- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

A volvulus is defined as a twist of a segment of the bowel around its mesenteric attachment and, thus, its blood supply. The sigmoid colon is a common area of volvulus in the gastrointestinal tract alongside the caecum.

This article will focus on sigmoid volvulus, including the anatomy, clinical features, investigations and management options.

Aetiology

The sigmoid colon is a common area for volvulus to occur, as it is a relatively ‘floppy‘ piece of bowel that can twist on its mesentery and subsequently cause large bowel obstruction.

This can result in a degree of ischaemia and, in severe cases, perforation. It can occur spontaneously but usually requires a chronically distended sigmoid colon, as seen in those with chronic constipation.

Anatomy and pathophysiology

The sigmoid colon is a floppy piece of bowel, and its mesentery can resemble a fan shape. The mesentery is broad and far spread at the mesenteric border of the bowel, but as you chase it to its attachment, it becomes narrower. It is this narrow section where the mesentery can twist on itself.

As the mesentery carries the blood supply to that section of the bowel, when a volvulus occurs, the blood supply is threatened. The bowel, with time, will become ischaemic.

Ischaemia leads to the mucosa breaking down, and gut flora can translocate into the gut wall. This can result in necrosis and eventual bowel perforation.

Furthermore, as the bowel has twisted on itself, a closed loop large bowel obstruction occurs. This is when the proximal contents of the gastrointestinal tract cannot move into the obstructed section, and the contents of the obstructed section cannot move distally. This increases the risk of perforation.

Risk factors

Risk factors for sigmoid volvulus include:

- Elderly patients

- Male sex

- Previous episodes of sigmoid volvulus

- Reduced mobility

- Chronic constipation

- Neurological disorders

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of sigmoid volvulus include:

- Lower abdominal pain: often colicky or spasmodic; this pain can be more severe in late presentations and cases of perforation

- Abdominal distension

- Constipation (inability to pass stool) or obstipation (complete constipation, inability to pass wind and stool)

- Vomiting: however, this is usually a late presentation and is associated with large bowel obstruction

If perforation is present, the patient may present with septic shock (hypotension, tachycardia and pyrexia).

Clinical examination

Typical findings on abdominal examination include:

- Abdominal distention: on percussion, this will be tympanic

- Tenderness on palpation of the lower abdomen

- If perforation is present, there will be guarding present with a rigid abdomen

There may be a large capacious rectum on rectal examination.

Differential diagnoses

It is important to consider other causes of large bowel obstruction when presented with a patient with abdominal distention and pain.

Differential diagnoses to consider include:

- Colorectal malignancy: for example, sigmoid cancer resulting in large bowel obstruction. This usually presents with a more chronic picture with ‘red flag’ symptoms such as a change in bowel habit, bleeding per rectum, tenesmus (feeling of incomplete rectal emptying), or an abdominal mass. There may be constitutional symptoms (e.g. weight loss, night sweats). A CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast would be indicated.

- Paralytic ileus: this may be after surgical inventions and presents with a distended abdomen and acute change in bowel habits. This occurs due to a lack of peristalsis and reduced gut motility, and it is classed as a ‘pseudo-obstruction’

- Toxic megacolon: this is a complication of an acute flare of colitis (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease or other pathologies), whereby the large bowel becomes acutely inflamed, dilated and at risk of perforation. This history is acute and presents with severe abdominal pain with pyrexia, tachycardia and potentially sepsis.

Investigations

Beside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- A stool chart

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count (FBC)

- Urea and electrolytes (U&E): patients can have hypokalemia and other electrolyte disturbances

- C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Serial venous blood gasses (VBG): to assess for lactate and its trend (lactate can indicate ischaemia)

Imaging

Relevant imaging investigations include:

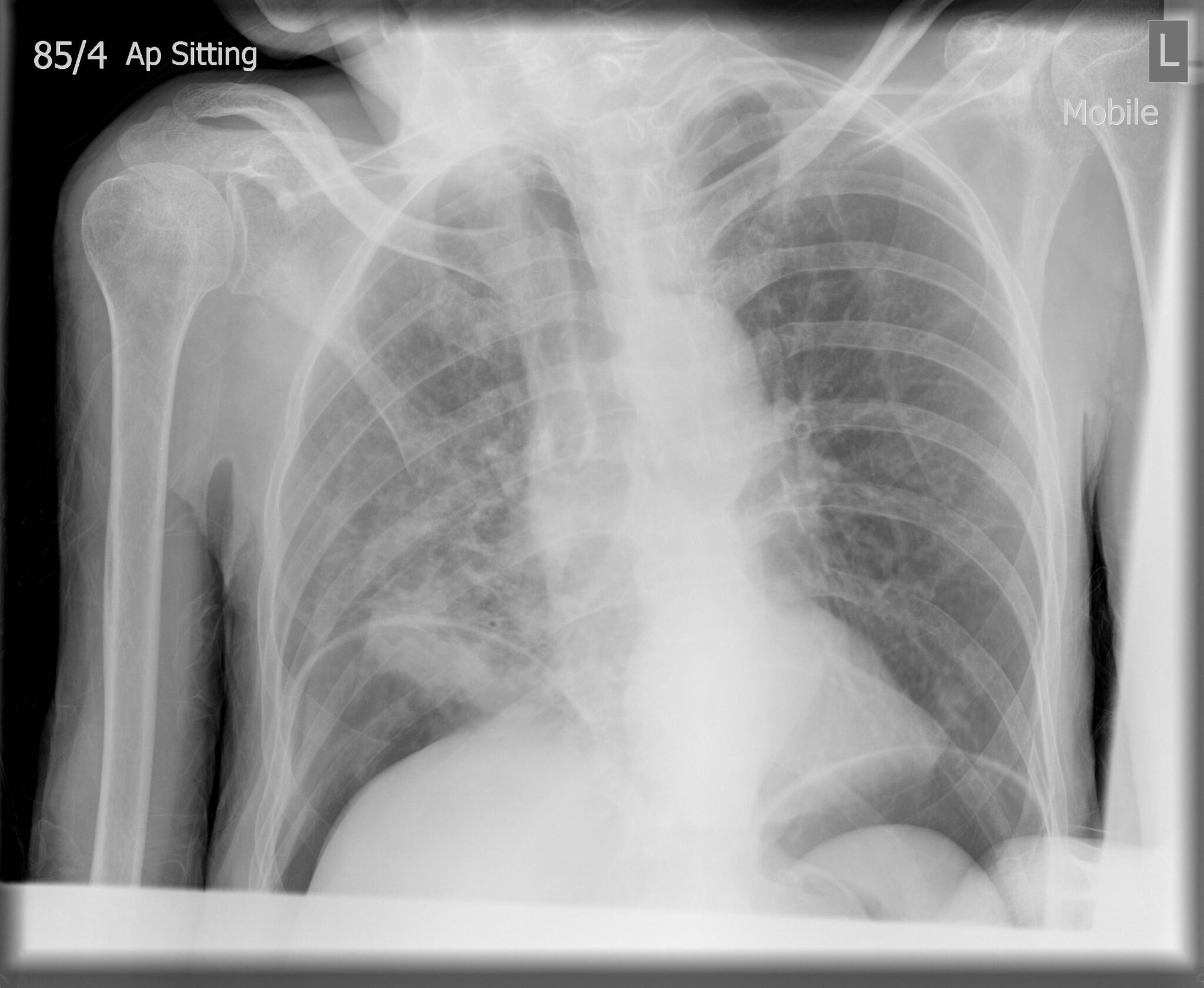

- Abdominal X-ray: this will typically display a characteristic ‘Coffee Bean’ sign. Rigler’s sign (indicating free air in the abdomen) may be present if perforation has occurred

- Erect chest X-ray: this will help rule out any air under the diaphragm (pneumoperitoneum) if perforation is present

- CT abdomen pelvis with contrast: this will define the volvulus; however, volvulus is normally diagnosed on abdominal X-ray

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of sigmoid volvulus can be reached with a history and typical examination findings. Furthermore, a coffee bean sign on an abdominal X-ray is diagnostic.

Management

Acute management

Acutely unwell patients who are shocked due to perforation require an ABCDE approach, with resuscitation and stabilisation.

Patients are often hypovolaemic and have concurrent hypokalemia (this can be rapidly identified by taking a venous blood gas). Therefore, fluid resuscitation with potassium will aid fluid status and help treat electrolyte disturbances.

If the patient is vomiting, a Ryles tube should be inserted to aid gastrointestinal decompression and the patient should be nil by mouth (NBM).

Decompression

Most patients can be treated with decompression using a rigid sigmoidoscope and by placing a flatus tube.

If the sigmoidoscope or the flatus tube passes the twist, an immediate rush of wind and liquid faeces is released. As the contents are emptied via the flatus tube, the abdomen should begin to decompress and reduce in size.

The flatus tube can be left in situ to allow for further decompression.

If the sigmoid volvulus is not decompressed despite these efforts, a formal flexible sigmoidoscopy can requested and performed by an endoscopist.

Surgical management

If the patient is acutely unwell and displaying clinical or radiological signs of perforation, the patient can undergo an emergency laparotomy and Hartmann’s procedure.

If the patient has multiple episodes of sigmoid volvulus, they may be offered a sigmoid colectomy. If the patient is not fit for surgery, they may be offered a percutaneous endoscopic colostomy (PEC), which involves placing tubes to vent a chronically over-inflated sigmoid colon

Complications

Sigmoid volvulus has a high risk of reoccurrence. This can result in repeated hospital admissions and increase the likelihood of obtaining a hospital-acquired infection, such as hospital acquired pneumonia (HAP).

If the sigmoid volvulus is left untreated and not managed promptly, gut wall ischaemia can occur. This, paired with gut flora translocation, causes gas formation, leading to perforation and peritonitis. This can lead to sepsis, septic shock and death.

Key points

- A sigmoid volvulus is a twist of the sigmoid colon on its mesentery, resulting in large bowel obstruction and ischaemia to the section of the affected bowel

- Typically, it occurs in elderly men, most of whom suffer from chronic constipation

- The most common clinical findings include lower abdominal pain and abdominal distention; a digital rectal examination will show a large capacious rectum.

- An abdominal X-ray may show the classic coffee bean sign.

- Medical management includes stabilising the patient if they are shocked and correcting any electrolyte disturbances.

- A rigid sigmoidoscope can inspect the mucosa and place a flatus tube under direct vision, allowing gas and liquid stool to pass. If this fails, a formal flexible sigmoidoscopy can be performed by an endoscopist for decompression.

- Surgical management includes an emergency laparotomy and Hartmann’s procedure if the patient is shocked due to perforation. Electively, the patient can be offered a sigmoid colectomy.

- Complications can include gut ischaemia, translocation of the gut flora, necrosis of the gut wall, and perforation, leading to septic shock and death.

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Longmore, J. Murray. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine. Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Atamanalp SS. Sigmoid volvulus. Eurasian J Med. 2010 Dec;42(3):142-7. doi: 10.5152/eajm.2010.39. PMID: 25610145; PMCID: PMC4261258.

Image references

- Figure 1. Case courtesy of Wael Nemattalla, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 10633. License: [CC BY-NC-SA]

- Figure 2. Case courtesy of Jeremy Jones, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 6129. License: [CC BY-NC-SA]