- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Sudden painless loss of vision is a red flag symptom requiring urgent referral to an eye care professional.

This article will cover the underlying causes of painless loss of vision.

It is important to distinguish sudden painLESS loss of vision from sudden painFUL loss of vision, gradual loss of vision and transient loss of vision, as these have different underlying pathology.

Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy

Ischaemia of the optic nerve can occur at different anatomical locations with a wide range of underlying aetiologies.

Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AION) refers to ischaemia of the optic nerve which results in visible optic disc swelling. If optic nerve ischaemia is present without visible optic disc swelling it is referred to as posterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (PION).

AION is broadly divided into arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AAION) and non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (NAION).

Arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy is often referred to as temporal/giant cell arteritis.

Aetiology

AAION is due to inflammation of the temporal arteries and subsequent thrombosis of the short posterior ciliary arteries which leads to ischaemia of the optic disc. The underlying disease process is almost exclusively temporal/giant cell arteritis.

NAION is due to non-inflammatory disease of small blood vessels (short posterior ciliary arteries) supplying the optic nerve, such as atherosclerosis. NAION is more common than temporal arteritis and has a better prognosis.

Risk factors

Risk factors for AAION are the same as the risk factors for temporal/giant cell arteritis and include:

- Age: > 50

- Female sex

- Past medical history of polymyalgia rheumatica

Risk factors for non-arteritic AION include:

- Age: >50, although typically younger than that of temporal/giant cell arteritis at presentation

- Cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and smoking

- Anaemia

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of temporal/giant cell arteritis include:

- Sudden loss of vision

- New-onset headache (particularly around the temporal region)

- Jaw claudication

- Scalp tenderness

- Diplopia

Typical symptoms of NAION include:

- Acute painless loss of vision in one eye (often described as blurring or cloudiness)

- Patients often become aware of vision loss upon waking in the morning

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Systemic features: fatigue, malaise, weight loss, anorexia, depression

- Past medical history of polymyalgia rheumatica

Clinical examination

Typical clinical findings of temporal/giant cell arteritis include:

- Profoundly reduced visual acuity

- Dyschromatopsia (reduced colour vision)

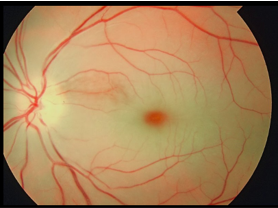

- Fundoscopy: pale swollen optic disc

- Pupil examination: relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD)

- Scalp and temporal artery tenderness

- Pulseless temporal artery

Typical clinical findings of NAION include:

- Reduced visual acuity (less profound compared to temporal/giant cell arteritis)

- Dyschromatopsia (reduced colour vision)

- Fundoscopy: pale swollen optic disc with splinter haemorrhages

- Pupil examination: RAPD

- Visual fields: altitudinal field defect (most commonly inferior hemisphere)

A pale swollen disc (Figure 1) in a patient over the age of 50 should be presumed to represent temporal/giant cell arteritis until proven otherwise.

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Visual acuity assessment: to determine the severity of sight loss

- Colour vision assessment: if reduced it indicates an optic neuropathy

- Blood pressure: hypertension is a risk factor NAION

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations for AAION include:

- Full blood count: normochromic anaemia and an increased platelet count may be noted

- C-reactive protein: typically raised in suspected cases of temporal/giant cell arteritis

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): an ESR greater than 50 is considered significant

- Liver function test (LFT): may display mild elevation of alkaline phosphates and transaminases

Relevant laboratory investigations for NAION include:

- Glucose and HbA1c: to identify undiagnosed diabetes mellitus

- Lipid profile: to identify hypercholesterolaemia which is a risk factor for NAION

- Vasculitis screen: if the patient is under the age of 50

Other investigations

Other relevant investigations include:

- Temporal artery biopsy: a positive biopsy will demonstrate mononuclear cell infiltration or granulomatous inflammation with multinucleate giant cells. The biopsy is considered the gold standard investigation but is becoming less favourable due to the presence of false negatives. False negatives are due to skip lesions. The biopsy needs to be performed within one week of steroid treatment otherwise the result may be inconclusive.

- Duplex ultrasound of temporal artery: will demonstrate a halo sign (due to oedema of the vessel) if positive for giant cell arteritis

Management

Temporal arteritis is treated with high-dose systemic steroids. These patients require an urgent referral to an ophthalmologist or rheumatologist. For more information, see the Geeky Medics article on temporal arteritis.

NAION has no proven treatment. Management should aim at optimising risk factors (e.g. hypertension) to prevent progression.

Complications

Untreated AAION will lead to blindness in the affected eye as well as an increased risk of second eye involvement within 7 days.

Key points

- Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy describes a condition where ischaemia causes visible damage to the optic disc.

- There are two types of anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy: arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy and non-arteritic optic neuropathy.

- Arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy is more commonly referred to as giant cell arteritis or temporal arteritis.

- A pale swollen disc in a patient over 50 is considered temporal/giant cell arteritis until proven otherwise.

- GCA is treated with high dose steroids and confirmed using a temporal artery biopsy.

- Non-arteritic ischaemic optic neuropathy is more common and has more favourable visual outcomes.

Table 1. Summary of differences between arteritic and non-arteritic AION.2

|

|

Arteritic AION | Non-arteritic AION |

|

Incidence per year |

1/100,000 |

10/100,000 |

|

Causes and associations |

Major

|

Major

Minor

|

|

Age |

70 years |

60 years |

|

Visual acuity and visual field defect |

Usually <6/60

|

Usually >6/60 Often have an altitudinal field loss |

|

Associated symptoms |

Scalp tenderness, jaw claudication, headache |

Usually none |

|

Optic disc |

Pale and swollen optic disc

|

Sectoral swollen optic disc Commonly hyperaemic |

|

ESR |

Raised |

Normal |

|

CRP |

Raised |

Normal |

|

Platelet count |

Raised |

Normal |

|

Risk to the other eye |

10% (if treated); 95% (if untreated) |

|

|

Prognosis |

15% improve |

40% improve |

Retinal artery occlusion

Retinal artery occlusion is an ocular emergency requiring urgent assessment and management. The retina infarcts after approximately 90 minutes of oxygen deprivation.

Types of retinal artery occlusion:

- Central retinal artery occlusion

- Branch retinal artery occlusion

Aetiology

Retinal artery occlusion occurs secondary to emboli obstructing the retinal artery or thrombus formation within the artery itself.

Risk factors

Risk factors for retinal artery occlusion include:

- Atherosclerotic: hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking

- Haematological: antiphospholipid syndrome, malignancy (e.g. myeloma, leukaemia or lymphoma), sickle-cell anaemia

- Inflammatory: temporal arteritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Infective: toxoplasmosis, syphilis, Lyme disease

- Pharmacological: combined oral contraceptive pill, recreational drug use (e.g. cocaine)

Clinical features

History

Patients present with sudden unilateral painless visual loss.

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Past medical history: amaurosis fugax, atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease, thrombophilia, malignancy

- Family history: thrombophilia

- Drug history: combined oral contraceptive pill and cocaine

- Review of systems: symptoms of temporal arteritis (especially in patients aged over 50) and cerebrovascular disease

Clinical examination

Visual assessment findings:

- Reduced visual acuity

- Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD)

Fundoscopy findings:

- Narrowing of the retinal arteries/veins

- Retinal pallor (due to ischaemia)

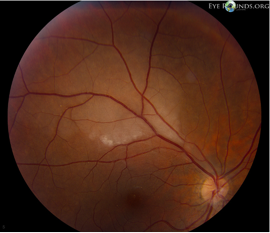

- Cherry-red spot (Figure 2)

- Neovascularisation of the optic disc, fundus or iris (chronic ischaemia)

- Raised intra-ocular pressure

The area of ischaemia (retinal pallor) noted on fundus examination is typically sectoral in the context of a branch retinal artery occlusion (Figure 3).

Other relevant clinical findings on examination include:

- Arrhythmias: can lead to thrombus formation within the heart and dislodge to other areas of the body such as the blood vessels supplying the retina. The most common arrhythmia associated with retinal artery occlusion is atrial fibrillation.

- Heart murmurs: indicative of valvular heart disease or infective endocarditis

- Carotid bruits: suggests the presence of carotid artery stenosis

- Temporal artery tenderness: associated with central retinal artery occlusion

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Visual acuity

- Colour vision

- Pupil assessment: RAPD

- Blood pressure: hypertension

- ECG: atrial fibrillation

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- FBC

- ESR and CRP: to exclude temporal/giant cell arteritis

- Coagulation screen

- Glucose

- Lipid profile

Relevant laboratory investigations for patients below the age of 50 (where atherosclerosis is less likely) include:

- Vasculitis screen: antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-nuclear cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), rheumatoid factor, anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM), immunoglobulins4

- Serum protein electrophoresis

- Infection screen (serology): treponemal, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, borrelia

- Thrombophilia screen

- Treponemal serology

- Thyroid function test

Imaging investigations

Relevant imaging investigations include:

- Carotid artery doppler: to evaluate the presence of carotid stenosis

- Chest X-ray: to detect sarcoidosis and tuberculosis (in patients below the age of 50)

- Echocardiography: it is particularly pertinent if there is a past medical history of rheumatic fever, valvular heart disease or IVDU

Management

There are two primary objectives in the initial management of retinal artery occlusion.

The first objective is to rule out temporal/giant cell arteritis.

The second objective applies if the patient has presented within 90 minutes, here an effort is made to dislodge the embolus. Options include ocular massage, re-breathing into a bag (increases carbon dioxide levels promoting vasodilation), and reducing intraocular pressure with intravenous acetazolamide or through an anterior chamber paracentesis.5

A retinal artery occlusion should be managed as a stroke and therefore prompt referral to the stroke team is required. Patients should be started on 300mg aspirin for 14 days as well as secondary prevention.

The patient should also be informed not to drive for one month and may resume driving as long as there is satisfactory clinical recovery. In the United Kingdom, patients who drive commercial vehicles (e.g. bus/lorry) must notify the DVLA and not drive for one year.6

Complications

Complications of retinal artery occlusion include:

- Neovascularisation of the optic disc and fundus: new brittle vessels are formed around the optic disc and fundus

- Neovascularisation of the iris: the new blood vessels grow on the iris and can occlude the drainage angle thus preventing the drainage of aqueous humour, this results in a raised intraocular pressure

Key points

- There are two main types of central retinal artery occlusion and branch retinal artery occlusion

- Classical findings of a central artery occlusion include the cherry-red spot located in the fovea

- Retinal artery occlusion an ophthalmic emergency. If the patient presents within 90 minutes immediate action is required to help dislodge the embolus.

- A retinal artery occlusion should be managed as a stroke and therefore prompt referral to the stroke team is required.

- The patient needs to be informed that they are not allowed to drive for at least one month.

Retinal vein occlusion

Retinal vein occlusion is one of the most common causes of sudden unilateral painless loss of vision. Loss of vision occurs due to cystoid macular oedema (fluid in the macula).

Retinal vein occlusions are either central retinal vein occlusions or branch retinal vein occlusions. They can also be ischaemic or non-ischaemic. Ischaemic retinal vein occlusions have a worse prognosis.

Aetiology

Retinal arterioles and arteries share an adventitial sheath with retinal venules and veins. This means that the atherosclerotic process in the retinal arteries and arterioles cause subsequent changes in the veins such as endothelial cell loss, turbulent flow, and thrombus formation.

Risk factors

Risk factors for retinal vein occlusion include:

- Age: over 50% of cases occur in patients over the age of 65

- Cardiovascular disease: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia

- Hypercoagulable state: thrombophilia, malignancy (myeloma, leukaemia), or antiphospholipid syndrome

- Auto-immune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Behcet’s disease or sarcoidosis

- Ophthalmic disease: glaucoma

- Drugs: combined oral contraceptive pill

Clinical features

History

Patients present with sudden unilateral painless visual loss.

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Past medical history: atherosclerotic risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, auto-immune conditions), previous DVT or recurrent miscarriage, active/previous malignancy

- Past ocular history: glaucoma

- Family history: can highlight the presence of thrombophilia

- Social history: smoking

- Medication: combined oral contraceptive pill

Clinical examination

Typical clinical findings of retinal vein occlusion include:

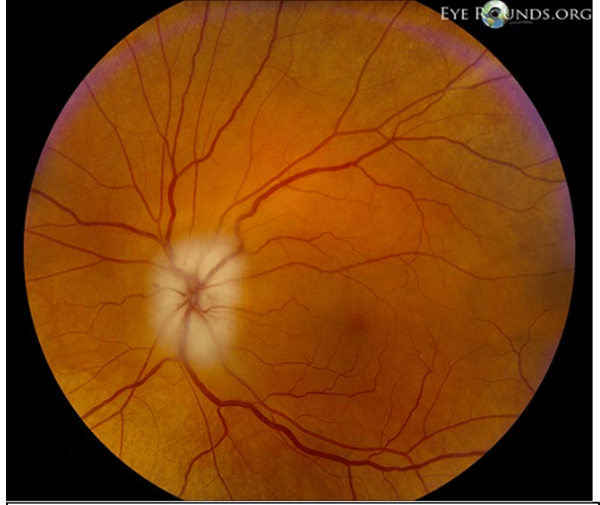

- Retinal haemorrhage: central retinal vein occlusion has a haemorrhage in all 4 quadrants for central (Figure 4). In branch retinal vein occlusion it is more localised (Figure 5).

- Dilated tortuous veins

- Relative afferent pupillary defect: suggests ischaemic vein occlusion

- Cystoid macular oedema: may sometimes be seen at presentation if the patient has presented late

Typical clinical findings suggestive of ischaemic retinal vein occlusion include:

- RAPD

- Cotton wool spots: these lesions appear as white fluffy clouds and represent retinal ischaemia

- Neovascularisation of the optic disc, fundus and/or iris is a complication of long-standing ischaemia

- Raised intraocular pressure: neovascular glaucoma

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Visual acuity: to determine the severity of vision loss

- Colour vision: to identify an optic neuropathy

- Pupil examination: particularly checking for a relative afferent pupillary defect

- Intraocular pressure: glaucoma is a risk factor

- Blood pressure: hypertension is a risk factor

- ECG

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations for all patients include:

- Full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein

- Random blood glucose

- Lipid profile

- Coagulation screen

- Plasma electrophoresis

Relevant laboratory investigations for patients below the age of 50 (where atherosclerosis is less likely) include:

- Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme

- Anticardiolipin, lupus anticoagulant

- Autoantibodies: rheumatoid factor, ANA, ANCA

- Thrombophilia screen: protein C and S, and factor V Leiden

- Treponemal serology

Imaging

Imaging is not routinely required unless the patient has an atypical presentation or is below the age of 50. In these circumstances, a chest X-ray is indicated to look for sarcoidosis.

Management

Management involves identifying and treating underlying medical conditions. Macular oedema and neovascularisation of the fundus or iris should be excluded. If found to be present, neovascularisation is often treated with laser therapy and macular oedema with anti-VEGF injections.

Complications

Complications of retinal vein occlusion include:

- Cystoid macular oedema: this describes a fluid build-up in the macular region

- Neovascular glaucoma whereby the angle of the eye is occluded by new blood vessels

Key points

- There are two main types of central retinal vein occlusion and branch retinal vein occlusion

- Retinal vein occlusions can also be divided into ischaemic and non-ischaemic, where the former carries a worse prognosis

- The most common cause for loss of vision is due to cystoid macular oedema

- Management involves identifying and treating underlying medical conditions

- Complications include macular oedema (treated with anti-VEGF injections) and neovascular glaucoma (treated with laser therapy).

Retinal detachment

Retinal detachment occurs when the retina pulls away from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

This results in the accumulation of fluid in the potential space between the two layers, and if left untreated the fluid accumulation can cause progression of the retinal detachment resulting in blindness.

Retinal detachment is sight-threatening. However early detection and treatment can significantly improve the prognosis.

Aetiology

There are three main types of retinal detachments. They are classified based on how the retina pulls away from its underlying structures.

- Rhegmatogenous (Greek, rhegma means break): a retinal tear permits fluid from the vitreous to enter the new potential space. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachments are the most common.

- Non-rhegmatogenous (tractional): when scar tissue grows over the retina tractional forces pull the retina away which can lead to a retinal detachment. It is commonly associated with diabetic retinopathy.

- Non-rhegmatogenous (exudative): occurs when fluid accumulates beneath the retina (subretinal fluid), usually due to inflammation such as uveitis. Progressive accumulation of subretinal fluid can cause the retina to detach.

Aetiology

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is preceded by a posterior vitreous detachment caused by liquification of the vitreous gel. A posterior vitreous detachment can lead to a retinal tear.

Once a retinal tear has occurred a new potential space allows for the liquefied vitreous to enter the new potential space causing a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Therefore, the aetiology follows that of posterior vitreous detachment and retinal tears.

The causes of tractional retinal detachment include:

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (most common)

- Retinal vein occlusion

- Proliferative sickle cell retinopathy

- Retinopathy of prematurity

- Blunt trauma

The causes of exudative retinal detachment include:

- Choroidal tumours such as melanoma and metastases

- Inflammation involving the posterior segment such as posterior uveitis

- Choroidal neovascularisation

- Hypertensive choroidopathy

- Iatrogenic such as vitrectomy or laser treatment

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of a retinal detachment include:

- Sudden painless loss of vision often described as a dark curtain or shadow

- New onset of floaters (black dots)

- New onset of flashes often in the periphery

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Trauma

- Past medical history: diabetes and myopia (short-sightedness)

- Past surgical history: previous ophthalmic operations (e.g. cataract operation) increases the risk for retinal detachment

Clinical examination

Typical clinical findings of a retinal detachment include:

- Visual acuity: functions as a crude guide to determine if there is any macular involvement. The visual acuity is normal if the macula is still attached (macula on) and severely impaired if the macula is detached (macula off). It is important to perform crude confrontational visual fields assessment as this could pick up a peripheral retinal detachment.

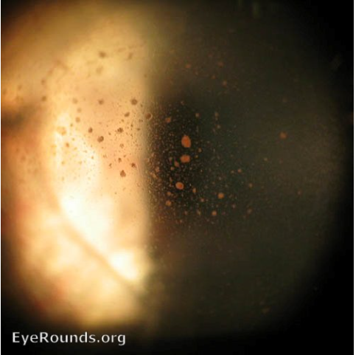

- An opaque translucent layer (Figure 6)

- Posterior vitreous detachment

- Vitreous haemorrhage

- Retinal tears: these appear as tears in a detached retina (Figure 7)

- Tobacco dust (Figure 9)

Investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Visual acuity

- Intraocular pressure

- Fundoscopy

Specialist investigations

Clinical examination is often sufficient to diagnose a retinal detachment. However, if the fundal view is very hazy a B-scan (ultrasound of the eye) is performed to visualise the fundus and rule out any retinal tears or detachments (Figure 8).

Since posterior vitreous detachment, vitreous haemorrhage and retinal tears are all associated with rhegmatogenous retinal detachments the initial approach to these patients is similar.

Management

In patients with suspected retinal detachment, an urgent referral to ophthalmology for assessment and urgent retinal detachment surgery is required.

Surgical management of retinal detachment may include:

- Pars plana vitrectomy: a ‘key-hole’ procedure where the entry points are through the pars plana. A vitrectomy is performed (removal of vitreous humour). Often it is substituted with a gas or silicone oil endotamponade to provide pneumatic pressure to keep the detached retina in place.

- Scleral buckle: silicone bands are permanently placed around the exterior aspect of the globe, beneath the extraocular rectus muscles. They act to relieve any traction and support retinal tears. Scleral buckling is often combined with retinopexy and cryopexy.

Tractional detachments usually require relief of the tractional elements through peeling off the epiretinal or sub-retinal membranes that give rise to the tractional forces.

Exudative retinal detachments tend to be managed non-surgically as treatment is targeted towards the underlying disease.

Key points

- A retinal detachment refers to when the neurosensory retina has detached from the underlying RPE layer

- There are three types of retinal detachments, rhegmatogenous, tractional, and exudative all with different underlying pathologies

- Posterior vitreous detachment, vitreous haemorrhage and retinal tears are all associated with rhegmatogenous retinal detachments as they play a part in its pathogenesis

- Rhegmatogenous retinal detachments are either macula on where the macula is still attached or macula off where the macula is detached

- In patients with suspected retinal detachment, an urgent referral to ophthalmology for assessment and urgent retinal detachment surgery is required

Vitreous haemorrhage

Vitreous haemorrhage is a bleed into the gel-like filling (vitreous humour) in the globe of the eye. This occurs when damage to the retinal blood vessels has occurred.

Often the blood vessels affected are those formed due to neovascularisation. These vessels are new brittle vessels prone to leaking or breaking in the event of a retinal tear or retinal detachment. As such, vitreous haemorrhage is often suggestive of other underlying pathology.

Aetiology

The majority of cases of vitreous haemorrhage are due to proliferative diabetic retinopathy, posterior vitreous detachment, retinal breaks, retinal detachment or trauma.

Other less common causes include:

- Ischaemic retinal vein occlusion: the retinal ischaemia drives neovascularisation

- Proliferative sickle cell retinopathy

- Neovascular age-related macular degeneration

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage (Terson’s syndrome)

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of vitreous haemorrhage include:

- Blurred vision: the vitreous is a transparent gel and if the vitreous humour is clouded or filled with blood the vision will be impaired

- Floaters: these patients will often describe it as a “gush” of floaters and what they are in fact seeing is the vitreous haemorrhage

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- History of trauma

- Past medical history: diabetes, wet age-related macular degeneration or sickle cell retinopathy as these conditions cause neovascularisation

Clinical examination

Clinical findings of vitreous haemorrhage depend on the severity and duration of the haemorrhage:

- Severe vitreous haemorrhage: hazy fundal view and absent red reflex

- Mild vitreous haemorrhage: partially obscured fundal view due to a localised vitreous haemorrhage

- Chronic vitreous haemorrhage: appears as a yellow lesion. It gains this appearance due to the haemoglobin breakdown

Vitreous haemorrhage suggests the presence of underlying pathology. It is important to look for retinal tears and retinal detachments.

Clinical signs of a retinal tear may be the presence of tobacco dust in the vitreous (Figure 9). This is released by retinal pigment epithelial cells in the anterior vitreous and is best visualised on the slit lamp.

Management

The main goals of treatment are to preserve vision, stop the bleeding, and repair any damage to the retina to prevent permanent loss of vision

Management options for vitreous haemorrhage include:

- Observation: a vitreous haemorrhage without a retinal tear or detachment often resolves within a couple of weeks. During this time, it is important patients are followed-up to detect any retinal tears or detachment. These patients should also be given warning signs for retinal detachment (e.g. flashing lights, new floaters and change in vision). The patient should be advised to avoid any heavy lifting as an increase in blood pressure may disrupt a clot and cause new active haemorrhage.

- Laser therapy: performed for patients with proliferative vasculopathies (e.g. proliferative diabetic retinopathy) and retinal tears

- Surgical intervention: indicated in patients with posterior vitreous detachment and a non-clearing vitreous haemorrhage lasting several months or a retinal detachment.

Key points

- Vitreous haemorrhage is a bleed into the vitreous humour in the globe of the eye.

- It is a marker for underlying pathology, it is important to look for neovascularisation, retinal tears and retinal detachment.

- Most cases of vitreous haemorrhage are due to proliferative diabetic retinopathy, posterior vitreous detachment, retinal breaks, retinal detachment or trauma.

- Observation is indicated when there is a vitreous haemorrhage without a retinal tear or detachment. Laser therapy is indicated if neovascularisation or a retinal tear is present.

- Surgical intervention is required in non-clearing vitreous haemorrhage.

Reviewer

Dr Taiwo Makanjuola

Ophthalmology registrar

Aberdeen Royal Infirmary

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Jesse Vislisel MD. Giant cell arteritis. License: [CC-BY-NC-ND]. Available from: [LINK]

- Alastair K. O. Denniston and Philip I. Murray. Oxford Handbook of Ophthalmology (4th edition). Published in 2018

- sidthedoc. Central retinal artery occlusion. License: [CC-BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Chen, J. Branch retinal artery occlusion. License: [CC-BY-NC-ND]. Available from: [LINK]

- Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency. Neurological disorders: assessing fitness to drive. Last updated 4th March 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Nika Bagheri and Brynn N. Wajda. The Wills Eye Manual (7th Edition). Published in 2017

- Andrew Doan MD, Central Retinal Vein Occlusion. License: [CC-BY-NC-ND]. Available from: [LINK]

- Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (UKMMC). Branch retinal vein occlusion. Licence: [CC-BY].

- Cindy Montague. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. License: [CC-BY-NC-ND]. Available from: [LINK]

- Cindy Montague. Retinal tear. License: [CC-BY-NC-ND]. Available from: [LINK]

- Strohbehn A. Sohn EH. B-scan Retinal Detachment. License: [CC-BY-NC-ND]. Available from: [LINK]

- Andrew Doan MD, Tobacco dust. License: [CC-BY-NC-ND]. Available from: [LINK]