- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

The scaphoid is the most commonly fractured carpal bone, accounting for two-thirds of all carpal fractures.1

Typically, scaphoid fractures occur due to a fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH). Patients with snuffbox (scaphoid tubercle) tenderness and/or radial wrist pain should initially be treated as having a scaphoid fracture due to the risk of non-union in untreated or incorrectly managed scaphoid fractures.2

Aetiology

Pathophysiology

The most common mechanism of injury is a fall on an ulnar-deviated, pronated, and hyper-dorsiflexed (outstretched) wrist.2

Other mechanisms include axial loading to the wrist in neutral extension-flexion or a direct blow to the scaphoid.2

Anatomy

The scaphoid can be divided into four parts:

- Tubercle

- Distal pole

- Waist

- Proximal pole

The majority of scaphoid fractures involve the waist of the bone.3

The blood supply to the scaphoid includes:

- Dorsal carpal branch (branch of radial artery): supplies 80% of blood to the scaphoid via retrograde flow

- Superficial palmar arch (branch of volar radial artery)

Classification of scaphoid fractures

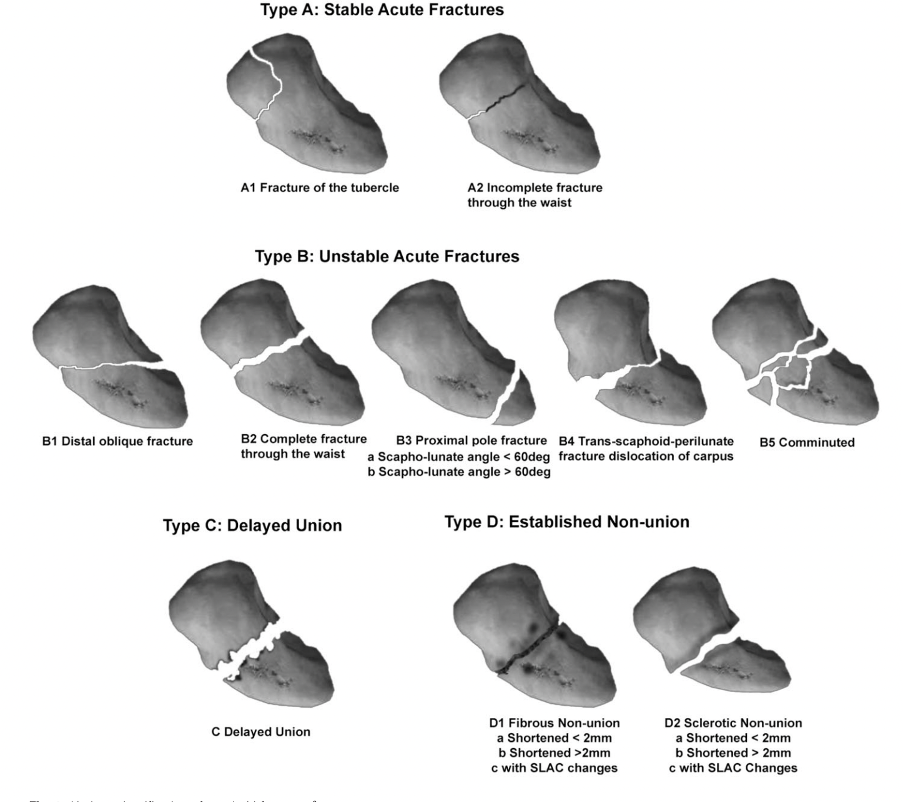

The Herbert classification is the most commonly used classification system (Figure 1). It divides acute fractures into stable (type A), unstable (type B), delayed unions (type C), and established non-unions (type D).1,2

Tubercle fractures (A1) and incomplete waist fractures (A2) are both classified as stable.1,2

Unstable fractures include distal oblique fractures (B1), displaced or complete waist fractures (B2), proximal pole fractures (B3), fracture-dislocations (B4), and comminuted (B5).4

Risk factors

Male patients between 15 and 29 years have the greatest risk of fracturing the scaphoid. This can be attributed to the increased likelihood for the young male age group to engage in high-velocity activities.3

Scaphoid fractures are not specifically associated with other risk factors or pre-existing conditions.

The following risk factors are associated with an increased likelihood of scaphoid non-union:2

- History of osteonecrosis

- Nicotine use

- Delay in diagnosis

- Proximal pole fracture

- Displacement greater than 1mm

- Vertical oblique fracture pattern

- Inadequate immobilisation

Clinical features

History

Scaphoid fractures are typically associated with a history of a fall on an ulnar-deviated, pronated, and outstretched hand.

However, patients may also present with a history of direct trauma to the scaphoid or after axial loading to the wrist in neutral extension-flexion.2

Typical symptoms of a scaphoid fracture include:1

- Deep, dull radial wrist pain

- Wrist swelling

- Decreased range of motion

- Decreased grip strength

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Clinical features of neurovascular compromise (see below)

- History of the fall: loss of consciousness, previous episodes, and/or other injuries

- Past medical history: previous falls, previous fractures, history of osteonecrosis, co-morbidities

- Medication history: any medications contributing to the fall (e.g. antidepressants, diuretics, sedatives, beta-blockers)

- Family history: family history of fractures and/or falls

- Social history: smoking (a risk factor for non-union), alcohol or illicit drugs (risk factors for falls), occupation (may influence management choice), physical activity and exercise (associated with higher incidence for scaphoid fracture)

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to the assessment, investigation and management of falls.

Neurovascular injury

It is important to ask about symptoms suggesting neurovascular injury since this is fairly common in scaphoid fractures. Scaphoid fractures can cause median nerve damage and/or lead to avascular necrosis.

Relevant symptoms include the 3Ps:

- Pallor (suggesting vascular injury)

- Pain disproportionate to the injury (suggesting compartment syndrome)

- Paraesthesia (suggesting nerve injury)

Clinical examination

A thorough examination of the hand and wrist should be conducted when a scaphoid fracture is suspected. An upper limb neurological examination should also be performed to rule out neurovascular compromise.

Any patient with the following clinical examination findings should initially be treated as having a scaphoid fracture until proven otherwise:2, 6

- Scaphoid tubercle tenderness volarly

- Anatomical snuff box tenderness dorsally

- Pain on axial compression of the thumb

Each finding has a sensitivity of approximately 87-100%, with a specificity of approximately 74% when all tests are positive within 24 hours of injury.6

Other signs on clinical examination may include:

- Wrist swelling

- Haematoma, gross deformity, or ecchymosis (rare)

- Worsening pain on wrist circumduction

- Wrist range of motion decreased

Neurological findings

Although less common, median nerve damage can occur due to a scaphoid fracture. Therefore, the following median nerve functions should be assessed:

- Motor: ‘OK’ sign and grip strength

- Sensory: tip of the second digit (digital cutaneous branch) and thenar eminence (palmar cutaneous branch)

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses with similar presentations to a scaphoid fracture include:7

- Distal radius fracture

- Fracture of other carpal bone (e.g. trapezium fracture)

- Scapholunate dissociation

- Carpometacarpal osteoarthritis

- De Quervain tenosynovitis

- Tendonitis

- Trans-scaphoid perilunate dislocation

- Preiser’s disease (avascular necrosis of the scaphoid)

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations depend on the mechanism of injury and are part of the general assessment of a patient following a fall. These may include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): if a cardiac episode is suspected of having caused the fall

- Blood glucose: if a hypoglycaemic episode is suspected of having caused the fall

- Urine dipstick: if a urinary tract infection is suspected of having caused the fall

- Blood pressure (including lying and standing): to identify postural hypotension

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Baseline blood tests (FBC and U&E): if indicated as part of a general assessment following a fall

Imaging

Relevant imaging investigations include:8

- X-ray: AP, lateral and oblique views are required. A scaphoid view can also be used. This is performed by placing the wrist in ulnar deviation and extension.

- MRI: most sensitive imaging modality for diagnosing occult fractures. NICE guidelines recommend MRI as first-line imaging for suspected scaphoid fracture. However, X-ray remains the most commonly used first-line imaging technique due to the lack of MRI availability in the emergency department.9

- CT (coronal and sagittal plane reconstructions in the longitudinal axis): recommended if MRI is unavailable or for fracture classification, assessment of dislocation, and assessment of fracture healing. It is the preferred mode for determining non-union or incomplete union since primary bone healing is difficult to visualise on radiographs.

Management

Management of scaphoid fractures varies between hospitals. However, the following are evidence-based recommendations for managing scaphoid fractures.

Initial management10

Initial management of a scaphoid fracture includes:

- ABCDE assessment

- Analgesia: ranging from simple analgesia to strong opiates depending on the patient’s pain

- Immobilisation using a volar wrist splint, thumb spica splint, or cast until definitive imaging can be performed

Non-operative management10-12

Non-operative management depends on the anatomical location of the fracture:

- Distal scaphoid fractures and occult fractures: immobilisation using short-arm cast for 4-6 weeks

- Waist (midbody) or proximal (not proximal pole) fractures: immobilisation using short-arm cast for 10-12 weeks

Operative management10,11

Any open fracture or fracture associated with neurovascular compromise requires immediate surgical consultation. Indications for a surgical referral include:

- Delayed presentation (> 3 weeks post-fracture)

- Non-waist fractures with > 1mm displacement

- Waist fractures with > 2mm displacement

- If the patient has a waist fracture with ≤ 2 mm displacement and requests faster recovery than expected with non-operative management.

- Fractures of the scaphoid proximal pole

- Fractures with an associated scapholunate ligament injury

- Carpal instability

Surgical fixation involves open or percutaneous insertion of K-wires or screws. The open approach is preferred for non-unions and grossly displaced fractures.

Follow-up

There is no specific guidance regarding the follow-up of scaphoid fractures. However, generally, X-rays are repeated at two weeks. If healing cannot be visualised, a CT is usually performed.

Return to activity11

All patients should be informed about predicted functional recovery, rehabilitation, and guidance on when to resume regular activities, including work, education, and driving.

- Patients should not return to full activities until clinical and radiographic union has occurred

- If clinical/radiographic union is present, patients should wear a rigid splint for two months while participating in strenuous activities following cast removal.

The average time to return to full activity (including non-contact sports) after non-operative management of a non-displaced fracture is approximately 11 weeks.

The average time to return to full activity after surgical management of scaphoid fractures is approximately six weeks.

Rehabilitation

Early rehabilitation is critical to preventing stiffness and non-union. Rehabilitation includes the following:

- Physiotherapy: flexion and extension of the fingers and wrist, thumb opposition, pinch grip, thumb abduction

- Smoking cessation

- Appropriate cast care

Complications

Complications of scaphoid fractures include:7

- Non-union (the most common complication)

- Malunion

- Delayed union

- Avascular necrosis

- Scapholunate dissociation

- Osteoarthritis

- Stiffness

Key points

- Scaphoid fractures are the most common form of carpal bone fracture, typically following a fall onto an outstretched hand (FOOSH).

- All patients with snuffbox (scaphoid tubercle) tenderness and/or radial wrist pain should initially be treated as having a scaphoid fracture due to the high index of non-union in untreated and undertreated scaphoid fractures.

- The most commonly affected patient population is male patients aged 15-29 involved in high-velocity activities.

- Scaphoid fractures can be classified as stable (type A), unstable (type B), delayed union (type C), and established non-union (type D) based on the Herbert classification.

- Typical clinical features of a scaphoid fracture include dull radial wrist pain, wrist swelling, decreased range of motion, and decreased grip strength.

- Initial management involves analgesia and immobilisation of the wrist.

- Definitive management depends on the timing of presentation and classification. It involves immobilisation for 4-12 weeks or surgical fixation using K-wires or screws.

- Specific complications include malunion, scapholunate dissociation, avascular necrosis, stiffness, or osteoarthritis.

Reviewer

Dr Alexander D. Vara

Hand and Upper Extremity Surgeon

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Sendher, R., & Ladd, A. L. (2013). The scaphoid. Orthopedic Clinics, 44(1), 107-120.

- Fowler, J. R., & Hughes, T. B. (2015). Scaphoid fractures. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 34(1), 37-50.

- Garala, K., Taub, N. A., & Dias, J. J. (2016). The epidemiology of fractures of the scaphoid: impact of age, gender, deprivation and seasonality. The bone & joint journal, 98(5), 654-659.

- Hickey, B., Hak, P., & Logan, A. (2012). Review of treatment of acute scaphoid fractures: R1. ANZ journal of surgery, 82(3), 118-121.

- Author. Herbert classification of scaphoid fractures. Published in 2012.

- Clementson, M., Björkman, A., & Thomsen, N. O. (2020). Acute scaphoid fractures: guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. EFORT open reviews, 5(2), 96.

- Hayat, Z., & Varacallo, M. (2021). Scaphoid wrist fracture. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- Dean, B. J., & SUSPECT study group. (2021). The management of suspected scaphoid fractures in the UK: a national cross-sectional study. Bone & Joint Open, 2(11), 997-1003.

- NICE. Fractures (non-complex): assessment and management. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK].

- BMJ Best Practice. Wrist Fractures. Published in 2022. Available from: [LINK].

- Up To Date. Scaphoid Fractures. Published in Available from: [LINK].

- Snaith, B., Walker, A., Robertshaw, S., Spencer, N. J. B., Smith, A., & Harris, M. A. (2021). Has NICE guidance changed the management of the suspected scaphoid fracture: a survey of UK practice. Radiography, 27(2), 377-380.