- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

A stone, or calculus, is an abnormal deposit of solid material that forms within an organ. Stones can affect several body systems, including the hepatobiliary system, urinary tract and salivary glands.

Gallstones (cholelithiasis) occur when abnormal deposits of solid material form within the biliary tree.

Gallstones most commonly occur in the gallbladder (cholecystolithiasis) but are also sometimes found in the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis), pancreatic duct (pancreatolithiasis) or hepatic ducts (hepatolithiasis).

Gallstones are extremely common and can range in size from a grain of sand to a large pebble – the biggest one ever recorded was a small boulder weighing more than 6kg! In most cases, they never cause any problems. However, if a stone gets stuck somewhere, it can lead to a spectrum of complications ranging from transient abdominal pain to overwhelming biliary sepsis.

This article will cover the anatomy and physiology of the gallbladder, the aetiology of gallstones, and the clinical features and management of their acute complications, including biliary colic, acute cholecystitis, obstructive jaundice, acute cholangitis, gallstone pancreatitis and gallstone ileus.

We will also briefly discuss chronic complications of gallstones and relevant differential diagnoses.

Anatomy

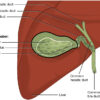

The gallbladder

The gallbladder is a small fluid-filled sac located in the gallbladder fossa beneath the right lobe of the liver. It is shaped like a pear, with a narrow neck at the top, a broader body and a rounded fundus at the bottom. It is usually about 7-10cm long but can vary considerably in size.

The gallbladder neck often contains a mucosal bulge or fold called Hartmann’s pouch, a common place for gallstones to get stuck. The neck and body rest snugly against the liver on a layer of connective tissue, which is known as the gallbladder bed or cystic plate. The fundus usually peeps out from underneath the liver edge and sits close to the anterior abdominal wall near the tip of the ninth rib in the mid-clavicular line.

The gallbladder neck transitions into a short cystic duct (CD), which then joins with the common hepatic duct (CHD) to form the common bile duct (CBD). In most people, the lining of the cystic duct contains numerous spiral-shaped folds known as the valves of Heister.

The gallbladder receives its arterial blood supply from the cystic artery, a branch of the right hepatic artery. Its venous drainage follows multiple small cystic veins into the right portal vein. There is also a lymph node sitting on top of the cystic artery, which is inconsistently called either the cystic node, Lund’s node, Calot’s node or Mascagni’s node.

Clinical relevance – laparoscopic cholecystectomy

The cystic artery lies within the hepatocystic triangle, an essential landmark for achieving the “critical view of safety” during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The triangle is formed by the cystic duct laterally, the common hepatic duct medially, and the inferior edge of the liver superiorly.

Before clipping the cystic artery and cystic duct, the gallbladder neck must be mobilised from the cystic plate, and the hepatocystic triangle must be completely cleared of tissue to allow the surgeon to visually confirm the two structures they intend to cut are entering the gallbladder and not the liver.

This standardised approach minimises the risk of accidentally dividing the common bile duct or right hepatic artery, which would be disastrous.

The hepatocystic triangle is often incorrectly referred to as Calot’s triangle. This is actually a smaller triangle created by the cystic duct, common hepatic duct and cystic artery.

Common bile duct

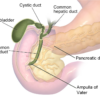

The common bile duct is about 8cm long. Proximally, it forms part of the portal triad along with the portal vein and proper hepatic artery. It sits in front of the vein and lateral to the artery. These three important structures travel downwards within the hepatoduodenal ligament, which is the thickened free edge of the lesser omentum lying in front of the opening of the lesser sac.

The CBD then passes behind the first part of the duodenum and the head of the pancreas. Distally, it joins with the main pancreatic duct (PD) to form a dilated common channel known as the ampulla of Vater before draining into the second part of the duodenum through the major duodenal papilla.

The ampulla of Vater is surrounded by a circular valve of smooth muscle known as the sphincter of Oddi, which controls the flow of bile and pancreatic juice into the bowel lumen and prevents reflux of duodenal contents into the biliary system.

Function of the gallbladder

The gallbladder has one job: to concentrate and store bile produced by the liver and release it when required. Bile is a dark green alkaline fluid which contains water, bilirubin, bile acids, cholesterol, phospholipids and electrolytes. It neutralises gastric acid and emulsifies fats to facilitate their digestion and absorption.

Bile is synthesised by hepatocytes and reaches the gallbladder through a network of bile canaliculi which drain into the hepatic ducts and the cystic duct. Some people also have small aberrant subvesical ducts (previously known as Luschka ducts), which drain directly across the gallbladder bed from the right lobe of the liver. These are often cut during cholecystectomy and are a common source of postoperative bile leaks.

When fatty food enters the duodenum, its enteroendocrine I-cells release a hormone called cholecystokinin. This stimulates contraction of the gallbladder and relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi, allowing bile to flow into the duodenal lumen.

The gallbladder holds around 50ml of fluid but normally empties completely after a meal. This is why it is important to inform patients to fast before an ultrasound scan, as you are unlikely to get any useful diagnostic information from a deflated gallbladder.

Aetiology

Causes of gallstones

At least 10-15% of people in Western countries will develop gallstones at some point in their lives, compared with less than 5% of people in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Cholecystectomy is one of the most common general surgical operations in the UK, with around 70,000 performed yearly. Gallstones are twice as common in women, and the incidence increases with age, peaking at age 70-79.

Stones are formed by the precipitation of solutes from a body fluid, producing sediment aggregating into a mass. This process is triggered by a combination of three factors (the three “S”s):

Supersaturation

An increase in the concentration of one or more solutes increases the likelihood of precipitation. This may be due to excessive amounts of one component of bile, such as cholesterol or bilirubin (see below), or generalised overconcentration of all bile components (e.g. due to dehydration).

Stasis

Stagnant body fluids are more likely to allow sedimentation and stone formation. Bile stasis (or cholestasis) often results from mechanical obstruction by stents, strictures, tumours, or parasitic infections such as Clonorchis sinensis or Opisthorcis vivirensis (also known as liver flukes).

Cholestasis can also be caused by functional impairment of bile flow. Both oestrogen and progesterone can impair gallbladder emptying, meaning that female gender, pregnancy, the oral contraceptive pill and hormone replacement therapy all increase the risk of gallstones.

Major gastric surgery may injure vagus nerve branches and/or reduce cholecystokinin secretion, resulting in decreased stimulation of gallbladder contractions. Diabetic neuropathy and spinal cord injuries can cause neurogenic gallbladder stasis. Somatostatin analogues and GLP-1 inhibitors also induce cholestasis.

Sepsis

Some anaerobic bacteria possess enzymes which deconjugate bilirubin and produce a bile pigment sludge. These are usually Gram-negative organisms such as E. coli, Klebsiella and Enterobacter. The antibiotic ceftriaxone can also form sludge by binding to and precipitating calcium salts.

Types of gallstones

There are three main types of gallstones, which have different aetiologies and risk factors:

- ~80% cholesterol and mixed stones

- ~15% black pigment stones

- ~5% brown pigment stones

Cholesterol and mixed stones

Cholesterol stones contain >70% cholesterol. They are smooth and spherical or ovoid. They float in water and are large and often solitary. They are rarely visible on X-rays as they contain little calcium.

Mixed stones contain 30-70% cholesterol with varying amounts of bile pigments, calcium salts and other things. They are by far the most common type of gallstones and are usually cholesterol stones which have accumulated layers of other substances over time. They sink in water, tend to be multiple and have flattened faceted surfaces. As they contain some calcium, around 20% are radio-opaque and visible on X-rays.

Cholesterol stones are caused by stasis and supersaturation of cholesterol. They are extremely common in Western populations.

The risk factors for cholesterol stones are classically memorised using the five “F”s: female, forty, fair, fat and fertile. These cover the general risk factors for gallstones (gender, increasing age and ethnicity) and factors causing increased cholesterol concentration, such as obesity, a high-fat diet, physical inactivity, and oestrogen exposure due to contraception or pregnancy. Family history is another important risk factor. Rapid weight loss (e.g. following bariatric surgery) also increases cholesterol levels within the bile.

Black pigment stones

These contain <30% cholesterol and are mostly composed of polymerised calcium bilirubinate, calcium phosphate and calcium carbonate. They are small, irregular, hard and brittle, often too many to count. As they contain lots of calcium, up to 75% of black pigment stones are visible on X-rays.

Black pigment stones are caused by stasis and supersaturation of bilirubin. They are typically associated with chronic haemolysis, such as sickle cell disease, thalassaemia, spherocytosis, malaria, hypersplenism and prosthetic heart valves. Other conditions resulting in excessive concentrations of bile pigments include Gilbert’s syndrome, liver cirrhosis, total parenteral nutrition, and bile salt malabsorption due to Crohn’s disease, terminal ileal resection, chronic pancreatitis or cystic fibrosis.

Brown pigment stones

These contain <30% cholesterol and mainly consist of unpolymerised calcium bilirubinate and fatty acid salts. They are soft, greasy, and clay-like. Unlike other types, they usually form within the bile ducts rather than the gallbladder. Although they contain calcium, they are rarely visible on X-rays because of their molecular structure.

Brown pigment stones are caused by stasis and chronic bacterial infection. They are much more common in Asian populations. Foreign bodies such as biliary stents and parasitic worms can provide a nidus for infection and sediment aggregation. Due to the presence of bacteria, they carry a high risk of infective complications such as cholangitis and biliary sepsis.

Uncomplicated gallstones

Gallstones are asymptomatic in over 80% of patients and are often picked up incidentally on imaging tests performed to investigate abdominal pain or abnormal blood results. Don’t assume gallstones are causing a patient’s problem just because they appear on imaging!

Longstanding uncomplicated gallstones may cause mild symptoms. These include intermittent upper abdominal discomfort, indigestion, nausea, bloating, excessive flatulence, intolerance of fatty foods, or an altered bowel habit. Patients often attribute these symptoms to a different problem, such as irritable bowel syndrome.

Complicated gallstones

Around 20% of people with gallstones will eventually develop complications. Complicated gallstones tend to cause more distressing acute symptoms.

Complications of gallstones are generally caused by a stone getting stuck somewhere. Telling them apart ultimately boils down to three key factors:

- where the stone gets stuck

- how long for

- whether it causes any inflammation or infection.

Gallstones stuck in the gallbladder neck or cystic duct may lead to:

- Acute complications: biliary colic, acute cholecystitis, Mirizzi syndrome

- Chronic complications: gallbladder mucocele, chronic cholecystitis, porcelain gallbladder, gallbladder cancer

Gallstones stuck in the common bile duct may lead to:

- Acute complications: obstructive jaundice, acute cholangitis, gallstone pancreatitis

- Chronic complications: cholangiocarcinoma

Gallstones stuck in the bowel may lead to:

- Acute complications: gallstone ileus, Bouveret’s syndrome

- Chronic complications: cholecystoenteric fistula

Biliary colic

Biliary colic is a sudden painful spasm of the gallbladder wall triggered by a gallstone. This term can also describe gallstone-related spasms of the cystic duct or common bile duct.

Biliary colic is the most common acute complication of gallstones. While not life-threatening, it can be very painful, and recurrent attacks can have a major impact on quality of life.

Aetiology

Biliary colic usually occurs when a stone gets stuck in the gallbladder neck or the cystic duct, obstructing bile flow.

The gallbladder contracts to dislodge the stone, and its wall stretches and distends, causing visceral pain. Depending on its size, the stone will either pass into the common bile duct, drop back into the gallbladder, or become completely impacted and remain stuck.

Impacted stones may progress to cause acute cholecystitis, Mirizzi syndrome or a mucocoele.

Clinical features

Typical symptoms of biliary colic include:

- Sudden onset and severe RUQ/epigastric pain (may radiate to the lower chest, back or right shoulder)

- Autonomic symptoms: nausea, vomiting, sweating, palpitations

An episode of isolated biliary colic lasts about 6 hours and subsides once the stone is dislodged.

Unlike intestinal colic, which comes in discrete sharp spasms, biliary colic tends to be dull and constant, with occasional waves of more intense pain. Patients do not have fevers.

Attacks are often precipitated by eating fatty or spicy foods, with the pain starting a few hours afterwards or waking the patient up overnight. They often report writhing around and being unable to get comfortable. This is reassuring, as it indicates a lack of peritoneal irritation: peritoneal pain is worse on movement and makes people want to lie still.

Patients with biliary colic are generally systemically well with normal or near-normal observations. They usually have RUQ tenderness and may have some voluntary guarding but do not have any peritonism.

Investigations

Patients should undergo the standard initial investigations for acute abdominal pain. Remember that problems above the diaphragm can also present with upper abdominal pain, so consider acute coronary syndromes, aortic dissection, pneumonia, or pulmonary embolism.

In most cases of biliary colic, inflammatory markers and liver function tests will be normal.

Ultrasound is the gold standard imaging test for gallstones. In biliary colic, this will show gallstones in a thin-walled gallbladder.

It is important to reiterate that uncomplicated gallstones could still be an incidental finding. If the patient’s symptoms don’t quite fit with biliary colic, you may need to consider additional tests (e.g. CT scan or an OGD) to assess for other causes.

Management

Biliary colic is a self-limiting condition, and most cases are managed with oral analgesia and ambulatory care follow-up for any necessary scans. Patients can eat if they want to, but sticking to clear fluids until their symptoms have eased will reduce the likelihood of painful gallbladder spasms.

Biliary colic is a warning sign for troublesome gallstones. Within a year of their first episode, 50% of people will experience a recurrent attack, and 1-3% will develop more serious acute complications.

Once the diagnosis has been confirmed, patients should see a surgeon to discuss having an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy to relieve their symptoms and prevent complications. This is usually performed as a day case operation and is very safe, with a mortality of less than 0.5%.

Patients with mild symptoms and a single episode of biliary colic may wish to see how things go for a while before deciding what to do. Lifestyle changes such as a low-fat diet, gradual weight loss and avoidance of trigger foods can reduce symptoms, but surgery is the only way to get rid of the stones.

Patients with severe pain often require admission to hospital for symptom control. They may be offered an emergency cholecystectomy, especially if they have had multiple attacks in a short period.

Acute cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis is the acute inflammation of the gallbladder. More than 90% of cases are associated with gallstones. This is also known as calculous cholecystitis.

Acute cholecystitis is the second most common acute complication of gallstones. It affects up to 20% of patients with symptomatic gallstones and is responsible for around 5% of all hospital admissions with acute abdominal pain.

Aetiology

Acute calculous cholecystitis occurs when a stone gets stuck in the neck of the gallbladder or the cystic duct and becomes completely impacted there, causing total obstruction of bile flow.

Prolonged bile stasis leads to chemical irritation of the gallbladder, which triggers an acute inflammatory response with gallbladder wall oedema. In at least a third of cases, a superimposed bacterial infection also develops within the stagnant bile.

Clinical features

Acute cholecystitis normally begins as an attack of biliary colic, but the pain lasts more than 6 hours and worsens. As the parietal peritoneum around the gallbladder becomes inflamed, the pain becomes sharper and more localised and is exacerbated by movement. Pain radiating to the right shoulder is much more common as the local inflammatory process also irritates the phrenic nerve. Patients usually feel systemically unwell with vomiting and fevers.

On examination, patients often have pyrexia and tachycardia. There is usually severe RUQ tenderness with voluntary guarding or localised peritonism.

Murphy’s sign

Murphy’s sign is a painful inspiratory “catch” during RUQ palpation. When the patient takes a deep breath in, their tender inflamed gallbladder bumps into the examiner’s hand, causing them to jump or flinch. This only occurs in half of cases and is unreliable in older people, so the absence of Murphy’s sign does not rule out acute cholecystitis.

Some patients have a palpable RUQ mass. In most cases, this is not the gallbladder itself but an irregular phlegmon of inflamed omentum sitting over the top of it. A palpably enlarged gallbladder is quite an uncommon finding and is more likely to indicate a mucocoele, gallbladder cancer or progressive obstruction of the common bile duct (Courvoisier’s sign).

Investigations

Patients should undergo the standard initial investigations for acute abdominal pain. In acute cholecystitis, inflammatory markers such as white blood cell count and C-reactive protein are usually raised. Liver function tests may show an elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Jaundice is concerning for CBD stones or Mirizzi syndrome and should be investigated thoroughly before surgical intervention.

Ultrasound usually shows a thick-walled gallbladder (>3mm) with probe tenderness or a sonographic Murphy’s sign. It may also identify impacted gallstones, localised oedema or pericholecystic fluid.

Although ultrasound is the preferred test for acute cholecystitis, it is not always readily available, especially for patients who present to the ED with severe abdominal pain in the middle of the night. In this scenario, a CT scan is often done first to aid decision-making. CT is highly accurate for acute cholecystitis, although it will miss at least 20% of underlying gallstones. It can also rapidly rule out other life-threatening intra-abdominal problems such as haemorrhage, bowel perforation or ischaemia.

Management

Patients with acute cholecystitis almost always require hospital admission. They should receive antibiotics to cover any superimposed infection. Antibiotics can be given either orally or IV, depending on the patient’s clinical condition and local microbiology guidelines.

Patients should be restricted to clear oral fluids as they will likely require surgery. Although most cases of acute cholecystitis will settle with antibiotic therapy, current guidelines recommend an emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy provided the patient is within seven days of symptom onset.

Due to the presence of infection and inflamed friable tissues, emergency cholecystectomy can be more technically challenging than elective surgery. However, it appears to be just as safe. It is also associated with shorter hospital stays and lower overall morbidity, as many patients will become unwell with further acute complications of gallstones whilst waiting for an elective operation.

Patients who are frail or critically unwell can be managed with a percutaneous cholecystostomy. This is an interventional radiology procedure which places a drain into the gallbladder through the skin. It relieves the pressure inside the gallbladder and provides source control for infection.

Complications

There are several important complications of acute cholecystitis to be aware of. These are more common in older men and people with cardiovascular disease or diabetes.

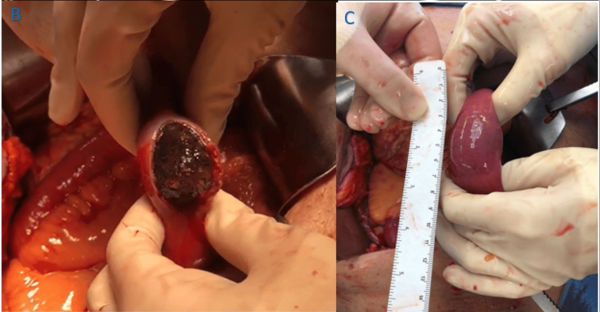

- Gangrenous cholecystitis is the most common complication. It occurs when an inflamed, overdistended gallbladder wall loses its capillary microcirculation and becomes ischaemic and necrotic over several days. In many cases, part of the wall completely breaks down, causing a gallbladder perforation. This will lead to either a pericholecystic abscess or biliary peritonitis, depending on where the hole is and whether or not it gets walled off by the omentum

- A gallbladder empyema (also known as suppurative cholecystitis) occurs when the lumen of an infected gallbladder fills with pus. It is associated with swinging fevers and systemic sepsis.

- Emphysematous cholecystitis is a rare complication which occurs when the gallbladder wall is infected by gas-forming organisms such as E. coli or Clostridium perfringens. It has a very high risk of progression into fulminant gangrene, perforation and severe sepsis, and mortality of around 20%.

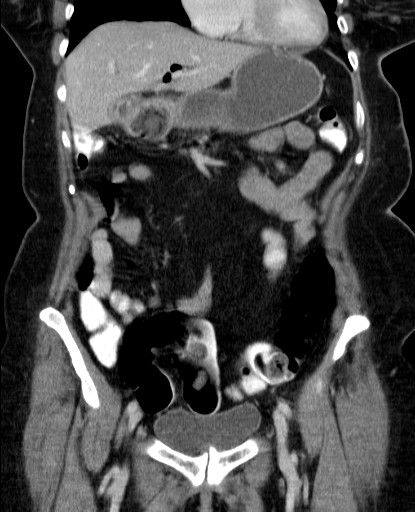

CBD stones and obstructive jaundice

Jaundice (also sometimes called icterus) is the accumulation of excess bile pigments in the tissues secondary to abnormally elevated serum bilirubin levels. This manifests clinically as yellow discolouration of the skin, sclera and mucous membranes.

Obstructive jaundice is caused by a blockage of bile drainage through the biliary system, which may occur from the intrahepatic duct branches to the ampulla of Vater.

Common bile duct stones affect 10-20% of people with symptomatic gallstones. They are also the most common cause of obstructive jaundice.

Aetiology

Obstructive jaundice due to gallstones usually occurs when a stone escapes from the gallbladder and gets stuck in the common bile duct. It can also be caused by de novo CBD stones and by Mirizzi syndrome, which is covered separately later on. This section will focus on jaundice due to CBD stones.

CBD stones are more likely to affect people with smaller gallstones (<1cm in size) as these can fit through the cystic duct.

Clinical features

CBD stones may be asymptomatic, especially in older patients with wider bile ducts. Small stones can also pass spontaneously on their own, resulting in self-limiting episodes of pain with or without jaundice.

Obstructive jaundice presents with yellowing of the skin and eyes, dark urine and pale stools. Many patients also report itchy skin, which often precedes the onset of jaundice.

The jaundice may be painless, but is more likely to be associated with RUQ pain or epigastric pain radiating into the back as the stone passes further along the bile duct. Patients often have associated vomiting and usually feel generally unwell with malaise.

Investigations

Obstructive jaundice can be differentiated from other types of jaundice by the clinical history and liver function tests, which show a cholestatic picture with a markedly raised ALP compared to ALT and AST.

An ultrasound scan usually shows gallstones and a dilated common bile duct. The normal CBD diameter is ≤6mm. However, a CBD of up to 10mm may be considered normal in elderly patients or after a cholecystectomy, provided the patient is otherwise asymptomatic.

A CT scan can help assess for intra-abdominal infection and exclude other causes of jaundice, such as pancreatic cancer. However, it may not be able to identify the stone(s) and is not very good for assessing the anatomy of the biliary tree in detail.

The preferred imaging test for suspected CBD stones is a specially protocolled MRI scan known as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). MRCP is highly accurate and requires no radiation exposure or IV contrast. However, it is often contraindicated in patients with metallic implants and can also be distressing for people with claustrophobia. In this scenario, it is worth asking the radiographer if the patient can go into the scanner feet-first, so their head is not enclosed.

Management

Patients should receive initial treatment for obstructive jaundice, which includes consideration of IV fluid resuscitation and correction of any associated coagulopathy. They will also be grateful if you prescribe anti-itching medications such as chlorphenamine or cholestyramine.

In addition to problems related to their gallstones, patients with CBD stones are at risk of serious complications, including recurrent jaundice, cholangitis and pancreatitis. They require extraction of their CBD stones and removal of their gallbladder. There are two ways of achieving this:

Staged or sequential approach

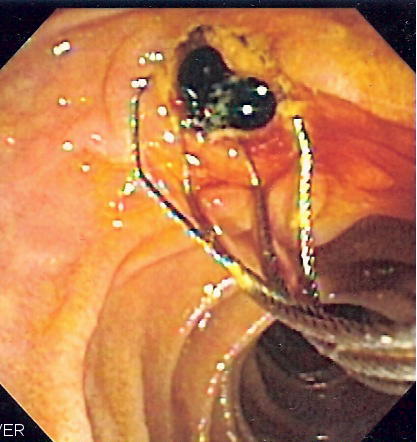

This involves an urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and stone extraction followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy. ERCP is usually performed under sedation in the endoscopy department. It involves using a gastroscope to identify the duodenal papilla, cannulating the common bile duct with a wire, then using a range of instruments to clear the bile duct under fluoroscopy (X-ray) guidance. A temporary plastic stent is often left in afterwards to facilitate bile drainage whilst any inflammation settles.

“One-stop” surgery

This involves an urgent laparoscopic cholecystectomy with common bile duct exploration (CBDE) and intraoperative stone extraction. CBDE involves making an incision in the common bile duct and inserting a choledochoscope to visualise and remove the stone(s). A cholangiogram is then performed to check the duct is completely clear. The hole in the bile duct is repaired with sutures, and a drain is left in the abdomen for a few days.

This approach is hypothetically better as it only involves one procedure, and it avoids the potential additional complications of an ERCP. However, studies have shown no differences in outcomes between the two treatment strategies.

ERCP and CBDE are advanced procedures requiring specialist training and expertise. The preferred approach in each hospital will vary depending upon the skill mix within endoscopy and surgical teams.

Frail patients with significant comorbidities may be offered ERCP alone as a definitive procedure.

Acute cholangitis

Acute cholangitis is caused by an acute bacterial infection within the biliary tree.

Acute cholangitis (ascending cholangitis or biliary sepsis) is the most deadly acute complication of gallstones. It is rare, affecting less than 1% of people with gallstones, but has a mortality of about 10%.

Aetiology

Acute cholangitis is almost always associated with biliary obstruction. It is most commonly caused by a stone getting stuck in the CBD and completely blocking the flow of bile, creating ideal conditions for an opportunistic infection.

The stagnant bile becomes contaminated with gut organisms, predominantly Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli, Klebsiella or Enterobacter. Once established, the infection progresses rapidly, and the bile duct fills up with pus which “ascends” proximally towards the liver.

Cholangitis is also frequently triggered by procedures involving instrumentation of the biliary tree and complicates up to 5% of ERCPs. Other risk factors include strictures, tumours or stents within the bile duct, primary sclerosing cholangitis, liver flukes, smoking, diabetes and immunocompromise.

Clinical features

Acute cholangitis is primarily a clinical diagnosis and should be suspected in any patient with jaundice who “doesn’t look right”.

Many patients also have signs of systemic sepsis, such as tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnoea, a new oxygen requirement, confusion or drowsiness. Hypotension which does not respond to fluid resuscitation is concerning for septic shock, which is associated with mortality rates of over 40%.

Charcot’s triad

Acute cholangitis classically presents with Charcot’s triad, which consists of RUQ pain, jaundice and fever, usually associated with rigors.

However, whilst this triad of symptoms is highly specific, it only occurs in about 40% of patients and cannot be used as a diagnostic tool.

Investigations

Blood tests will show obstructive jaundice and raised inflammatory markers. It is important to look for signs of end-organ dysfunction, such as acute kidney injury, elevated lactate, coagulopathy, or thrombocytopenia, as these are additional hallmarks of sepsis. Remember to take blood cultures.

Ultrasound will show a dilated, thick-walled common bile duct but is not always readily available in an emergency. Many patients with cholangitis are too unstable to spend half an hour inside an MRI scanner, so it may not be appropriate to proceed directly to an MRCP.

Although not the best test for biliary pathology, CT plays an important role in assessing suspected cholangitis as it is fast, safe and can be used to rule out other potential causes of intra-abdominal sepsis. A CT scan will demonstrate biliary dilatation with wall thickening and inflammation around the common bile duct. CT can also locate CBD stones in over 80% of cases.

Management

Patients with suspected cholangitis require immediate treatment for sepsis, including IV fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum IV antibiotics and consideration of the need for escalation to ICU. If you suspect a patient has cholangitis, you must take this seriously and have a very low threshold for involving the critical care team.

The next priority is urgent decompression of the biliary system. In most cases, this involves performing an ERCP as soon as possible, ideally within 24 hours, as mortality increases significantly in patients who wait longer than this.

Some patients are too unwell to undergo endoscopy, and others may have an unsuccessful ERCP. In these cases, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and biliary drainage (PTC / PTBD) is an alternative. This is an interventional radiology procedure which involves using a wire to access a hepatic duct through the skin, and then advancing a drain forwards into the common bile duct.

Surgical drainage is an absolute last resort, as it is associated with very high mortality. Patients who still have their gallbladder should have a cholecystectomy as soon as they are well enough, but many need time to recover first.

Gallstone pancreatitis

Gallstone pancreatitis is the sudden onset of acute inflammation within the pancreas secondary to gallstones.

Gallstone pancreatitis is a common and potentially life-threatening acute complication of gallstones. It affects 1-2% of people with gallstones and is the most common cause of acute pancreatitis.

Aetiology

Gallstone pancreatitis is typically caused by a stone passing through the ampulla of Vater. This causes pressure build-up and stasis of exocrine secretions, including digestive enzymes, within the pancreatic duct and its branches. These enzymes then begin to autodigest the pancreas.

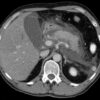

In around 90% of cases the pancreatic tissue injury causes diffuse inflammation and swelling. This is known as interstitial oedematous acute pancreatitis and has a mortality of less than 5%.

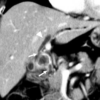

In up to 10% of cases, areas of badly damaged pancreatic tissue lose their blood supply and start to become ischaemic and die. This more serious form is known as necrotising acute pancreatitis and has a mortality of over 15%, which increases to around 40% if it becomes infected later on.

Rarely the autodigestive process eats into the wall of a large blood vessel, causing retroperitoneal bleeding. This is known as haemorrhagic acute pancreatitis and can rapidly progress to shock, exsanguination and sudden death.

In around 75% of cases, the CBD stone passes on its own and only causes transient biliary obstruction. In the remainder, the stone gets stuck at the ampulla, and the patient develops obstructive jaundice.

Gallstone pancreatitis is more likely to affect people with multiple small gallstones <5mm in size, as these can pass through both the cystic duct and the sphincter of Oddi.

Clinical features

Gallstone pancreatitis typically presents with a sudden onset of constant, excruciatingly severe epigastric or upper abdominal pain, which often radiates to the back or shoulders and may be relieved by sitting forwards or curling up into a ball. The pain is usually associated with multiple episodes of vomiting, and patients may also report diarrhoea, fevers and sweats. Some patients have pre-existing symptoms, but pancreatitis is often the first presentation of gallstones.

Patients with acute pancreatitis are usually utterly miserable and look unwell from the end of the bed. They often have fever, tachycardia and tachypnoea, and may also develop hypotension due to dehydration and hypovolaemia.

On abdominal examination, most people have severe upper abdominal tenderness with localised peritonism, and will prefer to lie flat and stay very still.

A proportion of cases of acute pancreatitis will present with generalised abdominal pain and peritonitis. This is one of the reasons surgeons are always so keen to request imaging to establish a diagnosis before operating on people, as performing an unnecessary laparotomy on someone with pancreatitis could cause them considerable harm.

Investigations

Most patients with gallstone pancreatitis will have raised inflammatory markers and abnormal liver function tests with a cholestatic picture. The crucial diagnostic blood test is serum amylase – don’t forget to check this in anyone with acute abdominal pain! As with cholangitis, it’s also important to look for evidence of end-organ dysfunction as this informs disease severity and mortality risk.

The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis requires at least two of the following:

- Abdominal pain consistent with acute pancreatitis

- A serum amylase or lipase more than three times the upper limit of normal. Amylase levels peak within hours after the onset of symptoms and may have already returned to normal if the patient has been unwell for a few days. Lipase is a much better test as it is more sensitive and remains detectable for up to 2 weeks. However, it may not be readily available in all hospitals.

- Characteristic features of acute pancreatitis on cross-sectional imaging (CT or MRI)

Most patients will meet the first two criteria. If you have a patient with a good history but a non-diagnostic amylase, you need to do a CT scan. In someone with a sky-high amylase but an atypical history, you also need to do a CT scan.

Unless they have already had a CT scan which identified gallstones, patients with acute pancreatitis should have an ultrasound scan to assess for gallbladder stones and look at their bile duct. Patients with jaundice or biliary dilatation should also have an MRCP to assess for residual CBD stones. Many surgeons routinely request MRCPs for everyone with acute pancreatitis to avoid missing any stones.

Some patients may have biliary sludge or tiny stones like grains of sand (microlithiasis) which are not visible even on an MRCP. These can be detected using a specialist endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).

Management

Acute pancreatitis should be managed with tailored IV fluid resuscitation and analgesia/antiemetics. It is not an infection and does not require antibiotics unless there is evidence of a co-existing infective process elsewhere. Patients do not need to be kept nil by mouth and should be allowed to eat and drink provided they feel up to it and are not vomiting excessively. Those unable to tolerate sufficient oral intake will require early enteral nutrition via an NG or NJ tube.

More than 80% of cases of acute pancreatitis are relatively mild and settle within a week. Patients with residual CBD stones should undergo ERCP and stone extraction within 72 hours of admission. Gallstone pancreatitis often recurs early. Current guidance, therefore, recommends that patients who are well enough should have a cholecystectomy within 2 weeks, ideally during the same hospital admission.

Around 20% of patients will develop local complications or systemic organ dysfunction, resulting in a more protracted illness and recovery lasting months. Severe, necrotising or complicated gallstone pancreatitis should be referred to a regional pancreatic centre for ongoing specialist management.

Mirizzi syndrome

Mirizzi syndrome occurs when a gallstone impacted in the gallbladder neck or cystic duct obstructs the adjacent common hepatic duct, leading to obstructive jaundice.

Mirizzi syndrome is a very rare complication which affects about 0.1% of people with gallstones. It is named after the Argentinian surgeon Pablo Mirizzi, who also did the first intraoperative cholangiogram.

Aetiology

There are two ways in which a gallbladder stone can obstruct the common hepatic duct:

- Extrinsic compression by the physical bulk of the impacted stone. This is known as type I Mirizzi syndrome and represents around half of cases. It may occur suddenly or develop slowly over time.

- Chronic inflammation and ulceration leads to gradual erosion of the wall of the common hepatic duct and formation of a cholecystocholedochal fistula, which allows part of the stone to pass into the duct and obstruct the lumen directly. This is categorised into types II, III and IV depending on the size of the fistula defect.

Mirizzi syndrome tends to affect people with larger gallstones as these are more likely to become stuck in the gallbladder. It also is more common in people with anatomical variations such as a long or tortuous cystic duct.

Clinical features

Mirizzi syndrome typically presents with a combination of acute cholecystitis and obstructive jaundice. Infection of stagnant bile within the proximal biliary tree may also lead to cholangitis and sepsis.

Mirizzi syndrome is also often found unexpectedly during surgery. This occurs in at least 1% of cholecystectomies and can be highly stressful for the surgeon, as these cases carry a very high risk of bile duct injury. Before listing them for surgery, it is important to thoroughly investigate patients with gallstones who report any previous symptoms of jaundice. This is done to assess for CBD stones, Mirizzi syndrome or evidence of malignancy.

Investigations

An ultrasound scan will show a stone impacted in the gallbladder neck and may identify compression of the common hepatic duct with proximal intrahepatic biliary dilatation. However, the results are often inconclusive, and patients usually require more detailed imaging to establish the diagnosis.

A CT scan is helpful as it can define the level of biliary obstruction, identify any acute inflammation and exclude other causes of obstructive jaundice. The preferred imaging test is an MRCP. This will show the cause and anatomy of the obstruction, although it only detects around 50% of fistula tracts.

The absolute gold standard test is an ERCP, as this can reliably identify and characterise the anatomy of any fistulation present to inform surgical planning. However, diagnostic ERCP is undertaken selectively in clinical practice as it is an invasive test with a risk of serious complications.

Management

Mirizzi syndrome can be anatomically complex and often requires input from a specialist HPB surgeon.

“Simple” cases without a fistula require a cholecystectomy to remove the cause of the biliary obstruction. The underlying inflammatory process usually causes the tissues to become fibrotic and densely stuck together, making it very difficult to safely dissect the fused hepatocystic triangle without damaging any important structures. There is a very high chance of conversion to open surgery. In many cases (e.g. where the anatomy is unclear or the tissues are difficult to dissect), it may be safer to bail out by opening the gallbladder, extracting the stones and performing a subtotal cholecystectomy (leaving part of the gallbladder behind) rather than risking a bile duct injury.

For more complicated cases with a fistula, a cholecystectomy is a major undertaking as it will inevitably uncover a hole in the bile duct which must then be repaired or reconstructed. Small fistula defects are generally managed with primary repair over a T-tube, which decompresses the bile duct and helps reduce stricture formation. If the fistula defect is large or the bile duct is badly damaged, the patient may require a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy to allow bile to drain directly into the small intestine.

Gallstone ileus

Gallstone ileus is a form of intestinal obstruction caused by a large gallstone stuck in the bowel lumen. It’s not actually an ileus: an ileus is a functional disorder caused by decreased or dysfunctional bowel motility, which causes features of bowel obstruction but without a mechanical blockage.

Gallstone ileus is rare: it affects less than 1% of patients with gallstones and accounts for less than 1% of cases of bowel obstruction. It usually occurs in patients who are elderly and frail, and the diagnosis is often missed or delayed. It consequently has a high mortality rate of 20-30%.

Aetiology

Gallstone ileus develops when a large gallstone erodes directly through the gallbladder wall and into the adjacent gastrointestinal tract, creating a cholecystoenteric fistula.

As this process occurs very slowly, the body’s inflammatory response has time to seal the area around the fistula to prevent bile leakage or peritonitis. Gallstones can then pass through the fistula tract into the bowel lumen. Most stones are small and cause no problems, but larger stones (>2.5cm) can become impacted at narrow points within the intestine, most commonly the distal ileum.

The gallbladder is closely related to the duodenum, and most cases of gallstone ileus involve a cholecystoduodenal fistula. Less commonly, gallstones can erode into other organs such as the colon (cholecystocolonic fistula), stomach (cholecystogastric fistula), or jejunum (cholecystojejunal fistula). Extremely rarely, there is no fistula, and a large stone passes through a dilated common bile duct.

The process of fistulation through the gallbladder wall takes many years. Gallstone ileus is much more common in elderly patients, especially those in their 70s and 80s. The majority of patients will have no pre-existing diagnosis of gallstones.

Clinical features

Gallstone ileus typically presents with cardinal features of intestinal obstruction, which are colicky abdominal pain, distension, vomiting and absolute constipation. This may occur suddenly, but older patients often present with a vague or insidious onset of gastrointestinal symptoms, which may be mistakenly attributed to another pathology, such as a concurrent chest or urinary infection.

Some patients may report episodes of RUQ pain due to flare-ups of cholecystitis or longer-term symptoms of pain, indigestion, nausea, loss of appetite and weight loss due to the progression of the underlying fistula.

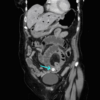

Investigations

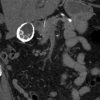

Patients should undergo standard initial investigations for suspected intestinal obstruction. In the past this would have included an abdominal X-ray, but this test is of limited value and is no longer used routinely. Patients with symptoms of bowel obstruction should proceed directly to a CT scan, which has a 99% diagnostic accuracy for gallstone ileus. It can also pinpoint the exact location of the stone(s), characterise the underlying fistula and identify any signs of bowel perforation or ischaemia.

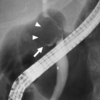

Rigler’s triad

Rigler’s triad describes the radiological features of gallstone ileus. It consists of small bowel obstruction, pneumobilia (gas in the biliary tree) and an ectopic gallstone.

Rigler’s triad is only seen on about 15% of abdominal X-rays, as most gallstones are non-calcified and not radiopaque. However, it is present on up to 80% of CT scans, as these can detect most non-calcified stones.

Management

Patients with gallstone ileus should receive the standard initial treatment for bowel obstruction, including nil by mouth, IV fluid resuscitation, and wide-bore nasogastric tube decompression.

Conservative management is not feasible, as only 1% of stones will pass on their own. Gallstone ileus requires emergency surgery unless the patient is considered too frail to meaningfully benefit from this.

The operation for gallstone ileus is called an enterolithotomy. This involves making a short midline (or “mini-laparotomy”) incision, opening the bowel and removing the impacted stone. Before stitching up the hole, the proximal bowel is carefully checked for any other stones, which are milked down and removed to prevent recurrent obstruction.

There is much debate about how to manage the underlying fistula. Some surgeons advocate immediate cholecystectomy and repair of the fistula to prevent further complications, but this has been shown to considerably worsen patient outcomes. Others recommend a staged approach with delayed cholecystectomy and fistula repair once the patient has recovered, although this is also fairly risky.

In reality, more than 80% of patients who survive their emergency operation are left well alone afterwards. Around 5% of these will develop recurrent bowel obstruction, and around 10% will experience infective complications such as cholecystitis or cholangitis.

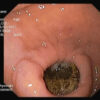

Bouveret’s syndrome

Bouveret’s syndrome is a vanishingly rare type of gallstone ileus. It has a similarly high mortality of up to 30%. The process of gallbladder wall erosion and cholecystoduodenal fistula formation is the same, but instead of following the normal flow direction along the intestine, a large gallstone migrates upstream and gets stuck in the pylorus of the stomach or the proximal duodenum. This leads to gastric outlet obstruction with epigastric pain, nausea and profuse vomiting. These symptoms are often misdiagnosed as gastroenteritis or another concurrent infection.

Bouveret’s syndrome tends not to be particularly obvious on plain X-rays. There may be a dilated stomach or an ectopic calcified gallstone in the upper abdomen. A CT scan will accurately confirm the diagnosis in most cases.

The first-line treatment for Bouveret’s syndrome is to attempt endoscopic stone extraction via an OGD. This is ideal for frail older patients as it is minimally invasive and does not require a general anaesthetic. Unfortunately, endoscopic treatment fails in more than half of cases. If this occurs, the patient will need a surgical enterolithotomy via an upper midline laparotomy, followed by careful consideration of the need for a cholecystectomy and/or delayed fistula repair.

Gallbladder mucocele

A mucocele is the distension of a hollow organ or cavity with mucinous fluid. A gallbladder mucocele (also known as gallbladder hydrops) is a relatively uncommon chronic complication of gallstones which occurs when a stone gets stuck in the gallbladder neck or cystic duct for a long time without causing inflammation or infection.

The protracted blockage prevents bile from entering the gallbladder and stops normal secretions from getting out. This causes the gallbladder to gradually distend as it fills with clear mucus or watery fluid. Mucocoeles can be very large and may contain up to 1500ml of secretions.

Most gallbladder mucoceles are asymptomatic and are diagnosed when the patient is incidentally found to have a palpable RUQ mass on abdominal examination. Some patients with a history of longstanding symptomatic gallstones or recurrent biliary colic are found to have a “surprise” mucocele during elective surgery.

The stagnant fluid within a mucocele is at risk of becoming infected, and some patients will therefore present as an emergency with acute cholecystitis or gallbladder empyema. Rarely, the high pressure within the mucocele may cause it to perforate, resulting in widespread peritonitis.

Surgery is recommended due to the risk of infective complications. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be technically challenging in these cases as the impacted stone gets in the way of the dissection planes. There is also a high chance of conversion to open surgery if the gallbladder is significantly enlarged.

Chronic cholecystitis

Chronic cholecystitis is a very common complication of gallstones. It is caused by stones repeatedly getting stuck in the gallbladder neck or cystic duct resulting in intermittent obstruction of bile flow, which provokes an ongoing inflammatory response.

The chronic inflammatory process damages the gallbladder wall, resulting in impaired smooth muscle contraction, poor emptying and bile stasis, exacerbating the situation further.

Patients typically present with subacute or intermittent symptoms similar to acute cholecystitis but less severe. Most people will also report malabsorptive features of longstanding symptomatic gallstones, such as indigestion, bloating, flatulence and intolerance of fatty foods.

An ultrasound scan will show gallstones and a fibrotic-looking gallbladder with variable degrees of wall thickening but no other features of acute inflammation. At the time of surgery, the gallbladder is often found to be small, scarred and shrunken (looking more like an angry walnut than a pear) and can be more difficult than usual to remove.

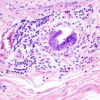

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis is a rare variant of chronic cholecystitis characterised by a destructive local inflammatory process with proliferative fibrosis. This results in marked gallbladder wall thickening, which may spread to involve adjacent organs, making it hard to differentiate from cancer on a scan.

Porcelain gallbladder

A porcelain gallbladder (also known as a calcified gallbladder or calcified cholecystitis) is a rare chronic complication of gallstones. It is characterised by extensive calcification of the gallbladder wall secondary to chronic cholecystitis, which may obliterate the mucosal lining and completely replace the muscle layer.

Patients with a porcelain gallbladder are usually asymptomatic. It is often an incidental finding on X-rays or CT scans and can be diagnosed by its characteristic appearance. Intraoperatively the gallbladder wall has a blue discolouration and can be brittle and fragile, often breaking or tearing when handled.

A porcelain gallbladder was historically associated with a very high risk of gallbladder cancer and was considered an absolute indication for cholecystectomy. However, more recent evidence has shown a much lower incidence of cancer than was previously thought. The current literature advocates patient-centred decision-making, taking into account specific radiological features along with their age, symptoms and overall fitness for surgery.

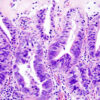

Gallbladder cancer

Gallbladder cancer is a rare but dreaded complication of gallstones, as it is often diagnosed at an advanced stage when it is no longer curable. It is the most common biliary cancer and the sixth most common gastrointestinal cancer. It currently accounts for around 1.7% of all cancer deaths worldwide.

Gallbladder cancer is almost always an adenocarcinoma. It develops due to accumulated oncogenic mutations induced by a prolonged inflammatory process such as chronic cholecystitis.

It is five times more likely in people with gallstones and is more likely to affect those with cholesterol stones, stones larger than 3cm and longstanding gallstones present for more than 20 years.

Other risk factors include native Indigenous populations, South Asian ethnicity, primary sclerosing cholangitis, smoking, obesity and chronic infections such as typhoid.

Clinical features

Patients may have longstanding symptoms of gallstones but are usually otherwise asymptomatic until the late stages of the disease. Advanced gallbladder cancer presents with the insidious onset of atypical or constant RUQ pain and a RUQ mass, along with other red-flag symptoms such as loss of appetite, weight loss, fatigue or jaundice.

Investigations

An ultrasound scan will show suspicious wall thickening or a gallbladder mass. This should be followed up with formal staging using CT, MRI and PET scans and referral to a specialist HPB cancer MDT.

Management

Gallbladder cancer progresses rapidly via direct local invasion into the liver bed and adjacent organs, transcoelomic spread across the peritoneal cavity, and lymphatic and haematogenous metastasis.

Only 10-20% of tumours are resectable at the time of diagnosis, and most require a radical cholecystectomy with liver resection and portal lymphadenectomy. The overall prognosis is very poor, with a mean survival of less than 12 months and 10-15% 5-year survival.

Fortunately, many gallbladder cancers are found incidentally in gallbladders sent off to the lab after removal. It is estimated that 0.5-1% of cholecystectomy specimens contain a small tumour. These cancers are generally diagnosed at a very early or premalignant stage and have an excellent 5-year survival of more than 95%.

Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma is another rare but devastating complication of gallstones. It is less common than gallbladder cancer but is even more difficult to treat. It currently causes around 2% of cancer deaths globally, and its incidence is increasing.

Cholangiocarcinoma is an adenocarcinoma which originates from the epithelial lining of the bile ducts. It is divided into intrahepatic and extrahepatic subtypes depending on where it arises within the biliary tree. Extrahepatic tumours involving the hepatic duct bifurcation are the most common, accounting for more than half of cases. These are also known as hilar cholangiocarcinomas or Klatskin tumours.

Gallstones are strongly associated with all types of cholangiocarcinoma. The odds of developing an extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma are three times higher in people with gallbladder stones, and eighteen times higher in people with bile duct stones. Having a cholecystectomy appears to remove this risk completely after about 10 years.

Other risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma include East Asian or Thai ethnicity, choledochal cysts, Caroli disease, primary sclerosing cholangitis, chronic pancreatitis, cirrhosis, viral hepatitis, and liver flukes.

Clinical features

Like gallbladder cancer, cholangiocarcinoma progresses rapidly and is usually asymptomatic until it is too late. Patients often have longstanding background symptoms related to gallstones or CBD stones, suddenly developing jaundice when the tumour obstructs the bile duct. The jaundice is classically painless but may be associated with upper abdominal or back pain. Systemic symptoms such as anorexia, weight loss and fatigue are common.

Investigations

Ultrasound and CT scans will show biliary dilatation but are unlikely to spot small tumours. An MRI of the liver is the best non-invasive test as it visualises the tumour, bile ducts and blood vessels in detail. EUS and ERCP can be used to further assess resectability and obtain samples for cytology.

Management

Only around 25% of tumours are potentially resectable at diagnosis. Surgery involves a complex liver and bile duct resection (for intrahepatic and hilar tumours) or a Whipple’s procedure with resection of the bile duct, pancreatic head and duodenum (for distal extrahepatic tumours). The risks of post-operative mortality, morbidity and recurrence are considerable. Cholangiocarcinoma has a dismal prognosis, with a median survival of less than 12 months and 5-year survival of less than 10%.

Cholecystoenteric fistula

This phenomenon has already been mentioned as the cause of gallstone ileus. It is a rare complication of gallstones in which a chronically inflamed gallbladder erodes into part of the GI tract, forming a fistula between two organs. It most commonly involves the duodenum but may also involve the colon or stomach. It is sometimes identified on preoperative imaging – gas in the gallbladder is a worrying sign – but usually gives the surgeon an unexpected fright during a cholecystectomy.

Cholecystoenteric fistulas are very challenging to manage, as the scar tissue around the gallbladder can be extremely difficult to dissect, and the hole in the bowel must be meticulously repaired.

Differential diagnoses (things that aren’t gallstones)

Gallbladder polyps

Gallbladder polyps are a group of benign lesions which project from the mucosal lining of the gallbladder into the lumen. They affect around 5% of people and are more common in men. They are usually asymptomatic and picked up as incidental findings on ultrasound but sometimes cause symptoms similar to biliary colic.

Larger polyps are more likely to be adenomas, which carry a risk of malignant transformation into gallbladder cancer. Current guidelines recommend cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallbladder polyps >1cm in size. Smaller asymptomatic polyps should be monitored with regular ultrasound scans and removed if they appear to grow.

Acalculous cholecystitis

Acalculous cholecystitis is acute inflammation of the gallbladder without evidence of gallstones.

It represents 5-10% of cases of acute cholecystitis and has a mortality of 30-50%. Acalculous cholecystitis usually affects critically unwell patients with a severe systemic illness such as trauma, sepsis or heart failure. It is more likely to affect people who are diabetic, immunocompromised or on total parenteral nutrition.

Acalculous cholecystitis has been described as an “ileus of the gallbladder”. It is thought to be caused by bile stasis resulting from dehydration, reduced oral intake and gallbladder wall ischaemia. This leads to inflammation, infection of stagnant bile and a high risk of gallbladder necrosis and perforation. Making the diagnosis is often challenging because the patient tends to be unconscious in the ICU. Most of these patients are too unwell to undergo surgery and are ideally managed non-operatively with intravenous antibiotics and a percutaneous cholecystostomy.

Gallbladder volvulus

A gallbladder volvulus (also known as gallbladder torsion) is exceptionally rare. It occurs when the gallbladder suddenly twists on its mesentery, compressing the cystic duct and cystic artery. This rapidly leads to acute ischaemia and gangrene. It requires surgery as soon as possible.

Gallbladder dysfunction

Gallbladder dysfunction (also known as gallbladder dyskinesia or dysmotility) is a functional disorder characterised by biliary pain due to impaired gallbladder motility without any evidence of gallstones.

It causes symptoms identical to biliary colic, but the patient will have normal blood results and a normal ultrasound scan. After multiple presentations like this, they usually progress to having a full work-up with an MRCP, an EUS and an OGD, which definitively rule out CBD stones, sludge, microlithiasis and any gastric or duodenal pathology.

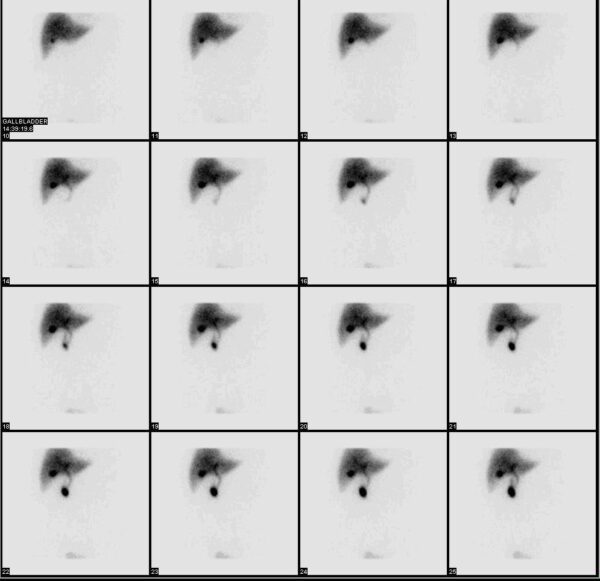

Eventually, a cholescintigraphy (or HIDA) scan will be performed to assess gallbladder emptying. A gallbladder ejection fraction of less than 35% over 60 minutes is considered diagnostic of gallbladder dysfunction. After months or years of being told there was nothing wrong with them, the long-suffering patient can finally be offered a cholecystectomy. However, they should be aware that not all patients with gallbladder dysfunction will experience long-term symptomatic relief after surgery.

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD or biliary dyskinesia) is another functional biliary disorder. It is characterised by attacks of severe RUQ and epigastric pain due to pathological spasms of the sphincter of Oddi without any evidence of gallstones. This produces transient biliary obstruction, which may result in deranged LFTs, biliary dilatation, and occasionally acute pancreatitis.

SOD typically affects young women (who tend to have very narrow bile ducts) and is especially common in people who have had a cholecystectomy. It can be worsened by opiates, which trigger contraction of the sphincter muscle. Patients often request atypical analgesic regimens which avoid morphine in favour of drugs such as tramadol or pethidine which do not affect sphincter function.

SOD is diagnosed by using endoscopic manometry to directly measure the sphincter pressures. An elevated basal sphincter pressure of ≥40mmHg is considered diagnostic. If the diagnosis is confirmed, the endoscopist can inject botulinum toxin to temporarily relax the sphincter or perform a definitive sphincterotomy by cutting the muscle open. Many patients suffer persistent chronic pain.

Post-cholecystectomy syndrome

Post-cholecystectomy syndrome describes the persistence or recurrence of biliary pain following a cholecystectomy.

Unfortunately, this affects up to 40% of patients. It is poorly understood and may be due to altered bile flow or post-operative complications such as strictures, subacute bile leaks, retained or spilt stones, long cystic duct stumps, fluid collections or bile acid malabsorption. In some cases, it may be that the patient’s symptoms were not actually due to gallstones and were caused by something else (e.g. IBS, an ulcer, or a pancreatic tumour).

Abdominal pain has hundreds of potential causes, so it’s important to always keep an open mind. And if you’re seeing a patient with RUQ pain, always check whether they still have a gallbladder!

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

Reference texts

- The SAGES Safe Cholecystectomy Program. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2019. Clinical Knowledge Summary: Gallstones. Available from [LINK]

- Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver. 2012 Apr;6(2):172-87.

- Bass G, Gilani SN, Walsh TN. Validating the 5Fs mnemonic for cholelithiasis: time to include family history. Postgrad Med J. 2013 Nov;89(1057):638-41.

- Vítek L, Carey MC. New pathophysiological concepts underlying pathogenesis of pigment gallstones. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012 Apr;36(2):122-9.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2014. CG188 Gallstone disease: diagnosis and management. Available from: [LINK]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of gallstones. J Hepatol 2016;65:146-181.

- Pisano M, Allievi N, Gurusamy K, et al. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2020 Nov 5;15(1):61.

- Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):41-54.

- Gurusamy KS, Davidson C, Gluud C, Davidson BR. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for people with acute cholecystitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 30;(6):CD005440.

- Williams E, Beckingham I, El Sayed G, et al. Updated guideline on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2017 May;66(5):765-782.

- Kiriyama S, Kozaka K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):17-30.

- Miura F, Okamoto K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: initial management of acute biliary infection and flowchart for acute cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):31-40.

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10.

- Du L, Cen M, Zheng X, et al. Timing of Performing Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography and Inpatient Mortality in Acute Cholangitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar;11(3):e00158.

- Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis–2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013 Jan;62(1):102-11.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2018. NICE Guidance NG104: Pancreatitis. Available from [LINK]

- Leppäniemi A, Tolonen M, Tarasconi A, et al. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2019 Jun 13;14:27.

- Csendes A, Díaz JC, Burdiles P, et al. Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystobiliary fistula: a unifying classification. Br J Surg. 1989 Nov;76(11):1139-43.

- Beltrán MA. Mirizzi syndrome: history, current knowledge and proposal of a simplified classification. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Sep 14;18(34):4639-50.

- Inukai K. Gallstone ileus: a review. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019 Nov 24;6(1):e000344.

- Lassandro F, Gagliardi N, Scuderi M, et al. Gallstone ileus analysis of radiological findings in 27 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2004 Apr;50(1):23-9.

- Ravikumar R, Williams JG. The operative management of gallstone ileus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010 May;92(4):279-81.

- Caldwell KM, Lee SJ, Leggett PL, et al. Bouveret syndrome: current management strategies. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018 Feb 15;11:69-75.

- Towfigh S, McFadden DW, Cortina GR, et al. Porcelain gallbladder is not associated with gallbladder carcinoma. Am Surg. 2001 Jan;67(1):7-10

- Stephen AE, Berger DL. Carcinoma in the porcelain gallbladder: a relationship revisited. Surgery. 2001 Jun;129(6):699-703.

- Machado NO. Porcelain Gallbladder: Decoding the malignant truth. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016 Nov;16(4):e416-e421.

- Rawla P, Sunkara T, Thandra KC, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of gallbladder cancer. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019 May;5(2):93-102.

- Hundal R, Shaffer EA. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014 Mar 7;6:99-109.

- Kanthan R, Senger J, Ahmed S, Kanthan SC. Gallbladder cancer in the 21st Journal of Oncology, 2015, Article ID 967472.

- Banales JM, Marin JJG, Lamarca A et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 17, 557–588 (2020).

- Nordenstedt H, Mattsson F, El-Serag H, Lagergren J. Gallstones and cholecystectomy in relation to risk of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2012 Feb 28;106(5):1011-5.

- Aloia TA, Járufe N, Javle M, et al. Gallbladder cancer: expert consensus statement. HPB (Oxford). 2015 Aug;17(8):681-90.

- Farkas J. The Internet Book of Critical Care: Acalculous Cholecystitis. EMCRIT 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Gurusamy KS, Junnarkar S, Farouk M, Davidson BR. Cholecystectomy for suspected gallbladder dyskinesia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD007086.

- Bistritz L, Bain VG. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: managing the patient with chronic biliary pain. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Jun 28;12(24):3793-802.

Image references

- Figure 1. OpenStax College. 2425 Gallbladder. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 2. Hic et nunc. Gallenblase. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 3. Mischinger et al. Fig 1 – Hepatocystic triangle and triangle of Calot. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 4. Sebastian et al. Fig 1 – Photographic documentation of the critical view of safety. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 5. Adapted from BruceBlaus. Gallbladder (organ). Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 6. Bakerstmd. Cholangiogram with labels. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 7. Jakupica. Жолчни камења, Gallstones. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 8. Stell98. Gallensteine 2006 03 28. Licence: [public domain]

- Figure 9. Miya.m. Gallstone black01. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 10. Mikael Häggström MD. Ultrasonography of sludge and gallstones, annotated. Licence: [public domain]

- Figure 11. Nevit Dilmen. Ultrasound image of gallbladder stone Gallstone 091937515. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 12. Nevit Dilmen. Gallstone 0407115810734. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 13. Mikael Häggström MD. Ultrasonography of cholecystitis. Licence: [public domain]

- Figure 14. James Heilman MD. GBthick,GS,large. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 15. Hellerhoff. Gedeckt perforierte Cholezystitis 71W – CT axial und coronar KM pv – 001. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 16. James Heilman MD. Jaundice08. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 17. Sheila J Toro. Scleral Icterus. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

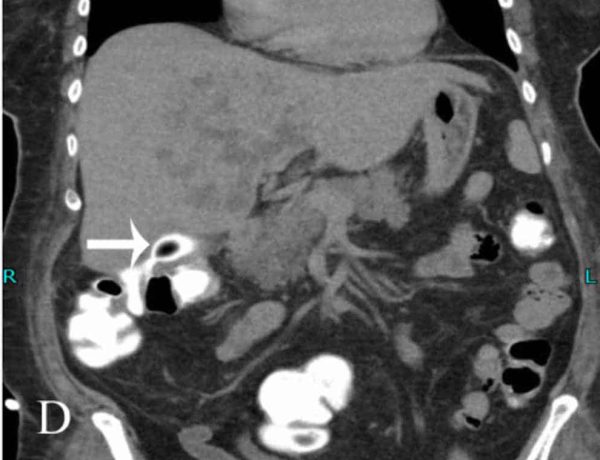

- Figure 18. J Peña, JETem. Choledocholithiasis. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

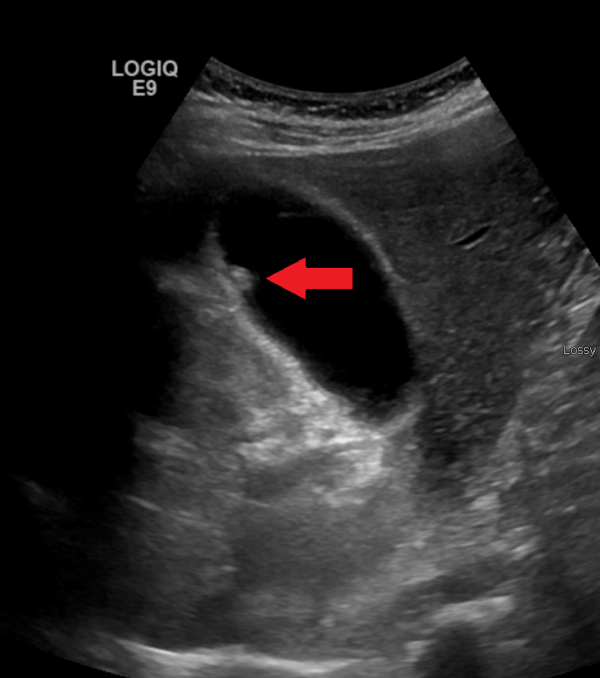

- Figure 19. Samir. CBD stones. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 20. J Guntau. ERCP Roentgen. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 21. Samir (The Scope). Pigment stone extraction. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 22. J Guntau. Perkutan transhepatische Cholangiographie. Licence: [public domain]

- Figure 23. Adapted from ChocChocsugarsugar. Normal Pancreas VS Pancreatic Agenesis. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 24. Hellerhoff. Pankreatitis exsudativ CT axial. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 25. Hellerhoff. Akute exsudative Pankreatitis – CT axial. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 26. Sugo et al. Figure 2. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 27. Sugo et al. Figure 3. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 28. L Penninga. Figure 1. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 29. K Drinnon and Y Puckett. Figure 1: Gallstone ileus. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 30. Hellerhoff. Bouveret-Syndrom case 001 – CT – coronar – 006. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 31. Nabais et al. Figure 3. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 32. Nabais et al. Figure 4. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 33. Mikael Häggström MD. Enlarged gallbladder with gallstone and cholecystitis. Licence: [public domain]

- Figure 34. Herbert L Fred and Henrik A van Dijk. Porzellangallenblase. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 35. Adapted from Hellerhoff. Porzellangallenblase mit zusaetzlichen Konkrementen 85W – CT KM arteriell – 001. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 36. KGH. Gallbladder adenocarcinoma (2) histopathology. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 37. KGH. Gallbladder adenocarcinoma (3) lymphatic invasion histopathology. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 38. James Heilman MD. Obstructivebiliarydilatation. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 39. Abbasi et al. Figure 2D. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 40. James Heilman MD. GBPolypMark. Licence: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 41. Myohan. HIDA. Licence: [CC BY-SA]