- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

The meninges (from ‘meninx’ meaning membrane) are a set of distinct membranes that cover and encase the brain and spinal cord.

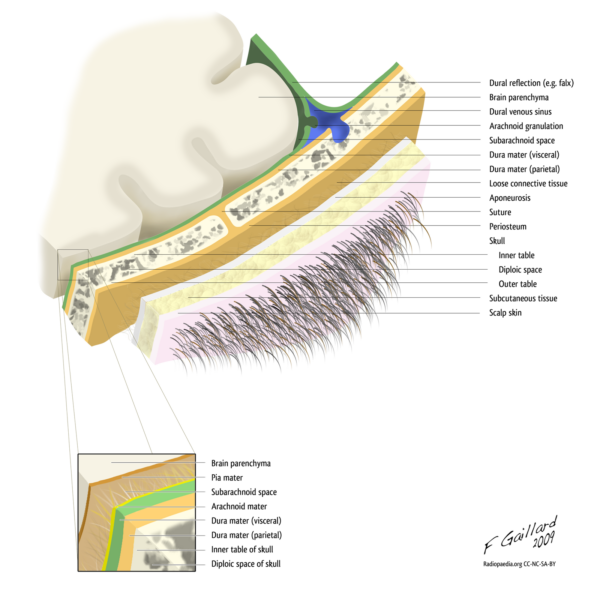

There are three layers from superficial to deep:

- Dura mater: the outermost layer that is directly underneath the skull. It is tough, fibrous and inextensible. It consists of two layers, periosteal and meningeal.

- Arachnoid mater: the middle layer that lies directly beneath the dura mater. It is translucent and pliable.

- Pia mater: the innermost layer of the meninges. It is relatively very thin and fragile. This layer is adherent to the surface of the brain and spinal cord following the gyri and sulci of the brain’s surface. The gyri are the ‘ridges’ and the sulci are the ‘furrows’, which together form the undulating folds of the brain’s surface.

Etymology

The term ‘dura mater’ stems from the Latin for ‘hard mother’, in turn being derived from the Arabic for ‘coarse mother’. ‘Hard’ and ‘coarse’ are merely reflections of the dura’s composition.

‘Arachnoid’ refers to the spider-web-like appearance of the arachnoid mater.

‘Pia’ or ‘little’ describes how small and fragile this layer is.

Although there are a number of views as to why ‘mater’ is used, it is most often suggested that ‘mother’ refers to the protective nature of the meninges – ‘the mothers of the brain’.

Layers of the scalp

The mnemonic SCALP can be used to recall the layers of the scalp:

- Skin

- Connective tissue (dense)

- Aponeurotic layer

- Loose connective tissue

- Pericranium

Function of the meninges

The meninges have two primary functions:

- To provide a supportive framework for the blood vessels of the brain and the cranial cavity.

- To form a series of distinct compartments, that in combination with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), protect the brain from mechanical injury.

Dura mater

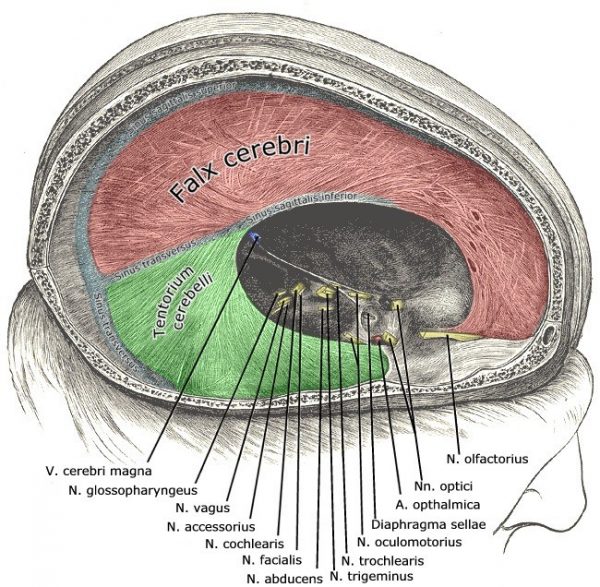

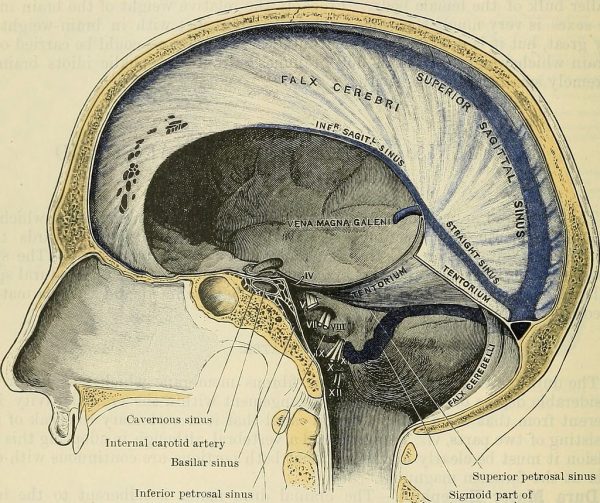

The dura mater compartmentalises the brain (via falx cerebri and tentorium cerebelli) thus preventing directional movement of the brain within the cranial vault that would normally cause injury. It also contains the cerebral venous drainage sinuses.

Arachnoid mater

The arachnoid mater maintains a barrier between the pia and dura mater, creating the subarachnoid space containing the cerebral arteries (that supplies oxygenated blood to the brain parenchyma) and CSF (that provides a cushion for the brain).

Pia mater

The pia mater has perforations which allow the subarachnoid arterial supply to reach the brain parenchyma.

Macroscopic anatomy

Compartments of the dura mater

The dura mater is comprised of two distinct layers, the periosteal (superficial) and meningeal (deep) layers. Both layers follow the contours of the internal surface of the skull.

The meningeal layer invests in and reflects inwards at the cranial sutures creating partitioning ‘walls’ that compartmentalise the brain. The subsequent compartments are:

- Falx cerebri: divides the cerebral hemispheres

- Tentorium cerebelli: divides the cerebrum from the cerebellum creating the supratentorial and infratentorial compartments

- Falx cerebelli: divides the cerebellar hemispheres

- Diaphragm sellae: covers the pituitary gland and the sella turcica

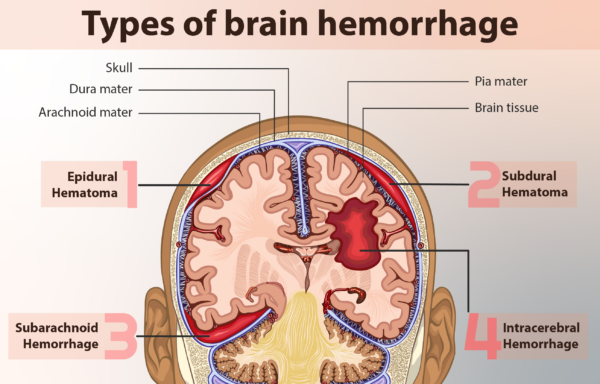

Clinical relevance: Extradural haematoma

An extradural haematoma is typically caused by an intracranial arterial bleed. Blood accumulates outside the dura, between the periosteal dura and the inner skull surface. The blood is confined by dural investments in cranial sutures.

Extradural haematoma appears as a ‘lentiform’ or lens-shaped opacity on a CT scan (resembling half a lemon).

The typical presentation of a patient with an extradural haematoma includes:

- Trauma to the pterion (the junction of the frontal, temporal, parietal and sphenoid bones, which is the weakest area of the skull, making it vulnerable to fracture). This, in turn, causes a rupture of the middle meningeal artery (which traverses the pterion).

- A fluctuant Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) and headache.

- In some cases, a classic ‘lucid interval‘ may be the presentation. This is where, following the initial neurological insult, there is a short period of complete resolution before symptoms resume and the patient deteriorates.

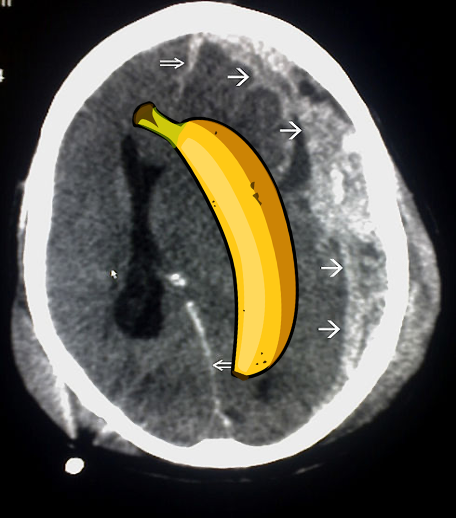

Clinical relevance: Subdural haematoma

A subdural haematoma is typically caused by an intracranial venous bleed, due to rupture of the dural bridging veins.

The haemorrhage occurs beneath the dura and above the arachnoid mater. The haemorrhage is not contained by dural investments and therefore can flow freely over the arachnoid surface.

A subdural haematoma appears as a crescent-shaped opacity on a CT head scan (somewhat resembling a banana).

The typical presentation of a patient with an extradural haematoma includes:

- There may be a history of head trauma, often it is minor, sometimes there is no trauma reported.

- It is a more likely pathology in elderly or chronic alcohol-dependent patients as both of these groups of patients have a degree of brain atrophy increasing risk of rupture to the bridging veins.

- Patients may present with a symptom profile ranging from a mild headache to weakness to seizures and severe neurologic deficit. In some cases, they may present with isolated parkinsonism or 3rd cranial nerve palsy.

Dura mater

Arterial supply

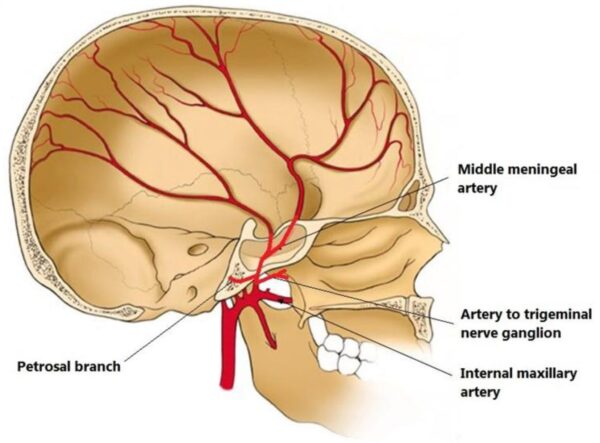

The dura mater receives its own blood supply, primarily from the middle meningeal artery (MMA).

This artery may be ruptured in blunt trauma to the head, specifically over the pterion, which is the weakest point in the skull and a point at which this artery overlies. The pterion is the meeting point of four cranial bones: the frontal, temporal, parietal and sphenoid bones. This injury results in an extradural (epidural) haematoma as described above.

Additionally, the less well described anterior and posterior meningeal arteries that supply the dura within the anterior and posterior cranial fossae, respectively, which are smaller territories than the MMA.

Venous drainage

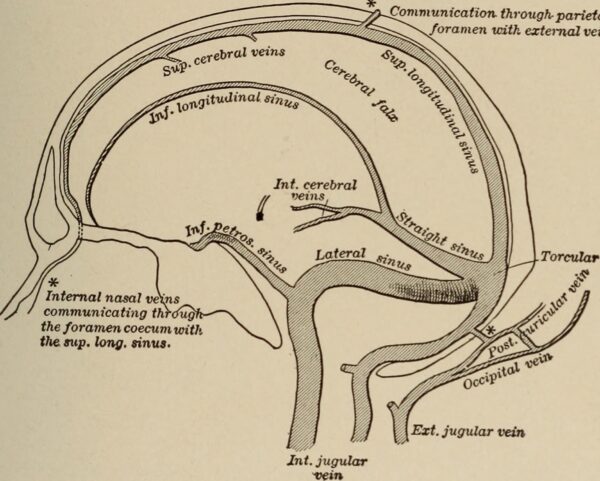

Between the two dural layers are the dural venous sinuses which drain deoxygenated blood from the brain back to the heart via the internal jugular veins (see Figure 8 below or read our guide here).

Innervation

The innervation of the dura mater is fairly complex. The dura mater can be divided into two regions, one above and the other below the tentorium cerebelli, forming the supratentorial and the infratentorial regions respectively.

The supratentorial dura mater is supplied by the small meningeal branches of the trigeminal nerve (CN V1, V2 and V3). This can be broken down further into:

- CN V1: supplies most of the supratentorial dura (falx cerebri, tentorium cerebelli, anterior fossa etc)

- CN V2 and V3: supplies the remaining dura in the middle cranial fossa

In contrast, the innervation for the infratentorial dura mater within the posterior cranial fossa is via the upper spinal cord cervical ganglion (includes C1, C2, and C3) as well as the meningeal branch of the vagus nerve (CN X).

Arachnoid mater

The arachnoid mater is a transparent, bi-layered structure found directly below the meningeal layer of the dura mater. It consists of loose connective tissue, it is avascular and has no innervation.

The subarachnoid space is filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) produced by the choroid plexus that circulates around the brain to:

- create an environment of buoyancy for the brain, thus reducing its perceived mass (from 1400g to 50g)

- create a cushioning layer, reducing the impact of jolting head movements on the brain

- maintain homeostasis of various neuroendocrine factors

- clear metabolic waste products that accumulate during the day

- reduce the impact of ischaemic conditions, as reductions in volume improve arterial supply to the brain

Clinical relevance: Subarachnoid haemorrhage

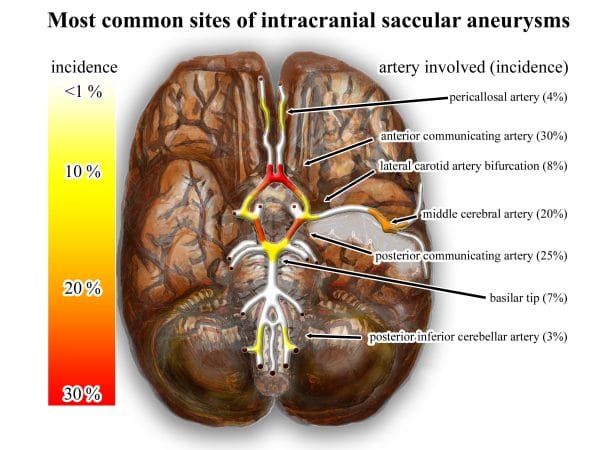

The blood vessels that supply the brain parenchyma itself are found within the subarachnoid space. A rupture of these vessels will result in subarachnoid haemorrhage.

The typical clinical presentation of a subarachnoid haemorrhage involves:

- Severe acute ‘thunderclap’ headache at the back of the head reaching maximal intensity within seconds to minutes.

- Often described as the worst headache the patient has ever experienced, or like being hit with a bat.

- Vomiting, confusion, neck stiffness, reduced GCS and focal neurological signs may be present.

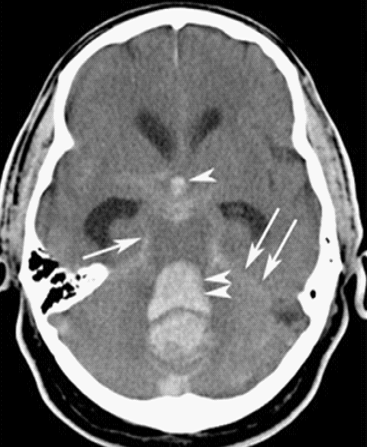

On CT imaging it presents as an enhancement (an area of hyperdensity or a brighter area – see arrows in Figure 9) tracking around the gyri or sulci, typically around the circle of Willis where ruptures of berry aneurysms can occur.

Pia mater

The pia mater is a transparent, single-layered structure found directly superficial to the cortical surface of the brain. It is delicate and firmly adherent to the brain’s surface, and it follows the flow of the sulci and gyri

The pia mater is impermeable to water but does allow for blood vessels to pierce through to supply the brain and spinal cord parenchyma

Clinical relevance: Meningitis

Meningitis is a life-threatening condition in which the pia and arachnoid mater become acutely inflamed. This can be either septic due to a bacterial infection, commonly Neisseria meningitidis, or it can be ‘aseptic’ where the cause can be due to a viral infection, an adverse drug reaction or other systemic diseases.

The typical clinical presentation of a patient with meningitis includes:

- Headache and fever

- Neck stiffness

- Photophobia

- Non-blanching, purpuric rash (if it has progressed to meningococcal septicaemia)

Spinal cord

At the level of the spinal cord, it is important to note that you will also encounter the same three meningeal layers along the full length.

The conus medullaris is the end of the spinal cord proper, which is located at the spinal level L1/2. From the conus medullaris, the pia mater extends caudally, surrounded by a dural sheath. This is the filum terminalis, whose function is to stabilise the spinal cord in the longitudinal plane by attaching to the posterior aspect of the first coccygeal segment.

The filum terminalis can be found nestled amongst the cauda equina, which are the individual nerve root fibres that extend inferiorly from the conus medullaris to meet their respective spinal foramina extending out to innervate the lower body.

Working laterally from the spinal cord, the meninges extend outwards covering the spinal roots and fusing with the outer membrane of the spinal nerves, the epineurium, as the nerves exit the spinal column via the spinal foramina.

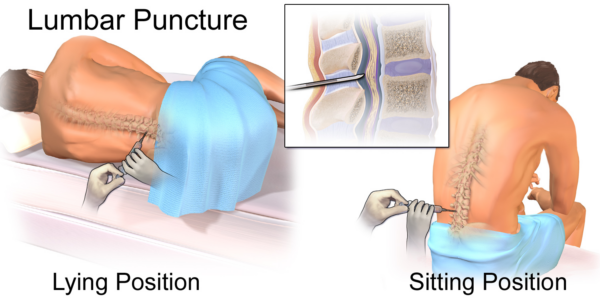

Clinical relevance: Lumbar puncture (LP)

A lumbar puncture is an invasive test designed to access the epidural or subarachnoid space in the lower spinal canal.

Indications for an LP include CSF analysis (e.g. infection, autoimmune disease) when a sample is obtained from the subarachnoid space as well as to administer drugs such as in epidural analgesia.

Relative and absolute contraindications to performing an LP can include raised intracranial pressure (ICP), anticoagulants, clotting disorders, spinal abscesses, acute spinal trauma and congenital spinal deformity.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics OSCE guide to performing a lumbar puncture.

Key points

- There are three distinct meningeal layers, the dura, arachnoid and pia mater, that serve key structural and homeostatic functions for the brain.

- Disruption of these functions can cause reversible and irreversible damage to the brain parenchyma.

- Knowledge of the clinically-oriented anatomy of the meninges is essential for all physicians and surgeons.

Reviewer

Dr Ian Hubbard

Teaching Fellow – MBBS Biomedical Science

Editor

Arunachalam Soma

References

Text references

- Geeky Medics. Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Interpretation. Published in 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Geeky Medics. Lumbar Puncture (LP) – OSCE Guide. Published in 2018. Available from:[LINK]

- Snell, Richard S. Clinical neuroanatomy. Published in 2009. Available from: [LINK]

- Agarwal, Nitin. Neurosurgery Fundamentals. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

Image references

- Frank Gaillard. Layers of the scalp and meninges. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Wikimedia Commons. Falxcerebri. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Flickr. The compartments of the intracranial space with all dural reflections shown. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Notes for Weekly Courses. Epidural haematoma. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Wikimedia Commons. Subdural haematoma caused by trauma. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Wikimedia Commons. An illustration of the different types of a brain haemorrhage. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Wikimedia Commons. Illustration of the artery to trigeminal nerve ganglion (artery of Qureshi) courses demonstrating origin from the extracranial middle meningeal artery. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Flickr. Cerebral veins and sinuses. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Wikimedia Commons. CT image of a subarachnoid haemorrhage. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Wikimedia Commons. Common sites (intracranial) of saccular aneurysms (treated with flow diverter). Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Wikimedia commons. The termination of the spinal cord proper, the cauda equina and filum terminalis. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Wikimedia Commons. Lumbar puncture. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]