- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Upper limb neurological examination frequently appears in OSCEs and you’ll be expected to identify the relevant clinical signs using your examination skills. This upper limb neurological examination OSCE guide provides a clear step-by-step approach to examining the neurology of the upper limbs, with an included video demonstration.

Upper vs lower motor neuron lesions

The main purpose of a neurological examination is to localise where in the nervous system the problem is. This can seem daunting, but with practice, it is relatively straightforward. The most basic localisation question you have to think about during the upper and lower limb examination is:

- Is there an upper (i.e. brain or spinal cord) or lower (i.e. nerve roots, peripheral nerve, neuromuscular junction or muscle) motor neuron lesion?

The table below provides a summary of key upper motor neuron (UMN) and lower motor neuron (LMN) signs you may identify in an upper limb neurological examination.

| UMN signs | LMN signs | |

| Inspection | No fasciculation or significant wasting (there may however be some disuse atrophy or contractures) | Wasting and fasciculation of muscles |

| Pronator drift | May be present | There may be some drift/movement of the arm(s) if weak or deafferented, but not pronator drift |

| Tone | Increased (spasticity or rigidity) | Decreased (hypotonia) or normal |

| Power | Classically a “pyramidal” pattern of weakness (extensors weaker than flexors in arms, and vice versa in legs) | Different patterns of weakness, depending on the cause (e.g. classically a proximal weakness in muscle disease, a distal weakness in peripheral neuropathy) |

| Reflexes | Exaggerated or brisk (hyperreflexia) | Reduced or absent (hyporeflexia or areflexia) |

Gather equipment

Gather the appropriate equipment:

- Tendon hammer

- Neurotip

- Cotton wool

- Tuning fork (128Hz)

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language.

Gain consent to proceed with the examination.

Adequately expose the patient’s arms for the examination from the shoulders to the hands.

Position the patient appropriately (either sitting on the side of the examination couch or lying at 45°).

Ask the patient if they have any pain before proceeding with the clinical examination.

General inspection

Clinical signs

Perform a brief general inspection of the patient, looking for clinical signs suggestive of underlying pathology:

- Scars: may provide clues regarding previous spinal, axillary or upper limb surgery.

- Wasting of muscles: suggestive of lower motor neuron lesions or disuse atrophy.

- Tremor: there are several subtypes including resting tremor and intention tremor.

- Fasciculations: small, local, involuntary muscle contraction and relaxation which may be visible under the skin. Associated with lower motor neuron pathology (e.g. amyotrophic lateral sclerosis).

- Pseudoathetosis: abnormal writhing movements (typically affecting the fingers) caused by a failure of proprioception.

- Chorea: brief, semi-directed, irregular movements that are not repetitive or rhythmic but appear to flow from one muscle to the next. Patients with Huntington’s disease typically present with chorea.

- Myoclonus: brief, involuntary, irregular twitching of a muscle or group of muscles. All individuals experience benign myoclonus on occasion (e.g. whilst falling asleep) however persistent widespread myoclonus is associated with several specific forms of epilepsy (e.g. juvenile myoclonic epilepsy).

- Tardive dyskinesia: involuntary, repetitive body movements which can include protrusion of the tongue, lip-smacking and grimacing. This condition can develop secondary to treatment with neuroleptic medications including antipsychotics and antiemetics.

- Hypomimia: a reduced degree of facial expression associated with Parkinson’s disease.

- Ptosis and frontal balding: typically associated with myotonic dystrophy.

- Ophthalmoplegia: weakness or paralysis of one or more extraocular muscles responsible for eye movements. Ophthalmoplegia can be caused by a wide range of neurological disorders including multiple sclerosis and myasthenia gravis.

Objects or equipment

Look for objects or equipment on or around the patient that may provide useful insights into their medical history and current clinical status:

- Walking aids: the ability to walk can be impacted by a wide range of neurological pathology.

- Prescriptions: prescribing charts or personal prescriptions can provide useful information about the patient’s recent medications.

Pronator drift

Assessment

Checking for pronator drift is a useful way of assessing for mild upper limb weakness and spasticity:

1. Ask the patient to hold their arms out in front of them with their palms facing upwards and observe for signs of pronation for 20-30 seconds.

2. If no pronation occurs, ask the patient to close their eyes and observe once again for pronation (this typically accentuates the effect due to the reliance on proprioception alone).

Interpretation

Pronator drift involves both pronation (rotation of the forearm/wrist from palm up towards a palm down position) and downward movement of an upper limb (i.e. drift). The presence of pronator drift indicates a contralateral corticospinal tract lesion. Pronation occurs because, in the context of an UMN lesion, the supinator muscles of the forearm are typically weaker than the pronator muscles.

Tone

Tone

Assessment

Assess tone in the muscle groups of the shoulder, elbow and wrist on each arm, comparing each side as you go:

1. Support the patient’s arm by holding their hand and elbow.

2. Ask the patient to relax and allow you to fully control the movement of their arm.

3. Move the muscle groups of the shoulder (circumduction), elbow (flexion/extension) and wrist (circumduction) through their full range of movements.

4. Feel for abnormalities of tone as you assess each joint (e.g. spasticity, rigidity, cogwheeling, hypotonia).

Spasticity vs rigidity

Spasticity is associated with pyramidal tract lesions (e.g. stroke) and rigidity is associated with extrapyramidal tract lesions (e.g. Parkinson’s disease). Spasticity and rigidity both involve increased tone, so it’s important to understand how to differentiate them clinically.

Spasticity is “velocity-dependent”, meaning the faster you move the limb, the worse it is. There is typically increased tone in the initial part of the movement which then suddenly reduces past a certain point (known as “clasp knife spasticity”). Spasticity is also typically accompanied by weakness.

Rigidity is “velocity independent” meaning it feels the same if you move the limb rapidly or slowly. There are two main sub-types of rigidity:

- Cogwheel rigidity involves a tremor superimposed on the hypertonia, resulting in intermittent increases in tone during movement of the limb. This subtype of rigidity is associated with Parkinson’s disease.

- Lead pipe rigidity involves uniformly increased tone throughout the movement of the muscle. This subtype of rigidity is typically associated with neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Power

Assess the power of the patient’s upper limbs by working through the sequence of assessments below.

You must stabilise and isolate the relevant joint for each assessment to ensure you can accurately measure and compare muscle strength. As a result, you should only assess one side at a time.

At each stage in the assessment, you should compare like for like.

Use the MRC muscle power assessment scale for scoring muscle strength (details below).

You need to communicate clear instructions to the patient during each stage of the assessment. Demonstrating each position you want the patient to assume can aid understanding.

See our rapid screen table at the end of the guide for a quick way to assess the nerves of the upper limb.

Shoulder

Shoulder ABduction

Myotome assessed: C5 (axillary nerve)

Muscles assessed: deltoid (primary) and other shoulder abductors

Instructions:

1. Ask the patient to flex their elbows and ABduct their shoulders to 90°: “Bend your elbows and bring your arms out to the sides like a chicken.”

2. Apply downward resistance on the lateral side of the upper arm whilst asking the patient to maintain their arm’s position: “Don’t let me push your shoulder down.”

Shoulder ADduction

Myotomes assessed: C6/7 (thoracodorsal nerve)

Muscles assessed: teres major, latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major

Instructions:

1. Ask the patient to ADduct their shoulders to 45° bringing their elbows closer to their body: “Now bring your elbows a little closer to your sides.”

2. Apply upward resistance on the medial side of the upper arm whilst asking the patient to maintain their arm’s position: “Don’t let me pull your arms away from your sides.”

Elbow

Elbow flexion

Myotomes assessed: C5/6 (musculocutaneous and radial nerve)

Muscles assessed: biceps brachii, coracobrachialis and brachialis

Instructions:

1. Ask the patient to flex their elbow: “Put your hands up like a boxer.”

2. Apply resistance by pulling the forearm whilst stabilising the shoulder joint: “Don’t let me pull your arm away from you.”

Elbow extension

Myotome assessed: C7 (radial nerve)

Muscles assessed: triceps brachii

Instructions: With the patient’s elbows still in the flexed position, apply resistance by pushing the forearm towards the patient whilst stabilising the shoulder joint: “Don’t let me push your arm towards you.”

Wrist

Wrist extension

Myotome assessed: C6 (radial nerve)

Muscles assessed: extensors of the wrist

Instructions:

1. Ask the patient to hold their arms out in front of them with their palms facing downwards: “Hold your arms out in front of you, with your palms facing the ground.”

2. Ask the patient to make a fist and extend their wrist joints, keeping their wrists in this position whilst you apply resistance: “Make a fist, cock your wrists back and don’t let me pull them downwards.”

Wrist flexion

Myotomes assessed: C6/7 (median and ulnar nerve)

Muscles assessed: flexors of the wrist

Instructions: With the patient still holding their arms out in front of them, now ask them to flex their wrist joints and keep them in this position whilst you apply resistance: “Ok now point your wrists downwards and don’t let me pull them up.”

Fingers

Finger extension

Myotome assessed: C7 (radial nerve)

Muscles assessed: extensor digitorum

Instructions: Ask the patient to hold their fingers out straight whilst you apply downwards resistance: “Hold your fingers out straight and don’t let me push them down.”

Finger ABduction

Myotome assessed: T1 (ulnar nerve)

Muscles assessed:

- First dorsal interosseous (FDI)

- Abductor digiti minimi (ADM)

Instructions: Ask the patient to abduct their fingers against resistance. You should assess abduction in FDI and ADM separately using the equivalent finger of your own to apply resistance: “Splay your fingers outwards and don’t let me push them together.”

Thumb ABduction

Myotomes assessed: T1 (median nerve)

Muscle assessed: abductor pollicis brevis

Instructions: Ask the patient to turn their hand over so their palm is facing upwards and to position their thumb over the midline of the palm. Advise them to keep it in this position whilst you apply downward resistance with your own thumb: “Point your thumbs to the ceiling and don’t let me push them down.”

Patterns of muscle weakness

Upper motor neuron lesions cause a ‘pyramidal’ pattern of weakness that disproportionately affects upper limb extensors and lower limb flexors (i.e. upper limb extensors are weaker than flexors in an upper limb neurological assessment).

Lower motor neuron lesions cause a focal pattern of weakness, with only the muscles directly innervated by the damaged neurones affected.

MRC muscle power assessment scale

The MRC scale of muscle strength uses a score of 0 to 5 to grade the power of a particular muscle group in relation to the movement of a single joint.

| Score | Description |

| 0 | No contraction |

| 1 | Flicker or trace of contraction |

| 2 | Active movement, with gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Active movement against gravity |

| 4 | Active movement against gravity and resistance |

| 5 | Normal power |

Reflexes

Explain to the patient that you are now going to assess their reflexes by tapping gently on their arm with a tendon hammer (it is useful to show the patient the tendon hammer at this stage).

For each of the reflexes, the patient’s upper limb needs to be completely relaxed.

Make sure to hold the tendon hammer handle at its end to allow gravity to aid a good swing.

If a reflex appears absent make sure the patient is fully relaxed and then perform a reinforcement manoeuvre by asking the patient to clench their teeth together whilst you simultaneously tap the tendon.

Biceps reflex (C5/6)

1. With the patient’s arm relaxed, locate the biceps brachii tendon which is typically found at the medial aspect of the antecubital fossa.

2. Place the thumb of your non-dominant hand over the tendon and then tap your thumb with the tendon hammer.

3. Observe for a contraction of the biceps muscle and associated flexion of the elbow.

Supinator (brachioradialis) reflex (C5/6)

1. Locate the brachioradialis tendon which can be found on the posterolateral aspect of the wrist approximately 4 inches proximal to the base of the thumb.

2. With two fingers positioned over the tendon, tap your fingers with the tendon hammer.

3. Observe for a contraction of the brachioradialis muscle and associated flexion, pronation or supination of the forearm at the elbow.

Triceps reflex (C7)

1. Position the patient’s arm so that the triceps tendon is relaxed: this is commonly achieved by resting the patient’s elbow in 90º flexion on their lap or by supporting the patient’s forearm.

2. Locate the triceps tendon, which can be found superior to the olecranon process of the ulna.

3. Tap the tendon with the tendon hammer and observe for a contraction of the triceps muscle.

Hyperreflexia vs hyporeflexia

Hyperreflexia is typically associated with upper motor neuron lesions (e.g. stroke, spinal cord injury) due to the loss of inhibition from higher brain centres which normally exert a degree of suppression over the lower motor neuron reflex arc.

Hyporeflexia is typically associated with lower motor neuron lesions (e.g. brachial plexus pathology or other peripheral nerve injuries) due to loss of the efferent and afferent branches of the normal reflex arc.

In cerebellar disease, reflexes are described as ‘pendular’, which means less brisk and slower in their rise and fall. This sign is, however, very subjective and often reflexes appear to be ‘normal’ in cerebellar disease.

Sensation

It’s easy to get bogged down in examining sensation, but the key points are as follows:

- Check at least one modality each from the dorsal columns and spinothalamic tracts.

- Ensure the patient has their eyes closed for the assessment.

- Demonstrate normal sensation on the patient’s sternum.

- Assess sensation across each of the upper limb dermatomes (see below), comparing left to right at equivalent regions as you progress.

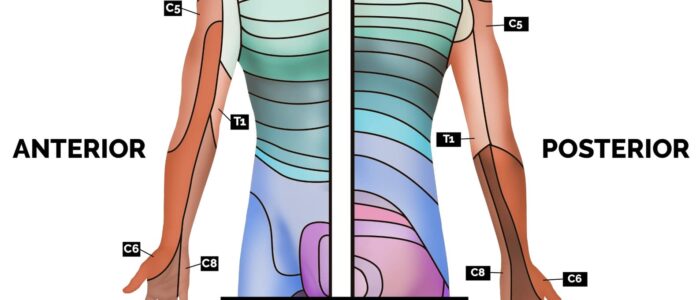

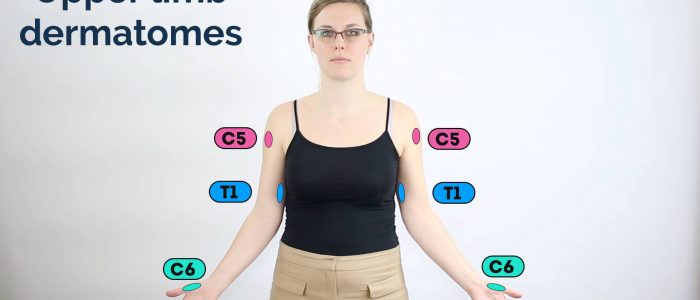

Dermatomes

It’s important to avoid assessing sensation close to dermatomal boundaries to minimise the risk of misinterpretation. Here are some locations you can use to assess each of the upper limb dermatomes:

- C5: the lateral aspect of the lower edge of the deltoid muscle (known as the “regimental badge”).

- C6: the palmar side of the thumb.

- C7: the palmar side of the middle finger.

- C8: the palmar side of the little finger.

- T1: the medial aspect antecubital fossa, proximal to the medial epicondyle of the humerus.

Light touch sensation

Light touch sensation involves both the dorsal columns and spinothalamic tracts.

1. Ask the patient to close their eyes and touch their sternum with the wisp of cotton wool to provide an example of light touch sensation.

2. Ask the patient to say “yes” when they feel the sensation.

3. Using the wisp of cotton wool, begin to assess light touch sensation across each of the upper limb dermatomes, comparing each side as you go by asking the patient if it feels the same.

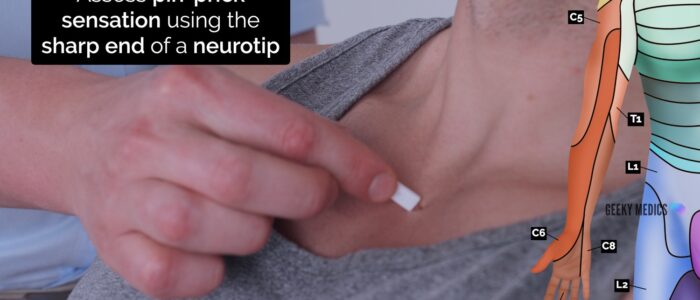

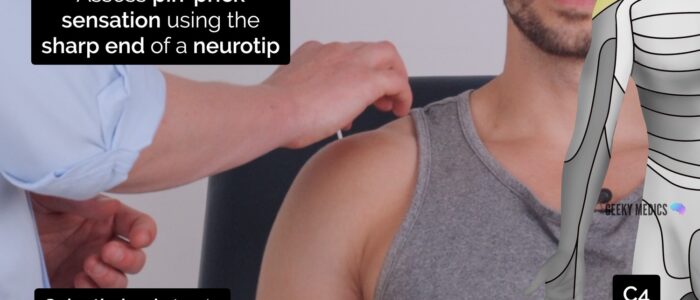

Pin-prick sensation

Pin-prick (pain) sensation involves the spinothalamic tracts.

Repeat the previous assessment steps used for light touch sensation, but this time using the sharp end of a neuro-tip.

If loss of sensation is noted distally, test for “glove” distribution of sensory loss (associated with peripheral neuropathy) by moving distal to proximal.

Vibration sensation

Vibration sensation involves the dorsal columns.

1. Ask the patient to close their eyes and to let you know both when they can detect vibration and when it stops.

2. Tap a 128 Hz tuning fork and place onto the patient’s sternum to check they are able to feel it vibrating. Then grasp the ends of the tuning fork to cease vibration and see if the patient is able to accurately identify that it has stopped.

3. Tap the tuning fork again and place onto the interphalangeal joint of the patient’s thumb. If the patient is able to accurately identify when the vibration begins and when it stops at this point in both upper limbs, the assessment is complete.

4. If vibration sensation is impaired at the interphalangeal joint of the patient’s thumb, continue to sequentially assess more proximal joints (e.g. carpometacarpal joint of the thumb → elbow joint → shoulder joint) until the patient is able to accurately identify vibration.

Joint proprioception

Joint proprioception, also known as joint position sense, involves the dorsal columns.

1. Begin assessment of joint proprioception at the interphalangeal joint of the thumb by holding the distal phalanx of the thumb by its sides (avoid holding the nail bed as this can allow the patient to determine direction based on pressure).

2. Demonstrate movement of the thumb “upwards” and “downwards” to the patient whilst they watch.

3. Ask the patient to close their eyes and state if you are moving their thumb up or down.

4. Move the thumb up or down 3-4 times in a random sequence to see if the patient is able to accurately identify joint position with their eyes closed.

5. If the patient is unable to correctly identify the direction of movement, continue to sequentially assess more proximal joints (e.g. carpometacarpal joint of the thumb → wrist → elbow → shoulder).

Patterns of sensory loss

Mononeuropathies result in a localised sensory disturbance in the area supplied by the damaged nerve.

Peripheral neuropathy typically causes symmetrical sensory deficits in a ‘glove and stocking’ distribution in the peripheral limbs. The most common causes of peripheral neuropathy are diabetes mellitus and chronic alcohol excess.

Radiculopathy occurs due to nerve root damage (e.g. compression by a herniated intervertebral disc), resulting in sensory disturbances in the associated dermatomes.

Spinal cord damage results in sensory loss both at and below the level of involvement in a dermatomal pattern due to its impact on the sensory tracts running through the cord.

Thalamic lesions (e.g. stroke) result in contralateral sensory loss.

Myopathies often involve symmetrical proximal muscle weakness.

Coordination

Finger-to-nose test

Assessment

The finger-to-nose test is a convenient method of assessing upper limb co-ordination:

1. Position your finger so that the patient has to fully outstretch their arm to reach it.

2. Ask the patient to touch their nose with the tip of their index finger and then touch your fingertip.

3. Ask the patient to continue to do this finger to nose motion as fast as they are able to.

Interpretation

When patients with cerebellar pathology perform this task they may exhibit both dysmetria and intention tremor:

- Dysmetria: refers to a lack of coordination of movement. Clinically this results in the patient missing the target by over/undershooting.

- Intention tremor: a broad, coarse, low-frequency tremor that develops as a limb reaches the endpoint of a deliberate movement. Clinically this results in a tremor that becomes apparent as the patient’s finger approaches yours. Be careful not to mistake an action tremor (which occurs throughout the movement) for an intention tremor.

The presence of dysmetria and intention tremor is suggestive of ipsilateral cerebellar pathology.

Dysdiadochokinesia

Dysdiadochokinesia is a term that describes the inability to perform rapid, alternating movements, which is a feature of ipsilateral cerebellar pathology.

Assessment

1. Ask the patient to place their left palm on top of their right palm.

2. Then ask them to turn over their left hand and touch the back of it onto their right palm.

3. Now ask them to return their left hand to the original position (left palm on right palm).

4. Ask the patient to now repeat this sequence of movements as fast as they are able until you tell them to stop. It is often useful to demonstrate the sequence of movements to the patient to aid understanding.

5. Observe the speed and fluency by which the patient is able to carry out this sequence of rapidly alternating movements.

6. Repeat the assessment with the other hand.

Interpretation

Patients with cerebellar ataxia may struggle to carry out this task, with their movements appearing slow and irregular. The presence of dysdiadochokinesia suggests ipsilateral cerebellar pathology.

To complete the examination…

Explain to the patient that the examination is now finished.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Summarise your findings.

Example summary

“Today I examined Mr Smith, a 32-year-old male. On general inspection, the patient appeared comfortable at rest, with normal speech and no other stigmata of neurological disease. There were no objects or medical equipment around the bed of relevance.”

“Assessment of the upper limbs revealed normal tone, power, reflexes, sensation and coordination.”

“In summary, these findings are consistent with a normal upper limb neurological examination.”

“For completeness, I would like to perform the following further assessments and investigations.”

Further assessments and investigations

- Full neurological examination including the cranial nerves, lower limbs and cerebellar assessment.

- Neuroimaging (e.g. MRI spine and head).

Rapid screen table

| Nerve (root) | Example muscle | Action | Sensation | Reflex |

| Axillary (C5) | Deltoid | Shoulder ABduction | Lateral aspect of the lower edge of the deltoid muscle | – |

| Musculocutaneous (C5-C6) | Biceps | Elbow flexion | Palmar side of the thumb | Biceps |

| Radial (C7) | Extensors (extensor carpi radialis/ulnaris and digitorum) | Wrist/finger extension | Palmar side of the middle finger | Triceps |

| Ulnar (T1) | First dorsal interosseus (FDI) | Index finger ABduction | Palmar side of the little finger | – |

| Median (T1) | Abductor pollicis brevis (APB) | Thumb ABduction | Medial aspect of the inferior portion of the upper arm, superior to the elbow joint | – |

Reviewer

Dr David Bargiela

Neurologist