- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

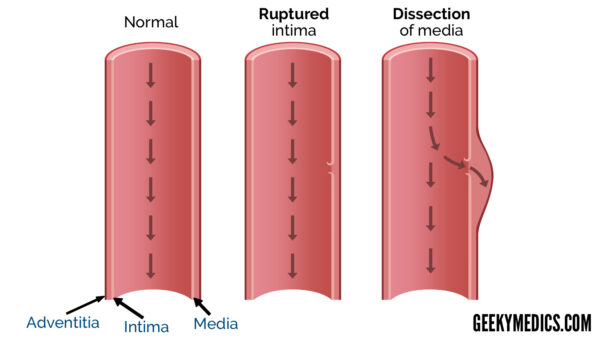

Aortic dissection describes a tear in the intimal layer of the aortic wall, allowing blood to flow between the intima and media, creating a false lumen.1

Acute aortic dissection (AAD) has an annual incidence of 3-4 cases per 100,000 in the United Kingdom, making it the most common emergency affecting the aorta.1,2

AAD can be a catastrophic event with a high mortality rate.3

Aetiology

Anatomy

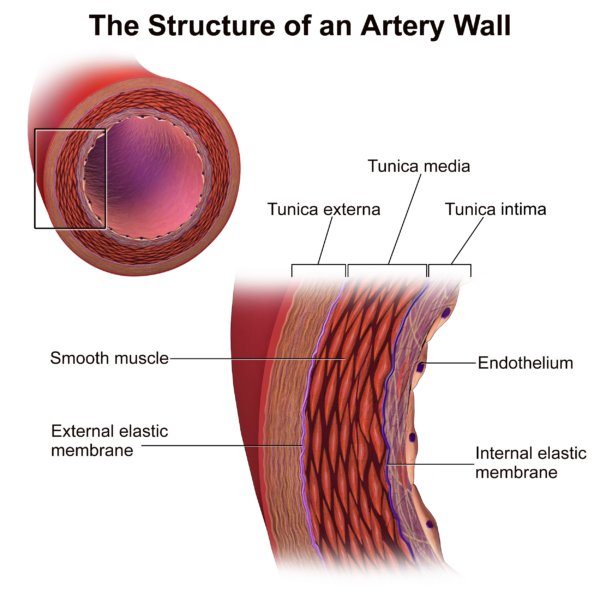

The aortic wall consists of three layers: the intima, media, and adventitia (Figure 1).

Aortic dissection describes a tear in the intimal layer of the aortic wall, allowing blood to flow in the intima-media space, creating a false lumen.

The most commonplace for the initial tear to occur is in the ascending aorta.3

Pathophysiology

The normal arterial lumen lined by intima is called the true lumen, and the blood-filled channel in the media is termed the false lumen.3 The true lumen will often become smaller due to compression by the blood flowing into the false lumen.6

Aortic dissection can propagate longitudinally along the aorta either anterograde (towards the iliac arteries) and/or retrograde (back towards the aortic valve).

Propagation of the dissection can cause branch occlusion (either static or dynamic) and ischaemia of the affected arterial territory. This may be referred to as aortic dissection with end-organ malperfusion.3

Proximal dissections can progress to the aortic valve root and cause cardiac tamponade, acute aortic regurgitation, and/or aortic rupture.3

Risk factors

Risk factors for aortic dissection include:3,4,7,8

- Male sex

- Age 50-70 years

- Hypertension: the most commonly identified risk factor

- Connective tissue disorders, including Marfan’s syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Abrupt, transient, severe increase in blood pressure: may be related to emotional stress, pain, cocaine/amphetamine use or heavy lifting.

- Atherosclerotic disease

- Pre-existing aortic aneurysm

- Bicuspid aortic valve or coarctation of the aorta

- Iatrogenic: aortic instrumentation or surgery including percutaneous stenting or catheter insertion

Clinical features

History

The diagnosis of aortic dissection can be challenging due to an often-vague clinical presentation and the multitude of different presentations of the disease.2,4,7

The characteristic presentation of AAD is severe sudden onset chest or inter-scapular back pain, classically described as sharp, ripping, or tearing in nature.9 This pain commonly settles spontaneously, creating the false impression that there is nothing seriously wrong with the patient.7

Around 10% of AAD cases present without pain, and they are sometimes found incidentally via imaging for another indication.3,7

Less typical presenting features include abdominal or flank pain and symptoms related to end-organ malperfusion. AAD can also present with cardiovascular collapse caused by acute aortic rupture.

Atypical presentations of acute aortic dissection

Atypical presentations of acute aortic dissection related to end-organ malperfusion include:3,7

- Neurological deficits: such as syncope, seizure, limb paraesthesia or paraplegia

- Limb pain and/or pallor: due to acute limb ischaemia

- Flank pain and/or reduced urine output: due to renal artery involvement

- Abdominal pain: due to compromised gut perfusion (e.g. mesenteric ischaemia)

Clinical examination

A full cardiovascular and abdominal examination should be performed in suspected cases of AAD. It is important to measure blood pressure in both upper limbs if AAD is suspected.

Typical clinical findings in AAD include:3,7,9

- Pulse deficit* or asymmetric blood pressure readings: classically associated with type A (see diagnosis section) aortic dissection (secondary to compression/occlusion of the left subclavian artery), but present in only 20% of cases.7

- Hypertension: very common and often extreme. Due to pre-existing hypertensive condition and/or increased sympathetic activation.

- Hypotension: may be spurious due to branch vessel occlusion or be a sign of cardiac tamponade, aortic regurgitation, hypovolaemia (from aortic rupture), or neurogenic shock.

- Tachycardia

- Diastolic murmur: from aortic regurgitation.

- Pulsus paradoxus, muffled heart sounds, or distended neck veins: suggesting cardiac tamponade.

- Decreased breath sounds: haemothorax

* a difference of >20 mmHg in blood pressure between limbs, a weaker or absent central or peripheral pulse compared to the contralateral side, or a palpable thrill/audible bruit over pulses.7,8

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses of aortic dissection include the following conditions:3,4,9

- Acute coronary syndrome: classically crushing and central chest pain, with signs of cardiac ischaemia on ECG and/or raised troponin levels

- Cardiac tamponade without dissection

- Pericarditis

- Spontaneous pneumothorax

- Pulmonary embolism

- Oesophageal rupture

- Musculoskeletal pain

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- ECG: to assess for any evidence of myocardial ischaemia. Ischaemic changes are common in the context of AAD and may indicate coronary involvement.7,8

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:8,9

- FBC, U&Es, LFTs, and coagulation screen

- Arterial blood gas (including lactate): elevated lactate might indicate potential tissue ischaemia

- Group and save and crossmatch (if concerns over bleeding)

- Troponin: may be elevated if dissection causes myocardial ischaemia

- D-dimer: a negative D-dimer indicates that dissection is very unlikely (however it is not sufficient to exclude aortic dissection).

Various biomarkers (e.g. smooth muscle myosin heavy chain) are currently being considered for assessing patients with suspected aortic dissection, however, none are currently part of routine practice.10

Imaging investigations

Imaging is essential to confirm the diagnosis of aortic dissection.6

In modern practice, most patients will undergo an urgent CT angiogram (CTA) of the whole aorta as an initial investigation meaning a plain chest X-ray is not required. However, being aware of X-ray findings is important in the event of an asymptomatic dissection.

Chest X-ray findings of aortic dissection

Chest X-ray findings of AAD include:6

- Widened mediastinum (>8cm): classic finding, but only present in approximately 60% of cases

- Double or irregular aortic contour: occurs in 50% of cases

- Inward displacement of atherosclerotic calcification

- Pleural effusion or haemothorax: indicative of dissection rupture

Note that the chest X-ray is normal in around 10 – 15% of patients with AAD.7

Cross-sectional imaging

CT angiogram (CTA) whole aorta is the investigation of choice as it can confirm the diagnosis and classify the dissection, as well as assessing for distal complications and assisting in surgical planning. Sensitivity and specificity are reported at almost 100% for acute aortic dissection.

However, CTA is not 100% sensitive in detecting features of end-organ malperfusion, especially if the vessel occlusion is dynamic (meaning the dissection flap moves during the cardiac cycle).

History and clinical examination, alongside serial blood markers, are important in ongoing assessment for end-organ malperfusion. There should be a low threshold for repeat CTA if any concerns arise.

Voltage-gated CT (where available) offers superior resolution, which is important in both the ascending aorta and arch of the aorta.8

CT angiogram findings of aortic dissection

Important findings of AAD on CTA include:3,6,11

- Double lumen (true and false lumens) thus confirming the diagnosis of AAD

- The entry tear (where the dissection begins)

- Any evidence of aortic dilatation (aneurysmal change)

- Evidence of end-organ malperfusion (for example non-enhancing kidney)

- Features of acute rupture (including extravasation of contrast or haemothorax)

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) also has excellent sensitivity and specificity, however, its use in the emergency context is limited by its availability, and difficulties in accessing and monitoring the patient during the procedure.9

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) can be used to assess for suspected aortic dissection, but transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) is more sensitive and specific.7

TOE can be used to assess for involvement of the ascending aorta, pericardial effusion, and aortic regurgitation7 However, TOE is more invasive than TTE and requires specialist expertise which limits its availability.7,9

Diagnosis

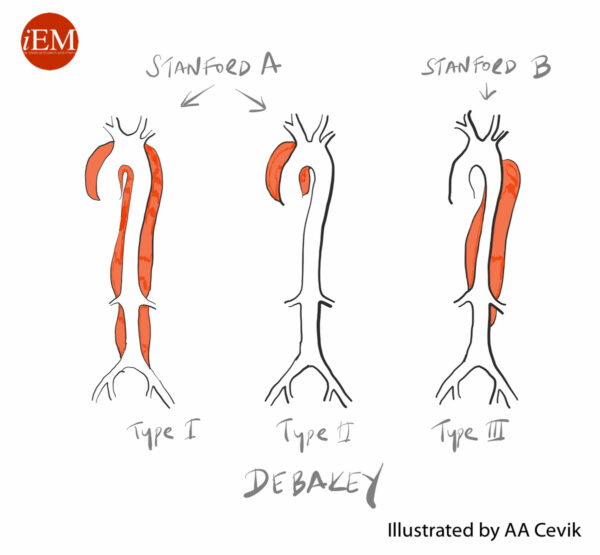

Aortic dissections are usually classified using the Stanford classification. Other classification systems, such as the DeBakey Classification, are less commonly used.6,11

Stanford classification

- Type A: dissection involves the ascending aorta with or without involvement of the arch and descending aorta. Accounts for 60-70% of cases.

- Type B (TBAD): Involves only the descending aorta (distal to the left subclavian artery) and/or abdominal aorta. Accounts for 30-40% of cases

DeBakey classification

- Type 1: intimal tear originates in the ascending aorta and involves the ascending aorta and aortic arch, and variable amounts of the descending aorta.

- Type 2: dissection is confined to the ascending aorta.

- Type 3: intimal tear sited in the descending aorta, distal to the left subclavian artery. Further classified as Type IIIa (affected region is confined above the diaphragm) or Type IIIb (affected region extends below the level of the diaphragm)

Management

Initial management

ABCDE assessment

All AAD cases require an urgent assessment using an ABCDE approach:4

- Priorities for initial management include high-flow oxygen, intravenous (IV) access (ideally two wide-bore IV cannulas), continuous observations, and invasive monitoring (including an arterial line, central venous catheter, and urinary catheter).3,9

- Senior support should be sought from anaesthetics/critical care, cardiothoracic or vascular surgery, and interventional radiology

- If aortic dissection is confirmed, the patient should be discussed urgently with the on-call vascular or cardiothoracic team, and urgent transfer to an appropriate centre arranged.4

Adequate analgesia should be a key early priority but is commonly forgotten (especially during exams). Strong IV opiate analgesia will usually be required. Analgesia can also decrease sympathetic tone and facilitate blood pressure control.3,8

Blood pressure control

Patients with hypertension require active management of blood pressure to rapidly lower the systolic BP, pulse pressure, and pulse rate to minimise the stress of the dissection and limit further propagation. 4,7

The target heart rate is 60-80 bpm and target systolic BP is 100-120 mmHg:4,7,9

- Intravenous beta-blocker infusion (such as labetalol) is the first-line agent

- Second-line agents are IV calcium channel blockers (such as nicardipine or non-dihydropyridine agents)

- IV nitrate infusion or vasodilators (such as sodium nitroprusside) are used in cases of refractory hypertension

- To facilitate control of blood pressure with IV agents, an arterial line must be placed

Surgical management

Subsequent surgical management depends upon the classification of AAD:

- Type A dissections require open surgery to prevent aortic rupture and generally carry a worse prognosis than Type B dissections.4

- Type B dissections (TBAD) are usually managed medically, with endovascular intervention indicated for complicated dissections.7

Type A management

Type A aortic dissections carry a high mortality if managed medically due to the risk of aortic rupture into the pericardium.7 Cases should be discussed urgently with a cardiac or vascular surgeon for consideration of urgent surgical repair.4

Surgical management involves removal of the ascending aorta with or without the aortic arch and replacement with a synthetic graft. If the dissection has damaged the aortic valve, this will also require repair or replacement.1 Branches of the aortic arch involved in the dissection may require reimplantation into the graft.4

Type B management

TBAD is traditionally described as acute (≤ 14 days) or chronic (> 14 days).4

However, more recent classifications include the following groups: hyperacute (<24 hours), acute (24 hours – 14 days), subacute (2 weeks to 3 months) and chronic (>3 months). This has relevance when deciding upon surgical management.

Complicated type B dissections

Complicated TBAD is defined by the presence of any of the following complications: aortic rupture, impending rupture or rapidly expanding aortic diameter, malperfusion due to branch vessel occlusion or aortic lumen compression, ongoing pain, and refractory hypertension.1,4,8

Intervention is almost exclusively with endovascular stent graft placement, sometimes known as TEVAR (thoracic endovascular aortic repair).8 However, a hybrid approach is commonly used to reperfuse any vessels covered by endovascular stents.

The aim of endovascular management is to stent and occlude the proximal entry tear. This promotes false lumen thrombosis and aortic remodelling.8

Surgical or interventional management in the hyperacute phase (<24 hours) is reserved for either acute aortic rupture or malperfusion. Other complications as listed above usually require intervention in the acute period (24 hours – 14 days).

Aortic rupture is a vascular emergency, urgent endovascular intervention is indicated to cover the rupture or tear with an endovascular stent graft to prevent further bleeding.

Branch vessel occlusion can usually be managed by covering the proximal entry tear and restoring true lumen flow. Occasionally, manoeuvres such as additional endovascular stents or balloon fenestration are required.8

Uncomplicated type B dissections

Patients with uncomplicated TBAD are usually managed medically in the initial period, with close blood pressure control and adequate analgesia.1,8 Serial imaging with CTA is suggested to monitor for the development of any complications.

However, the long-term management of uncomplicated TBAD is debated, as medical therapy alone has a poor-long term outcome.13

Increasingly, it is being accepted that endovascular intervention may prevent late aortic-related mortality.14-16

Intervention is usually performed in the subacute phase (2 weeks to 3 months), as this is associated with fewer complications (namely retrograde type A dissection). However, it is important to consider the risks and benefits of intervention on an individual basis before reaching a decision.

If the patient is not suitable for intervention, follow-up with CT surveillance is advised:

- For TBAD managed medically, CT scan at 2-3 days/1 week/1 month is advised. Additional scans at 6 and 12 months may be indicated, followed by ongoing annual surveillance.

- For TBAD managed with TEVAR, CT surveillance at 4-weeks, followed by annual scans, is advised.

Consideration should also be given to the aetiology of the dissection. Ongoing medical management of blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors is advised.

In younger patients, the involvement of an appropriate specialist physician may be necessary for blood pressure management. In addition, a careful family history and consideration of referral for genetic screening is important in patients with a suspected underlying connective tissue disorder.

Complications

One of the primary complications of aortic dissection is aortic rupture.2,7 Rupture is often a catastrophic event, with a quoted mortality of 80%.2 Rupture may be indicated by hypotension, syncope, haemothorax, cardiac tamponade, mediastinal haematoma, or retroperitoneal haemorrhage.7,9

Other complications that arise depend on the site and propagation of the dissection, in particular, the branch vessels affected. Complications that can occur include:3,6

- Acute aortic regurgitation

- Myocardial ischaemia

- Cardiac tamponade

- Aneurysmal dilatation

- Ischaemic stroke or paraplegia

- Acute limb ischaemia

- Renal failure

- Bowel ischaemia

Prognosis

Overall aortic dissection carries a high mortality of 10-35%.6

The highest mortality period is within the first 10 days, and 20% of patients die before reaching hospital.3,4

Early diagnosis, adequate blood pressure control, and early surgical/endovascular intervention dramatically improve the prognosis.2,4

Key points

- Aortic dissection is the most common emergency affecting the aorta and is associated with significant mortality.

- Aortic dissection describes a tear in the intimal layer of the aortic wall causing the formation of a false lumen.

- Important risk factors are male gender, age 50-70 years, hypertension, and connective tissue disease.

- Patients classically present with a tearing chest pain, radiating through to the back.

- Important examination findings include hypertension and pulse deficits/asymmetric blood pressure readings.

- CTA is the gold-standard investigation to diagnose and classify aortic dissection.

- Type A dissections require urgent surgical management.

- Type B dissection is primarily managed medically although evidence suggests endovascular intervention may be warranted to prevent late complications such as aortic rupture.

Reviewers

Mr Craig Nesbitt

Consultant Vascular Surgeon

Northern Vascular Centre, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle Upon Tyne

Mr James McCaslin

Consultant Vascular Surgeon

Northern Vascular Centre, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle Upon Tyne

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Thrumurthy SG, Karthikesalingam A, Patterson BO, Holt PJE, Thompson MM. The diagnosis and management of aortic dissection. BMJ. 2012;344:d8290.

- Knott D. Aortic Dissection. 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Levy D, Goyal A, Grigorova Y, Farci F, K. Le J. Aortic Dissection. Stat Pearls. Treasure Island (FL): Stat Pearls Publishing; 2021.

- Blausen staff. The Structure of An Artery Wall. License: [CC BY]

- GeekyMedics. Aortic dissection. All rights reserved.

- Hacking APC, Gaillard APF. Aortic Dissection. 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Cumberbatch GLA. Aortic Dissection – RCEMLearning. 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Hicks CW, Black III JH. Aortic Dissection. 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Nickson C. Acute Aortic Dissection. 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Mussa FF, Horton JD, Moridzadeh R, Nicholson J, Trimarchi S, Eagle KA. Acute Aortic Dissection and Intramural Hematoma. JAMA. 2016;316:754.

- Mcmahon MA, Squirrell CA. Multidetector CT of Aortic Dissection: A Pictorial Review. RadioGraphics. 2010;30:445-460.

- Cevik A. Aortic Dissection Stanford and De Bakey. License: [CC BY-NC-SA]

- Durham CA, Cambria RP, Wang LJ, Ergul EA, Aranson NJ, Patel VI, Conrad MF. The natural history of medically managed acute type B aortic dissection. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2015;61:1192-1199.

- Brunkwall J, Kasprzak P, Verhoeven E, Heijmen R, Taylor P, Alric P, Canaud L, Janotta M, Raithel D, Malina M, et al. Endovascular Repair of Acute Uncomplicated Aortic Type B Dissection Promotes Aortic Remodelling: 1 Year Results of the ADSORB Trial. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2014;48:285-291.

- Nienaber CA, Kische S, Rousseau H, Eggebrecht H, Rehders TC, Kundt G, Glass A, Scheinert D, Czerny M, Kleinfeldt T, et al. Endovascular Repair of Type B Aortic Dissection. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2013;6:407-416.

- VIRTUE Investigators. Mid-term Outcomes and Aortic Remodelling After Thoracic Endovascular Repair for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Aortic Dissection: The VIRTUE Registry. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2014;48:363-371.