- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

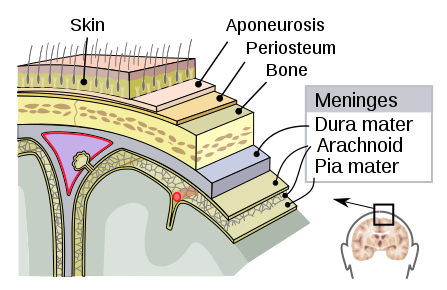

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) describes bleeding into the subarachnoid space of the brain, which is located between the arachnoid and pia mater meningeal layers.

SAH is a devastating and life-threatening condition, which damages the brain through hypoxia, increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and direct cranial injury.

If left untreated, it can lead to permanent neurological disabilities, coma and death. Death rates from the initial SAH are reported to range between 40-60%.1

Aetiology

Anatomy

These meningeal layers cover the brain and have a protective effect against intracerebral infections (Figure 1).

Arachnoid villi are present in the arachnoid mater, which continuously absorb cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulating around the central nervous system (CNS).

Causes of subarachnoid haemorrhage

SAH can be associated with a traumatic injury or be spontaneous.

The majority of SAHs are caused by traumatic injuries, such as road traffic collisions, however, this article will focus on spontaneous SAH.

Common causes of spontaneous SAH include:

- Intracranial aneurysms: 70%

- Arteriovenous malformation (AVM): 10 %

- SAH of unknown aetiology: 15%

- Rare disorders: <5%

Risk factors

Risk factors for spontaneous SAH include:4

- Hypertension

- Smoking

- Family history

- Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD)

- Age over 50 years

- Female sex (approximately 1.5x baseline risk)

Clinical features

Most intracranial aneurysms remain asymptomatic until they rupture and cause a haemorrhage.

History

Typical symptoms of SAH include:

- Sudden onset severe headache, reaching maximum intensity within seconds (often referred to as a “thunderclap headache”)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Photophobia

The sudden onset of headache is a key feature of SAH. It is important to establish the time to maximal intensity, which is generally within a few minutes in SAH.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to headache history taking.

Clinical examination

Typical clinical findings in SAH include:

- Reduced level of consciousness: loss of consciousness can occur secondary to raised intracranial pressure

- Neck stiffness: occurs secondary to meningeal irritation

- Kernig’s sign: the inability to extend the knee due to pain when the patient is supine and the hip and knee are flexed to 90o

A positive Kernig’s sign is caused by irritation of motor nerve roots passing through inflamed meninges as they are under tension.

Kernig’s sign is, however, unreliable and is only a test of non-specific meningeal irritation, meaning that other pathology such as bacterial or viral meningitis can also cause a positive result.

Investigations

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- FBC: to obtain a baseline

- U&Es: to obtain a baseline

- Coagulation studies: useful to know prior to lumbar puncture or surgery

Imaging

Relevant imaging investigations include:

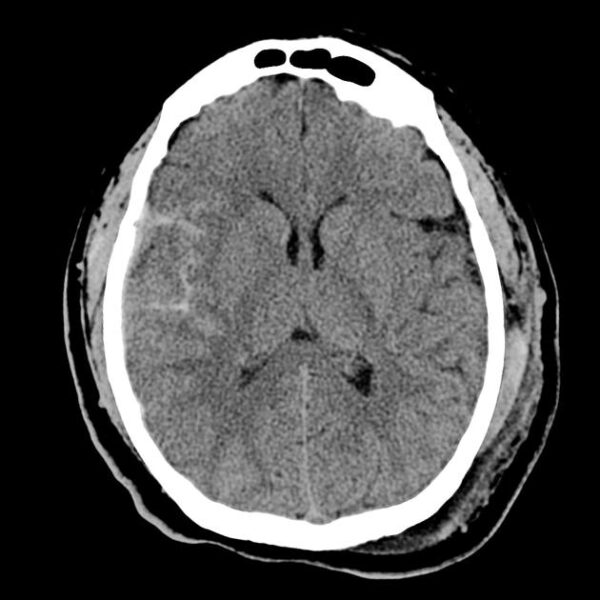

- Plain CT head scan: this is to look for evidence of blood in the subarachnoid space or hydrocephalus

- CT angiogram: this highlights the arterial vessels of the brain using contrast, which can sometimes allow identification of an aneurysm

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to CT head interpretation.

Lumbar puncture

A lumbar puncture is only necessary if SAH is suspected but the CT scan does not show any evidence of bleeding or raised intracranial pressure.

A lumbar puncture needs to be performed at least 12 hours after the onset of symptoms, for the result to be reliable.

Visual inspection and chemical analysis of the CSF is done to identify xanthochromia. This is when the CSF has become stained yellow due to the infiltration of blood from the haemorrhage.

Analysis can reveal an increase in pigments, such as bilirubin and oxyhaemoglobin, resulting from haemolysis of red blood cells.

See our guide to CSF analysis to learn more.

Management

Both traumatic and spontaneous SAH are medical emergencies, requiring prompt treatment.

ABCDE assessment

Initially, a thorough ABCDE assessment should be performed, with urgent problems identified and managed appropriately to stabilise the patient.

Airway

The airway should be assessed to ensure it is patent. Patients with a reduced level of consciousness, as can be the case in SAH, are at risk of occluding their airway and may require intervention (e.g. oropharyngeal airway or intubation).

Breathing

Record respiratory rate and SpO2. Patients may be hypoxic secondary to an occluded airway or early aspiration pneumonia.

Circulation

Blood pressure and pulse should be recorded. Intravenous fluids may need to be administered to maintain adequate blood pressure.

Patients may require electrolyte replacement (hyponatraemia is common in SAH).

Calcium channel blockers (e.g. nimodipine) must be given to reduce cerebral artery spasm and secondary cerebral ischaemia.

Disability

The patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) should be assessed and if below 8, anaesthetic input may be required to manage the airway.

Invasive intracranial pressure monitoring may be required if the patient’s GCS deteriorates.

Exposure

A thorough assessment of the patient’s entire body should be performed to recognise secondary injuries (either due to primary trauma or secondary collapse).

Neurosurgical referral

All SAH cases should be discussed urgently with a local neurosurgical team. In selected cases, surgery is undertaken to manage the cause of the bleed or to manage intracranial pressure (e.g. ventricular drain).

Surgical intervention may involve:

- Obliteration of the ruptured aneurysm: this can be done via clipping, insertion of a fine wire coil or other endovascular treatments.

- Balloon angioplasty if the patient develops cerebral vasospasm.

- Ventricular drainage for cases with secondary hydrocephalus.

Complications

Obstructive hydrocephalus

Obstructive hydrocephalus occurs due to blood pooling in the ventricular system, resulting in obstruction of CSF drainage. This causes a progressive rise in the intracranial pressure, ultimately leading to a deteriorating GCS and death if untreated.

Obstructive hydrocephalus can be diagnosed on a CT scan, as the ventricles appear enlarged (ventriculomegaly).

A ventricular drain is often inserted to maintain a viable intracranial pressure.

Arterial vasospasm

This is a serious complication of SAH and a poor prognostic feature. Cerebral arteries vasoconstrict, reducing blood supply to the cerebral tissue distal to the area of vasospasm, leading to secondary brain ischaemia.

Calcium-channel blockers such as nimodipine have been shown to reduce the degree of vasospasm.

Re-bleeding of aneurysms

Re-bleeding of aneurysms is a leading cause of mortality in the context of SAH.

Neurological deficits

Long-term neurological deficits can occur secondary to direct (e.g. haemorrhage) or indirect (raised ICP and vasospasm) damage to cerebral tissue.

Prognosis

The prognosis for SAH varies depending on the cause and severity of the bleed.

However, it is important to note that approximately 50% of patients die immediately, or soon after the haemorrhage.

Key points

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) describes bleeding into the subarachnoid space of the brain and is a medical emergency.

- SAH can be associated with a traumatic injury or be spontaneous.

- Risk factors for spontaneous SAH include hypertension, smoking, ADPKD and family history of SAH.

- Typical symptoms of SAH include a sudden, severe (‘thunderclap’) headache, photophobia, and neck stiffness.

- Clinical findings include decreased level of consciousness and meningism.

- The first-line investigation is a CT head, if this is normal, a lumbar puncture should be performed to look for xanthochromia.

- An ABCDE approach to initial management with early referral to neurosurgery is essential.

- Calcium channel blockers (e.g. nimodipine) must be given to reduce cerebral artery spasm and secondary cerebral ischaemia.

- Approximately 50% of patients die immediately, or soon after SAH.

Reviewer

Mr Konstantinos Lilimpakis

Neurosurgical Clinical Fellow

Editor

Samantha Strickland

Hull York Medical Student

References

- Kopitnik, T.; Samson, D. Management of subarachnoid emergency. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1993. 56: 947-959. Available from: [LINK]

- Kumar and Clarke: Anne Ballinger, Anne Ballinger, Parveen J. Kumar, Michael L. Clark Pages: 899 Size: 19.4 MB Format: PDF Publisher: Saunders Published: 29 September, 2011 p700-800

- Mysid, original by SEER Development Team. Image of meningeal layers. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Brain Aneurysm Foundation. Risk factors. Published online in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- James Heilman, MD. CT scan of spontaneous SAH. License: [CC-BY-SA] Available from: [LINK]

- Radiopaedia (Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard). case rID: 4852. Available from: [LINK]

- Sonpal, N. & Fischer, C. 2015. General surgery: correlations and clinical scenarios [eBook]. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- The Internet Stroke Centre. Subarachnoid Haemorrhage. Available from: [LINK]

- BMJ Best Practice. Subarachnoid Haemorrhage. Available from: [LINK]