- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Paracetamol (also called acetaminophen in some countries) is the most commonly used non-prescription analgesia globally and one of the most used in intentional overdoses.1 In 2021, almost 5000 deaths were related to drug poisoning in England and Wales, and over 200 were due to paracetamol poisoning.2

This article will cover the assessment and management of paracetamol overdose in adults. Managing paracetamol overdose can be complex. Advice from TOXBASE (in the UK) and local guidelines should be followed when assessing and managing these patients.

Aetiology

Pharmacology of paracetamol

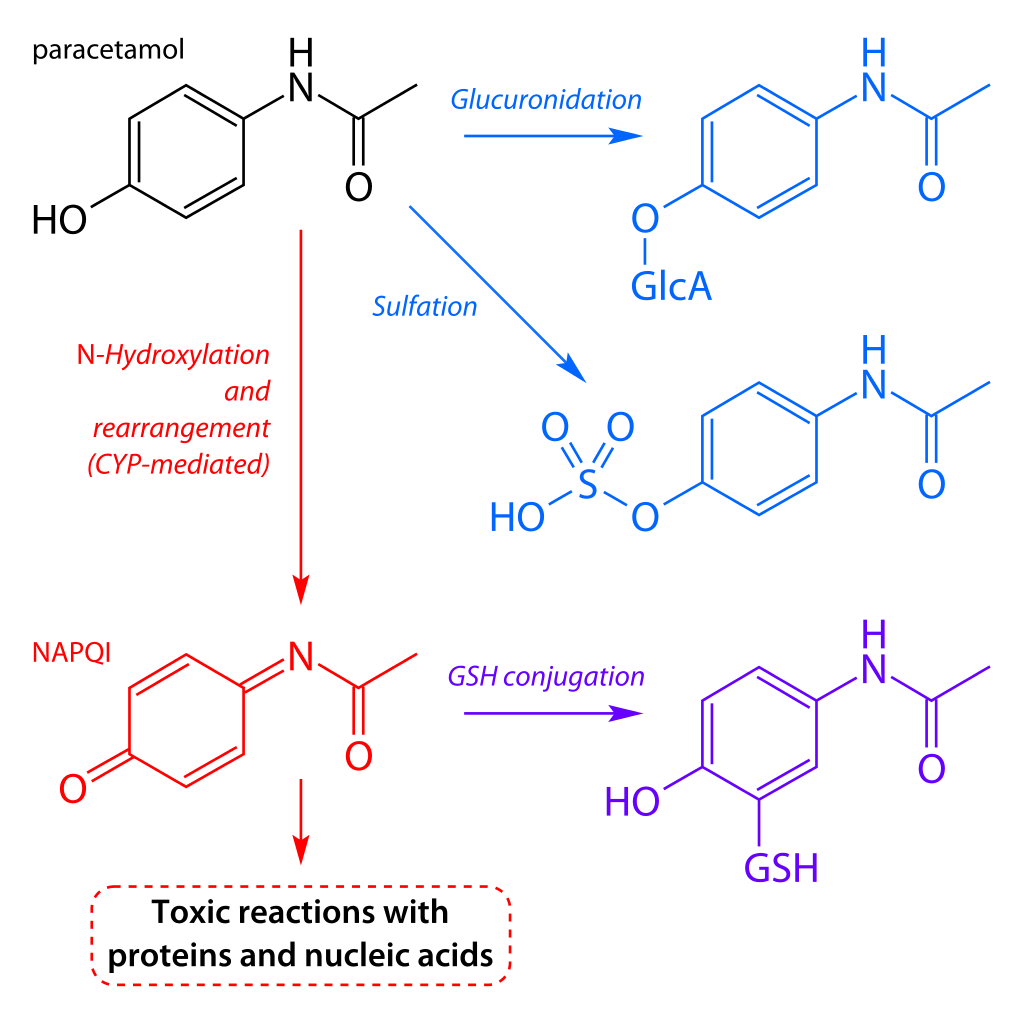

The therapeutic dose of paracetamol in adults is 1g four times a day with a maximum of 4g per day. After consumption, approximately 95% of paracetamol undergoes glucuronidation (a form of metabolism) to create a water-soluble paracetamol conjugate that is eliminated in the urine.

The remaining 5% is metabolised using cytochrome P450 enzymes to a toxic metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). Routinely, NAPQI binds to glutathione (another protein in the body) to become a mercapturate derivative, a non-toxic metabolite that gets excreted in the urine.

Outside therapeutic doses, the production of NAPQI can significantly exceed the body’s detoxification capacity due to the finite amount of glutathione available.

Excess NAPQI binds to the hepatocytes causing mitochondrial injury and, in severe cases, may cause acute liver failure or even death.

Overdose

The causes of paracetamol toxicity are variable, some intentional (due to self-harm) or unintentional (due to therapeutic excess error).

The National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) defines three different types of paracetamol overdose:4

- Acute overdose: excess amounts of paracetamol ingested over less than one hour, usually in the context of self-harm

- Staggered overdose: excess amounts of paracetamol ingested over longer than one hour, usually in the context of self-harm

- Therapeutic excess: excess paracetamol ingested with the intent to treat pain or fever and without the intent of self-harm

Therapeutic excess involves paracetamol being ingested above the licensed daily dose and more than or equal to 75mg/kg in 24 hours. It can involve excessive doses of the same paracetamol product or the inadvertent use of multiple paracetamol-containing products simultaneously.

In rare cases, paracetamol toxicity can result from normal use, possibly due to the idiosyncratic differences between individuals’ enzyme activities during the metabolism process.5

Risk factors

As mentioned, paracetamol overdose can occur intentionally or unintentionally. However, some risk factors can exacerbate the severity of the toxicity.1

Table 1. Risk factors for increased severity of toxicity.

| Risk factor | Rationale |

| History of self-harm | Paracetamol is one of the most widely used analgesics and is accessible |

| History of frequent or repeated use of medication for pain relief | Paracetamol can be in many products, and patients may not realise they have overdosed when taking multiple different brands of medications |

| Low body weight (<50kg) | Unintentional overdose in patients has occurred due to a low body weight not being accounted for when prescribing |

| Cytochrome P450 inducers | CYP450 inducers such as phenytoin, phenobarbital, rifampicin, or primidone may increase the risk of liver injury following a paracetamol overdose |

| Glutathione deficiency |

|

Clinical features

Clinical features are highly variable and dependent on the ingestion method (acute, staggered or acute on chronic overdose) and the time from overdose to presentation.

Paracetamol is often combined with opioids (e.g. codeine and dihydrocodeine); thus, a concomitant opioid toxidrome may be present.

Typical early clinical features (<12 hours) include:1

- Potentially asymptomatic

- Nausea and vomiting

- Mild/moderate abdominal pain/tenderness

Typical late clinical features (12 – 36 hours) include:1

- Moderate/severe abdominal pain

- Metabolic acidosis

- Jaundice

- Acute kidney injury

- Hepatic encephalopathy

- Coma

- Bruising or systemic haemorrhage may indicate coagulopathy secondary to impaired hepatic clotting factor production

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Preparation ingested: combination, strength

- Length of time the paracetamol products were ingested over

- Time since ingestion

Investigations

Laboratory investigations

Not all patients will require investigation following a paracetamol overdose (see management section).

However, if indicated, relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Paracetamol concentration*

- Liver function tests

- INR

- Urea and electrolytes

- Plasma bicarbonate

- Plasma glucose

- Full blood count

* Some laboratory analysers may underestimate paracetamol concentration by as much as 40% if the blood test is taken during treatment with acetylcysteine. Always check and follow local laboratory guidelines.

Management

When to refer

The following patients require hospital assessment following paracetamol overdose:

- The presence of symptoms (e.g. jaundice)

- Deliberate paracetamol overdose for self-harm (regardless of dose)

- Ingested dose >75 mg/kg over 1 hour or less

- All staggered paracetamol overdoses

When to treat

Management of paracetamol overdose depends on the type of overdose (acute vs staggered), time since ingestion and patient characteristics.

An accurate history ensures the patient is investigated and managed appropriately. Some patients may not require blood tests, whereas some require immediate treatment pending blood test results.

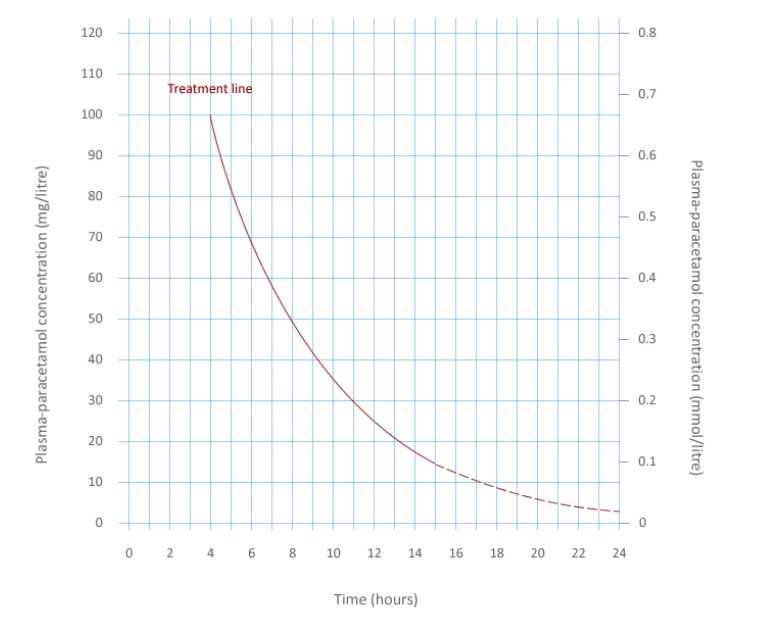

Paracetamol overdose management is dependent on the severity and category of the overdose. Provided the time interval since ingestion is greater than four hours, a paracetamol treatment graph can be used to rationalise treatment (Figure 2).6

Table 2. The categories of paracetamol overdose require different approaches to assessment, investigations and management:1

| Overdose category | Assessment & management |

| Acute overdose (ingested over one hour or less) | |

| Presenting <8 hours of ingestion |

|

| Presenting 8-24 hours after last ingestion |

|

| Presenting more than 24 hours after last ingestion |

|

| Staggered paracetamol overdose (ingested over >1 hour) | |

| All patients |

|

| Therapeutic excess | |

| All patients |

|

Treatment of paracetamol overdose

NICE and NPIS recommend intravenous acetylcysteine to prevent/lessen liver damage secondary to a paracetamol overdose, with its effectiveness greatest within eight hours of paracetamol ingestion.

There are currently two acetylcysteine regimens used in the UK:7

- Standard 21-hour regimen: 150mg/kg over one hour, then 50mg/kg over four hours, then 100mg/kg over 16 hours

- Modified 12-hour Scottish & Newcastle Acetylcysteine Protocol (SNAP) regimen: 100mg/kg over two hours, then 200mg/kg over 10 hours

To avoid excessive dosage in obese patients, a ceiling weight of 110 kg should be used when calculating the dose for paracetamol overdosage.

Paracetamol overdose during pregnancy

NPIS advises that for pregnant patients, the toxic dose should be calculated using the patient’s pre-pregnancy weight, and the acetylcysteine dose should be calculated using the patient’s actual pregnant weight.

Stopping treatment

Patients should have repeat blood tests (including paracetamol concentration, INR, and LFTs) taken before the end of treatment with acetylcysteine. Decisions around stopping treatment are complex and depend on the clinical situation. Advice from TOXBASE (in the UK) and local clinical guidelines should be followed.

Allergies and adverse effects

A previous anaphylactic reaction to acetylcysteine is not a contraindication for further treatment. Prophylactic treatment with antihistamines should be considered in patients with a history of previous sensitivities to acetylcysteine.

If paracetamol concentrations are low or absent, acetylcysteine is more likely to cause adverse effects. Adverse effects are more prevalent in women, asthmatics, and patients with a family history of allergy.

Intentional paracetamol overdose

Once medically fit for discharge, all patients who have taken a deliberate overdose should undergo a psychosocial assessment of their needs and risks by a specialist mental health professional. The person’s subsequent management is based on this assessment.

Complications

Following excessive ingestion of paracetamol, it is common for patients to develop nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain.

Significant complications due to paracetamol overdose include:

- Acute liver failure

- Renal impairment

- Death

Significant complications are rare due to the availability of acetylcysteine (a highly effective antidote).

King’s College Criteria

Patients with signs of severe acute liver injury may require discussion with specialist liver units.

The King’s College Criteria (KCC) can be used to identify which patients with fulminant hepatic failure who should be referred for liver transplantation. The KCC indicators predict a poor prognosis and identify patients most likely to benefit from a liver transplant referral.

KCC is specific but not sensitive, so all these patients should be discussed with gastroenterology or liver specialists.

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- BMJ Best Practice. Paracetamol overdose in adults. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Office for National Statistics. Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales: 2021 registrations. Published in 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Fvasconcellos. Paracetamol metabolism. License: [Public domain]

- National Poisons Information Service / TOXBASE. Paracetamol. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Vuppalanchi, R., Liangpunsakul, S., & Chalasani, N. (2007). Etiology of new-onset jaundice: how often is it caused by idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury in the United States?. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology ACG, 102(3), 558-562.

- Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Paracetamol overdose: Simplification of the use of intravenous acetylcysteine. License: [OGL]

- Pettie, J. M., Caparrotta, T. M., Hunter, R. W., Morrison, E. E., Wood, D. M., Dargan, P. I., … & Dear, J. W. (2019). Safety and efficacy of the SNAP 12-hour acetylcysteine regimen for the treatment of paracetamol overdose. EClinicalMedicine, 11, 11-17.