cancer management.

- Chemotherapy: especially important for patients who do not have any mutations which can be targeted by targeted therapies.

- Palliative care: includes palliative radiotherapy, for metastases and symptom control.

Table 3 Examples of targeted therapy for non-small cell lung cancer

| Mutation | Drug |

| EGFR | Gefitinib

Osimertinib |

| ALK | Alectinib |

| ROS1 | Crizotinib |

Small cell lung cancer

- Chemotherapy and radiotherapy

- Surgery: rare in small cell lung cancer, as most patients present with advanced disease.

- Prophylactic cranial irradiation: since small cell lung cancer is associated with a high risk of brain metastases, radiotherapy is directed at the brain to prevent brain metastases.

Complications

Disease-related complications

- Horner’s syndrome (figure 6): due to a Pancoast tumour in the lung apex infiltrating the brachial plexus. Features include ptosis, miosis, anhidrosis (reduced sweating) and enophthalmos (posterior displacement of the eyeball into the orbit). This is a common exam question!

- Superior vena cava obstruction (figure 7 and 8): tumour compresses the superior vena cava, preventing venous drainage from the head and neck, leading to facial swelling and distended neck/chest veins.

- Paraneoplastic syndromes: such as SIADH and Lambert-Eaton syndrome.

Treatment-related complications

- Due to chemotherapy: alopecia, neutropaenia, bone marrow toxicity.

- Due to radiotherapy: mucositis, pneumonitis, oesophagitis.

Key points

- Lung cancer is split into non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer.

- The main risk factor for lung cancer is tobacco smoking.

- Lung cancer classically presents with unexplained cough and weight loss, but some patients may present with non-specific symptoms (such as fatigue).

- Diagnosis is based on imaging (chest X-ray and CT) and biopsy.

- Management of non-small cell lung cancer is surgery in early disease and chemotherapy ± targeted therapy in advanced disease. Chemoradiation is the mainstay of management for small cell lung cancer.

- Complications of lung cancer include Horner’s syndrome, superior vena cava obstruction and paraneoplastic syndromes.

Feedback

Please click here to fill out the feedback form, which should take less than 1 minute of your time. Feedback is vital as it allows authors to improve their articles, leading to even better content on Geeky Medics!

References

- Bray F et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2018. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Lung and Pleural Cancers – Recognition and Referral. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Office for National Statistics. Cancer Survival in England. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Zappa C and Mousa SA. Non-small cell lung cancer: current treatment and future advances. Translational Lung Cancer Research. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Zappa C and Mousa SA. Non-small cell lung cancer: current treatment and future advances. Translational Lung Cancer Research. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Malhotra J et al. Risk factors for lung cancer worldwide. European Respiratory Journal. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Nitadori J et al. Association between lung cancer incidence and family history of lung cancer. Chest. Published in 2006. Available from: [LINK]

- BMJ Best Practice. Non-small cell lung cancer. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Popper HH. Progression and metastasis of lung cancer. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Ellis PM and Vandermeer R. Delays in the diagnosis of lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Disease. Published in 2011. Available from: [LINK]

- Besaratinia A and Pfeifer GP. Second-hand smoke and human lung cancer. Lancet Oncology. Published in 2009. Available from: [LINK]

- Tisdale MJ. Mechanisms of cancer cachexia. Physiological Reviews. Published in 2009. Available from: [LINK]

- Sarkar M et al. Digital Clubbing. Lung India. Published in 2012. Available from: [LINK]

- D Desherinka. Finger clubbing. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- I Furst. Cervical lymphadenopathy. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. Published in 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. Published in 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- J Heilman. Chest X-Ray. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- CT Chest. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- J Heuser. Bronchoscopy. [CC BY]. Available from: [LINK]

- Amin MB. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (8th Edition). Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Chang JY. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy: aim for a cure of cancer. Annals of Translational Medicine. Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- A Nautiyal. Horner’s Syndrome. [CC BY]. Available from: [LINK]

- H Fred and H Van Dijk. Superior Vena Cava Obstruction. [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

Reviewer

Dr Neeraj Shah

Respiratory Medicine Registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies