- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

What is spirometry?

Spirometry is a method of assessing lung function by measuring the volume of air that the patient is able to expel from the lungs after a maximal inspiration. It is a reliable method of differentiating between obstructive airways disorders (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma) and restrictive diseases (e.g. fibrotic lung disease).

Aside from being used to classify lung conditions into obstructive or restrictive patterns, it can also help to monitor disease severity. This guide aims to provide a basic approach to spirometry interpretation.

Spirometry provides several important measures including:

- Forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1): the volume exhaled in the first second after deep inspiration and forced expiration, similar to PEFR.

- Forced vital capacity (FVC): the total volume of air that the patient can forcibly exhale in one breath.

- FEV1/FVC: the ratio of FEV1 to FVC expressed as a percentage.

Values of FEV1 and FVC are expressed as a percentage of the predicted normal for a person of the same sex, age and height.

Reference ranges

- FEV1: >80% predicted

- FVC: >80% predicted

- FEV1/FVC ratio: >0.7

Patient details

Confirm the patient’s details:

- Name

- Age

- Sex

- Height

- Ethnicity

Age, sex, height and ethnicity are used to calculate predicted normal values for the patient.

Assess the quality of results

Three consistent volume-time curves are required, of which the best two curves should be within 5% of each other.

The best of the three consistent readings of FEV1 and FVC should be used in your interpretation.

The expiratory volume-time graph should also be smooth and free from abnormalities caused by:

- Coughing during expiration

- Extra breath during expiration

- Slow start to forced expiration

- Sub-maximal effort

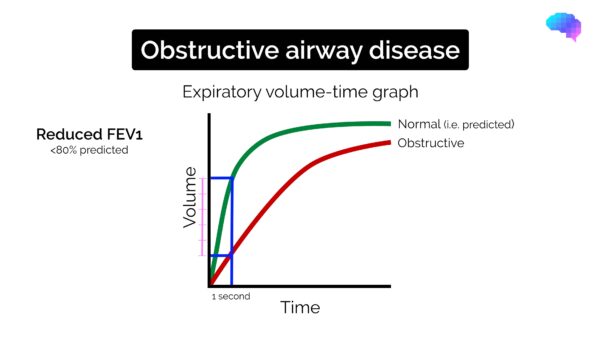

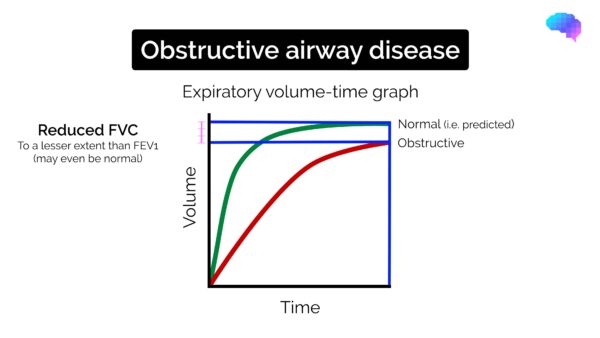

Obstructive spirometry pattern

Typical spirometry findings in obstructive lung disease include:

- Reduced FEV1 (<80% of the predicted normal)

- Reduced FVC (but to a lesser extent than FEV1)

- FEV1/FVC ratio reduced (<0.7)

Reversibility

It can be useful to assess reversibility with a bronchodilator if considering asthma as a cause of obstructive airway disease.

Patients should be asked to stop bronchodilator therapy prior to spirometry, to ensure previous treatments do not affect the results (if the patient has severe disease, this would not be advisable):

- Short-acting beta-2-agonists should be stopped 6 hours prior to testing.

- Long-acting beta-2-agonists should be stopped 12 hours prior to testing.

To assess reversibility, administer 400 micrograms of salbutamol and repeat spirometry after 15 minutes:

- The presence of reversibility is suggestive of a diagnosis of asthma.

- The absence of reversibility suggests fixed obstructive respiratory pathology such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Partial reversibility may suggest a coexisting diagnosis of asthma and another obstructive airway disease (e.g. COPD).

Aetiology of obstructive lung disease

Causes of obstructive lung disease include:

- COPD

- Asthma

- Emphysema

- Bronchiectasis

- Cystic fibrosis

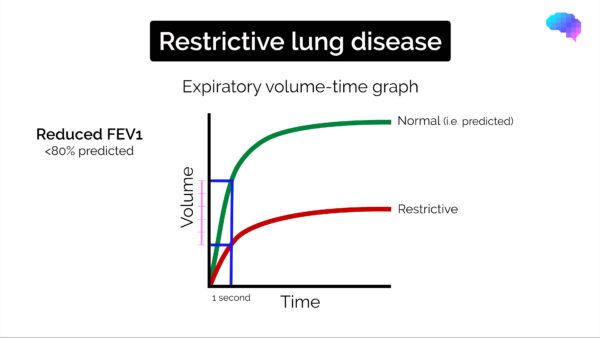

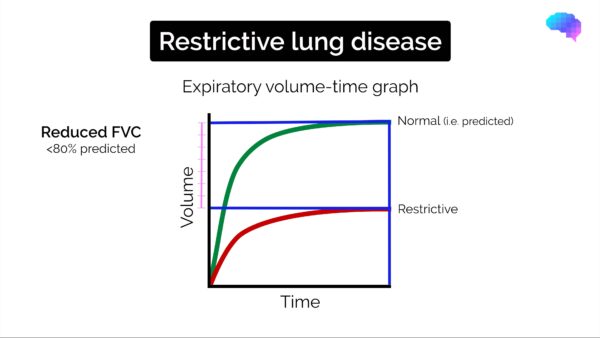

Restrictive spirometry pattern

Typical spirometry findings in restrictive lung disease include:

- Reduced FEV1 (<80% of the predicted normal)

- Reduced FVC (<80% of the predicted normal)

- FEV1/FVC ratio normal (>0.7)

Aetiology of restrictive lung disease

Causes of restrictive lung disease can be pulmonary or non-pulmonary in origin.

Pulmonary causes

Pulmonary causes of restrictive lung disease include:

- Pulmonary fibrosis

- Pneumoconiosis

- Pulmonary oedema

- Lobectomy/pneumonectomy

- Parenchymal lung tumours

Non-pulmonary causes

Non-pulmonary causes of restrictive lung disease include:

- Skeletal abnormalities (e.g. kyphoscoliosis)

- Neuromuscular diseases (e.g. motor neuron disease, myasthenia gravis, Guillan-Barre syndrome)

- Connective tissue diseases

- Obesity or pregnancy

References

- Spirometry in Practice: A Practical Guide to Using Spirometry in Primary Care 2nd Ed (2005). British Thoracic Society COPD Consortium. Available from: [LINK].

- Dr Colin Tidy. Spirometry. Patient.info. Published 2nd Dec 2016. Accessed on 12th Dec 2017. Available from: [LINK].