- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a non-enveloped double-stranded circular DNA virus in the Papillomaviridae family. There are over 150 types of HPV, 40 of which affect the anogenital area and 15 of which are oncogenic.1

Important low-risk types include HPV-6 and HPV-11, which cause genital warts, the most common viral sexually transmitted infection (STI).1

Worldwide, high-risk HPV causes around 5% of cancers, affecting the cervix, vulva, vagina, anus, penis, head, and neck.2

This article will focus on the mechanism of HPV infection, and the pathophysiology, clinical features, and management of genital warts. For more information on the closely linked cervical cancer and anal cancer, please read their respective articles.

Epidemiology

HPV is extremely prevalent. Nearly all sexually active men and women acquire HPV infection during their lifetime, and almost 40% of women are infected with HPV within the first two years of sexual activity.3,4

All HPV types can cause proliferative lesions, however, the most prevalent types are classified as high-risk if they can cause malignant neoplasms, and low-risk if they can cause benign lesions, such as genital warts.

Low-risk HPV-6 and HPV-11 are the most common causes of genital warts, which is the most common viral STI diagnosed in sexual health clinics in the UK and worldwide. In 2019, there were 50,700 diagnoses of the first episode of genital warts. This was almost halved to 27, 473 in 2020; this decline is thought to be related to the expanded HPV vaccine programme and the reduction in face-to-face consultations owing to the COVID-19 pandemic.5

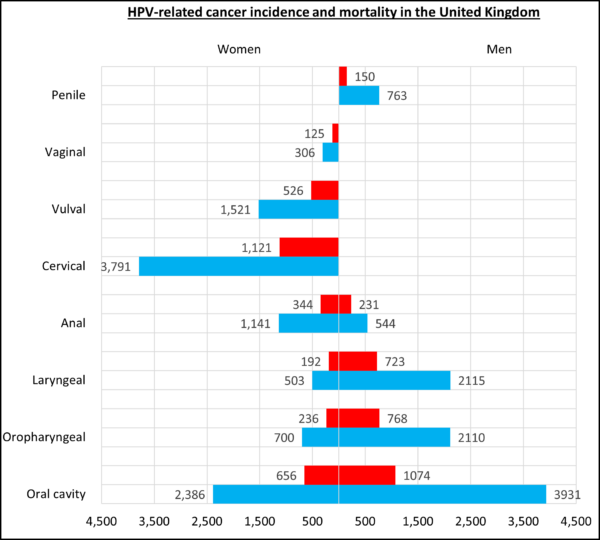

High-risk HPV causes around 5% of cancers worldwide and the prevalence of high-risk HPV in the UK is 16%, including the most common type- HPV-16 (12%).6 Through the mechanisms described below, HPV can cause cancer of the cervix, vulva, vagina, anus, penis, head, and neck (Figure 1).

Aetiology

HPV belongs to the Papillomaviridae family and includes over 200 different types which are grouped according to their genome. Although all HPV types can cause proliferative lesions, the most prevalent types are classified as high-risk or low-risk according to their risk of causing malignant neoplasms or benign lesions, such as genital warts.

Important high-risk types include HPV-16 and HPV-18, which contribute to over 70% of cervical cancer, and 31, 33, 35, 45, 52 and 58, which account for an additional 20% of cervical cancers. Low-risk HPV capable of causing genital warts include HPV-6 and HPV-11.1

HPV life cycle

Microtrauma to the epithelial cells of the skin, oral and genital mucosa provides the virus access to basal keratinocytes. HPV uses its L1 and L2 capsid proteins to bind and enter the cell via endocytosis.1

The undifferentiated basal layer acts as a reservoir, proliferating symmetrically to form more basal cells, wherein HPV establishes a persistent infection, or asymmetrically, whereby one daughter cell moves up through epithelium. As these infected basal cells differentiate into epithelial cells, the virus begins expressing its early (E) genes, allowing it to replicate and produce new virions to be released from the differentiated epithelial cell surface. 7

The majority (70-90%) of HPV infections are asymptomatic and are cleared within 12-14 months by the immune system via a Th1 pro-inflammatory and cell-mediated response.1

This immune response may be sufficient to completely clear the viral infection or to keep the virus in very low copy numbers which avoid detection. However, only 70-80% of genital HPV infection results in antibody production, which is insufficient to control for new infections.1

Pathophysiology and carcinogenesis

HPV employs several strategies to induce hyperproliferation of the infected epithelia, resulting in warts:8

- Genital warts: verrucous papules in the anogenital area

- Common warts: rough, raised bumps commonly on the hands and fingers

- Plantar warts (verrucas): hard, grainy growth commonly on the heels or balls of feet

- Flat warts: flat-topped, raised lesions commonly on the face

High-risk HPV types can remain intraepithelial by proliferating through the undifferentiated layer of cells, thereby avoiding the host immune response. These oncogenic types demonstrate increased activity of viral E6 and E7 oncoproteins, which respectively inhibit p53 and pRb tumour suppressor genes. This results in cell cycle dysregulation, uncontrolled cellular proliferation and the accumulation of mutations that can lead to invasive malignancy.1

Transmission9

HPV most commonly spreads through direct skin-skin contact during sexual intercourse.

Other routes of transmission include:

- Contact with contaminated surfaces or objects

- Oro-genital transmission

- Perinatal vertical transmission

- Autoinoculation

Risk factors

Factors increasing the risk of HPV include:

- Early age of first sexual intercourse

- A high number of sexual partners

- Condomless sex

- Immunosuppression (including HIV)

Clinical features

History

Most HPV infections (70-90%), are asymptomatic and are cleared within 12-14 months by the immune system.

Warts tend to present as single or multiple 2-5mm cauliflower-like growths. On non-hairy skin, these tend to be soft and non-keratinised, whereas, on hairy skin, these tend to be firm and keratinised.

Warts may be associated with the following symptoms:

- Pruritus and irritation

- Pain and bleeding due to local trauma

- Haematuria and distortion of urinary flow due to intra-meatal warts

A full sexual history should be taken to assess relevant risk factors. This should include HPV vaccination history, sexual activity, number of sexual partners, use of barrier contraception, and symptoms suggesting co-infection with a sexually transmitted infection.

Clinical examination

It is important to examine the anogenital area, including the external genitalia, perineum, and anus to visually confirm the diagnosis and determine the extent of the lesions. Other examinations required may include:

- Vaginal speculum examination

- Meatoscopy for intra-meatal warts

- Proctoscopy for warts at the anal margin

- Anoscopy is recommended in patients with recurrent perianal warts

Differential diagnoses

Table 1. Differential diagnoses to consider in the context of anogenital lesions.

|

Differential diagnosis |

Clinical summary |

|

Condyloma latum |

Moist whiteish papules which may secrete fluid Highly contagious manifestation of secondary syphilis Systemic symptoms may include fever, malaise, weight loss |

|

Molluscum contagiosum |

Fleshy or pearl-coloured lesions with central dells (Figure 5) Caused by the molluscum contagiosum virus (Poxvirus) |

|

Pearly penile papules |

1-2mm flesh-coloured papules around the corona or sulcus of the penis glans (Figure 6) Asymptomatic, normal anatomical variant |

|

Skin tags |

Soft, skin-coloured or tan-brown, round/oval, pedunculated papilloma Usually found on the neck, armpits, around the groin or under breasts |

|

Carcinoma in situ |

Multifocal, erythematous or pigmented lesions Usually have a smooth and velvety surface |

Investigations

Genital warts are diagnosed following clinical examination. Swabs and blood tests are not routinely performed. However, it is important to offer a full sexual health screen.

At the bedside, this may include a urine sample and swabs of the vagina, cervix, rectum and oropharynx for NAAT (chlamydia, gonorrhoea). Laboratory investigations may include full blood count, CRP and serology (HIV, syphilis, HBV, HCV).

Biopsy could be considered if the wart is indurated, fixed, bleeding, ulcerated or pigmented.9

Management

Although there is no specific treatment for HPV infection, treatments are available that aim to destroy or remove warts and lesions. However, in around 20% of people, warts disappear within 6 months and require no treatment.

Treatment should be led by a sexual health specialist but can be performed in primary care. Options should be discussed and the patient’s preference for self-administration should be considered.

Self-administered treatment includes topical treatment with podophyllotoxin, imiquimod and sinecathins. Those receiving these treatments should be advised of potential side effects, including potential skin irritation for themselves and any sexual partner. Imiquimod and sinecatechins can also weaken condoms and make them less effective. Specialists may treat with trichloroacetic acid, or use ablative methods such as cryotherapy, excision or electrocautery.

Patient advice

All patients should be counselled regarding smoking cessation and using barrier methods of contraception. Consider suggesting that sexual partners may benefit from assessment for undetected genital warts and other STIs.

Patients may require reassurance that due to the long latency of HPV (3 weeks – 8 months), a recent diagnosis does not always imply partner infidelity.

Prevention

Protective factors against HPV infection include condom usage, male circumcision, limiting the number of sexual partners and vaccination.

Vaccination15,16

HPV vaccines contain particles from the major protein of the viral capsid. There have been several changes to the vaccination schedule, but currently, the following groups are eligible:

- Girls and boys aged 11-14: 2 doses, one given 6-24 months after the first

- Individuals aged 15-25 who did not receive it: 2 doses, 6 months apart

- Men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM) aged 15-45: 2 doses, 6 months apart

- High-risk individuals (transgender, sex workers): 2 doses, 6 months apart

- People living with HIV (PLWH): 3 doses, all within 24 months

In 2008, the bivalent vaccine against HPV 16 and 18 was introduced in the national immunisation programme, however, this was replaced in 2012 by the quadrivalent vaccine Gardasil (against HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18). This is planned to be replaced again in 2022 by the 9-valent vaccine Gardasil 9 (against HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58) to offer more protection against cancer and genital warts.

The programme was initially aimed to provide protection for young girls before the onset of sexual activity but was expanded in 2019 to include boys. As of 2020, there is 85% coverage for girls and 53% for boys.

For individuals aged 15-25 who did not receive the vaccine, MSM aged 15-45 and high-risk groups between the ages of 15-25 are eligible for the vaccine, a schedule of 3 doses within 12 months was recommended, however from April 2022, has changed to 2 doses, 6 months apart.

Complications

The main complications result from anxiety and distress relating to the appearance of warts.

Topical treatments may result in persistent hypo- or hyper-pigmentation and hypertrophic scarring.

Prognosis

In around 20% of people, warts disappear within 6 months, requiring no treatment.

Key points

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a DNA virus that infects the basal epithelium of the skin and oral and genital mucosa

- HPV is extremely prevalent and acquired by nearly all sexually active adults during their lifetime

- HPV is most commonly transmitted through sexual intercourse

- Important risk factors include early sexual intercourse, a high number of sexual partners, condomless sex, HIV infection and immunosuppression

- Most HPV infections are asymptomatic and cleared by the immune system within 2 years

- High-risk HPV include HPV 16 and HPV 18, which cause cancers such as cervical cancer

- Low-risk HPV includes HPV 6 and HPV 11, which can cause genital warts

- Genital warts are often asymptomatic but may cause pruritus, bleeding, pain and urinary symptoms

- Warts disappear within 6 months in 20% of cases, but treatment can be topical or ablative

- HPV can be prevented by vaccination, which is offered to girls and boys aged 11-14, MSM under age 45, transgender individuals, sex workers, and people living with HIV

Reviewer

Dr Hayley Wood

Consultant in Genitourinary Medicine

Royal Derby Hospital

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- de Sanjose, S., Brotons, M. and Pavon, M.A., 2018. The natural history of human papillomavirus infection. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology, 47, pp.2-13.

- Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Collado JJ, Gómez D, Muñoz J, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Summary Report 22 October 2021.

- Centre for Disease Control, 2022. HPV Available at [LINK]

- Public Health England, 2014. Human papillomavirus (HPV): the green book, chapter 18a.

- Public Health England, 2019. Sexually transmitted infections and screening for chlamydia in England. Health Protection Report, 13(19), pp.1-38.

- Sonnenberg, P., Tanton, C., Mesher, D., King, E., Beddows, S., Field, N., Mercer, C.H., Soldan, K. and Johnson, A.M., 2019. Epidemiology of genital warts in the British population: implications for HPV vaccination programmes. Sexually transmitted infections, 95(5), pp.386-390.

- Roden, R.B. and Stern, P.L., 2018. Opportunities and challenges for human papillomavirus vaccination in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 18(4), pp.240-254.

- Mammas, I.N., Sourvinos, G. and Spandidos, D.A., 2009. Human papilloma virus (HPV) infection in children and adolescents. European journal of pediatrics, 168(3), pp.267-273.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017. Warts – anogenital. Available at [LINK]

- Jmarchn. Penile warts in the foreskin. License: [CC BY-SA]

- CDC Public Health Image Library. 16733. License: [Public domain]

- CDC Public Health Image Library. 16734. License: [Public domain]

- Dave Bray, MD. Close-up view of typical molluscum bumps. License: [Public domain]

- AndyRich48. Pearly Penile Papules. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (online) London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, 2022. Human papillomavirus vaccine. Available at [LINK]

- NHS England. GOV.UK. 2022. HPV immunisation programme: changes from April 2022 letter. [online] Available at [LINK]