- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases which cause progressive optic neuropathy commonly associated with raised intraocular pressure (IOP).

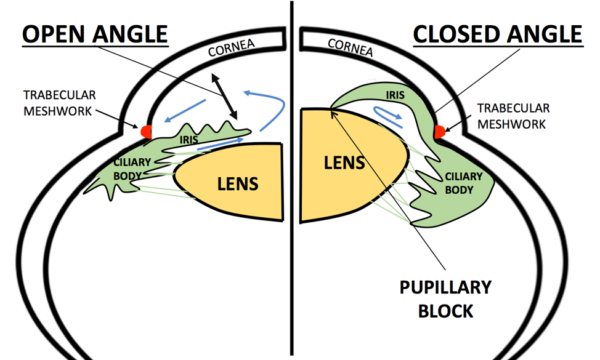

Glaucoma can be open angle or closed angle depending on the anatomical structure of the anterior chamber of the eye.

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common type associated with an open anterior chamber angle of the eye. POAG affects 2% of people in the UK over 40 years old and is mainly seen in older people.1

There are a few different types of glaucoma to be aware of, particularly acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG) which is an ophthalmic emergency. However, AACG is rare, and this article will concentrate on POAG.

Aetiology

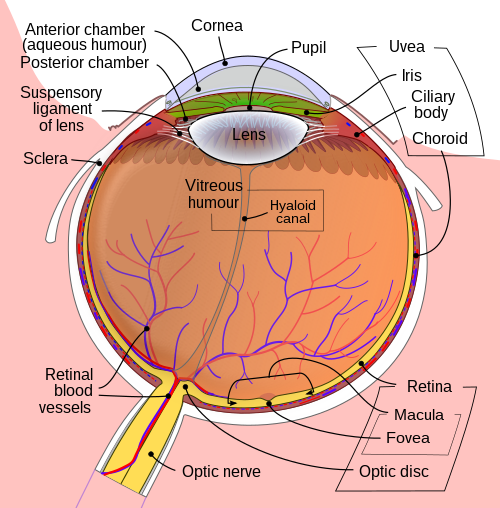

Anatomy

Aqueous humour is a clear fluid which supplies nutrients to the cornea and lens. It is produced by the ciliary body and travels from the posterior chamber through the pupil into the anterior chamber.

The aqueous humour then drains out of the anterior chamber through two independent pathways:

- The trabecular meshwork into the canal of Schlemm in the iridocorneal angle

- The uveoscleral pathway

The constant cycle of production and drainage of aqueous humour helps maintain the eye in a normal pressured state of 12 – 21mmHg.

For more information on anatomy, see the Geeky Medics guide to eye anatomy.

Pathophysiology

In POAG, even though the iridocorneal angle appears open, there is increased resistance to the outflow of aqueous humour through the trabecular meshwork into the canal of Schlemm.

This causes the IOP to rise, which if sustained will lead to retinal ganglion cell death causing permanent visual loss.

In POAG the loss of retinal ganglion cells and the nerve fibre layer usually follows a pattern of inferior loss occurring before superior loss.

This pathophysiology differs from the acute rise in IOP seen when the angle becomes closed in acute angle-closure glaucoma.

Risk factors

Risk factors for POAG include:2

- Myopia (short-sightedness)

- Increased age particularly after 65 years

- Family history

- African-Caribbean ethnic origin

- Untreated ocular hypertension (raised IOP)

- Cardiovascular disease

- Type two diabetes (this is a secondary glaucoma)

Clinical features

POAG is typically insidious in onset, following a slow and chronic course. It is usually adult onset and affects both eyes.

History

Unfortunately, in most cases, patients will be asymptomatic and not aware of any visual disturbances.

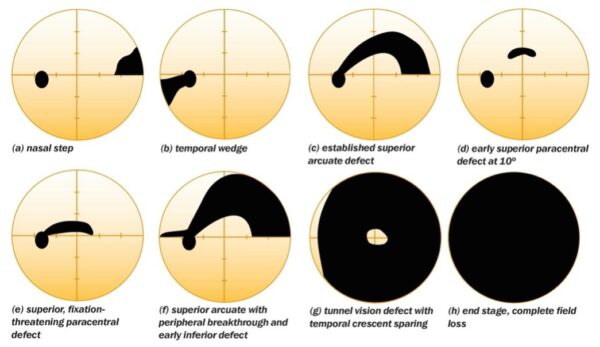

Initially, POAG causes loss of peripheral vision, usually in the superior visual field before the inferior visual field. As we don’t regularly use our superior visual field of vision, these early changes go unnoticed. Central vision loss occurs at the end stage of POAG.3,4

It is important to check if there is any relevant family history of glaucoma. People with a family history of glaucoma are entitled to free annual eye tests to screen for disease.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to ophthalmic history taking.

Clinical examination

POAG is usually picked up through routine eye checks by an optician.

The eye will not appear red or painful, as there is no acute rise in IOP or inflammation.

Typical clinical findings in POAG include:

- Increased IOP

- Visual field defects

- Fundoscopy: cupped optic discs

Investigations

Measuring intraocular pressure

The gold standard investigation to measure intraocular pressure is with a Goldmann applanation tonometer.

This device is mounted on a slit lamp and makes brief contact with the cornea after numbing with eye drops. It measures the pressure needed to indent the cornea by a specific surface area.

Non-contact tonometry may also be used to estimate intraocular pressure by opticians. This involves shooting a small puff of air at the cornea and measuring its rebound. Non-contact tonometry is less accurate but useful for general screening.

Optic nerve assessment

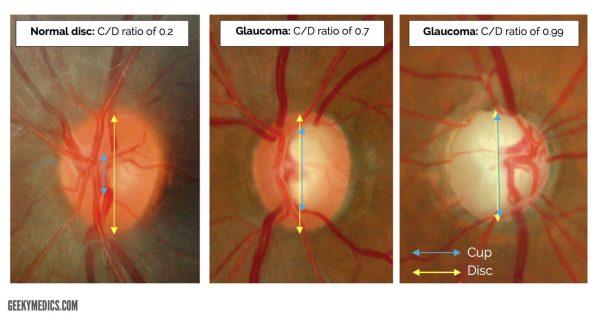

As glaucoma causes progressive optic neuropathy it is important to establish if there is any damage or changes to the optic nerve.

Fundoscopy with pupil dilatation can be performed using a handheld ophthalmoscope, or a stereoscopic slit lamp can be used for an improved view.

Optic disc examination is a direct marker of the disease progression. Damage is assessed by looking at the vertical optic cup-to-disc ratio, which will increase in glaucoma. A normal ratio is less than 0.5 though disc asymmetry is important too.

Glaucoma is suggested by an increased ‘cupped’ appearance of the optic disc over time.

Glaucoma can also lead to primary optic nerve atrophy. This describes the death of nerve fibres within the optic nerve and gives the appearance of a pale optic disc.

Visual field assessment

Visual field assessments will give evidence for loss of peripheral vision which a patient may not be consciously aware of.

Peripheral vision is particularly important in detecting movement outside the area of focus and is a key factor in determining eligibility for driving.

Other areas of the visual field lost will be dependent on the location of the damage at the optic nerve head.

Gonioscopy

Gonioscopy is the gold standard investigation for assessing the drainage angle of the anterior chamber between the iris and cornea.

In POAG this will show the angle is open. The trabecular meshwork will be visible.

Diagnosis

POAG will usually be picked up by an optometrist during routine eye checks.

If suspected, they will normally be referred to a consultant ophthalmologist for confirmation of the diagnosis.

NICE guidelines state to diagnose chronic open-angle glaucoma, the following tests should be offered:5

- Visual field assessment using standard automated perimetry

- Optic nerve assessment and fundus examination using stereoscopic slit lamp biomicroscopy, with pupil dilatation

- IOP measurement using Goldmann applanation tonometry (slit lamp mounted)

- Peripheral anterior chamber configuration and depth assessments using gonioscopy

- Central corneal thickness (CCT) measurement: IOP measurement can be affected by the corneal thickness, and allowances must be made

It is also important to obtain an image of the optic nerve head at diagnosis to keep as a baseline before initiating treatment.

Management

Treatment for suspected and confirmed POAG will be initiated under the guidance of an ophthalmologist.

The aim of treatment in POAG is to prevent the development and progression of optic nerve damage and preserve sight as much as possible. Different treatment options aim to reduce IOP to avoid further visual loss or impairment.

Treatment will usually be started in patients with an IOP >24mmHg.

Laser management

In 2022, NICE updated its guidance to recommend offering all newly diagnosed chronic open-angle glaucoma patients 360° selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT).

This involves using short pulses of low-energy light to target particular cells in the eye, triggering processes within the eye to remove and rebuild a meshwork that will function effectively and reduce the IOP.

Medical management

Medical management involves a variety of eye drop preparations that either reduce the production or increase the outflow of aqueous humour.6

First-line preparations include generic prostaglandin analogue (PGA) eye drops (e.g. latanoprost). Side effects of latanoprost may include eyelash growth, eyelid pigmentation and iris pigmentation.

Other pharmacological interventions include beta-blockers (e.g. timolol), carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g. acetazolamide) and parasympathomimetics (e.g. pilocarpine).

Surgical management

For patients with advanced open-angle glaucoma, surgery may be indicated.

Trabeculectomy surgery involves creating a channel in the sclera for aqueous humour to drain.

Glaucoma surgery is offered with pharmacological augmentation (using mitomycin-C). Mitomycin-C is an antimetabolite used during the initial stages of trabeculectomy to prevent excessive postoperative scarring and therefore reduce the risk of failure.

Tiny plastic shunts can also be inserted if needed, to create a permanent drainage channel for the aqueous humour.

Complications

The main complication of untreated glaucoma is the irreversible loss of vision. It is important to seek early advice and management to optimise vision as this can have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life.

Driving

Many patients when diagnosed with glaucoma worry about the possibility of losing their driving licence. However, if diagnosed and treated early, many people are still able to keep their licence.

In the United Kingdom, the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) requires patients to inform them of a new diagnosis of glaucoma if it affects both eyes (group 1/car drivers) or one eye (group 2/commercial drivers). This is a legal responsibility.7,8

Key points

- Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases which cause progressive optic neuropathy commonly associated with raised intraocular pressure (IOP).

- Primary open-angle glaucoma is associated with an open anterior chamber angle and is mostly seen in older people.

- In POAG there is increased resistance to the outflow of aqueous humour through the trabecular meshwork.

- Key risk factors include myopia, race, increased age and family history of glaucoma.

- Patients are typically asymptomatic and will not notice peripheral visual changes.

- The gold standard investigation to measure IOP is with a Goldmann tonometer.

- Treatment aims to prevent the development and progression of optic nerve damage. Management options include laser treatment, eye drop preparations and surgical interventions.

- The key long-term complication is the irreversible loss of vision which can have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life.

Reviewer

Dr Anne Gobbett

Speciality Doctor in Ophthalmology

Sunderland Eye Infirmary

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- NICE CKS. Glaucoma. March 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Sheybani, A. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. December 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- National Eye Institute. April 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Glaucoma UK. Primary Open Angle Glaucoma. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE. Glaucoma: Diagnosis and Management. January 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- NHS.uk Glaucoma. February 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Sachdev, A., Tahhan, M., Sung, V.C.T. Glaucoma and driving: Are we documenting driving status and advising patients with glaucoma appropriately about their driving? International Ophthalmology. 38, 419-423. February 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Glaucoma UK. Driving with glaucoma. Available from: [LINK]

- Mayo Clinic. October 2020. Available from: [LINK]

Image references

- Figure 1. Wikipedia. Rhcastilhos and Jmarchn. Schematic diagram of the human eye. Licence: [CC BY-SA 3.0]

- Figure 2. Moran CORE. Acute angle closure glaucoma. Licence [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0]

- Figure 3. Community Eye Health Journal. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [CC BY-NC 2.0]

- Figure 4. Community Eye Health Journal. License: [CC BY-NC 4.0]