- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Sepsis can be defined as “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection”.1 It is a rare but serious response to infection, in which the body’s immune system goes into overdrive, setting off a cascade of negative consequences.

The incidence of sepsis is increasing. This is thought to be due to the ageing population, increasing multimorbidity, antibiotic resistance, and an increased emphasis on early recognition.2 In England, there were 200,000 admissions with sepsis in 2017/18.3 The mortality rate in England due to sepsis stands at 20.3%.4

Sepsis vs septicaemia

Sepsis is often confused with septicaemia, which refers to microbiological invasion of the bloodstream. Sepsis is a separate clinical entity that can occur in response to any infection, with or without septicaemia.

Risk factors

Risk factors for sepsis include:2,5

- Age <1 and > 75

- Frailty

- Impaired immune system: people on immunosuppressants, long-term steroids, chemotherapy, asplenia and other causes of immunosuppression

- Indwelling lines and catheters

- Intravenous drug users

- Severe burns

- History of invasive procedures in the last 6 weeks

- Women who are pregnant, have given birth or have had a termination of pregnancy or miscarriage in the past 6 weeks

Aetiology

Sepsis can occur secondary to any form of infection. The source of infection is most commonly bacterial; however, it can also be viral or fungal in origin.

Common sources of infection include:2,3

- Pneumonia (50%)

- Urinary tract (20%)

- Abdomen (15%)

- Skin, soft tissue, bone and joint (10%)

- Device-related infection (1%)

- Endocarditis (1%)

- Meningitis (1%)

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of sepsis is complex. In certain circumstances, the physiological immune response to an infection becomes deregulated for reasons that are not fully understood.6

Excessive cytokine release leads to a cascade of cellular changes that cause:

- Vasodilation

- Increased vascular (capillary) permeability

- Inappropriate activation of the coagulation cascade.

- Immune system impairment

Vasodilation leads to distributive shock, and the hypotension is worsened by hypovolemia secondary to excessive capillary leakage.

Inappropriate coagulation cascade activation leads to micro-emboli formation, which causes small vessel occlusion. These factors can rapidly lead to ischaemia of vital organ systems. If not quickly and appropriately managed, this can lead to multi-organ failure and, ultimately, death.

Tissue hypoperfusion/ischaemia can lead to different effects on the body’s various organ systems:2,6,7

- Central nervous system: confusion/delirium.

- Renal: reduced urine output, acute kidney injury

- Pulmonary: ventilation-perfusion mismatch leading to hypoxaemia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Cardiac: impaired myocardial function

- Gastrointestinal: ischaemic hepatitis, translocation of gut microbes into the bloodstream

Septic shock

Septic shock is defined as sepsis with hypotension that is not responsive to fluid resuscitation.

This will often be accompanied by the signs of organ dysfunction seen above, and serum markers of tissue ischemia will be raised (e.g. serum lactate). Septic shock represents advanced immune dysregulation, which is associated with increased mortality.

Clinical features

History

Due to its non-specific presentation, sepsis is notoriously difficult to diagnose by history alone.

Symptoms may initially relate to the source of the infection (e.g. dysuria in a urinary tract infection, productive cough in pneumonia). However, symptoms of sepsis tend to be extremely vague (e.g. increased confusion, feeling lethargic or generally unwell).

As such, sepsis should be considered a potential diagnosis in any unwell patient. A thorough clinical assessment should be undertaken to ascertain a patient’s risk/likelihood of sepsis.

Non-specific symptoms of sepsis may include:

- Fever symptoms (e.g. chills, rigors)

- Malaise and lethargy

- Confusion

- Myalgias

- Skin changes (mottling)

Symptoms specific to an infective source include:

- Respiratory: dyspnoea, productive cough

- Urinary: dysuria, urinary frequency and urgency, cloudy or foul-smelling urine

- Gastrointestinal: diarrhoea, abdominal pain

- Skin/soft tissue: skin redness (erythema) or heat (calor), joint pain/swelling

- Central nervous system: neck stiffness, photophobia, rash, confusion

Clinical examination

Clinical signs on examination may be generalised (secondary to the pathophysiology of sepsis) or related to the underlying infection.

General signs

General clinical signs of sepsis may include:

- Pyrexia (or hypothermia)

- Tachypnoea

- Tachycardia

- Hypoxia

- Hypotension, poor capillary refill

- Altered mental status

- Mottling of skin or ashen appearance

Specific signs

Clinical signs related to underlying infection may include:

- Respiratory: coarse respiratory crepitations, bronchial breathing

- Urinary: suprapubic tenderness, flank tenderness

- Gastrointestinal: abdominal distension, abdominal guarding/rigidity

- Skin / soft tissue: skin redness (erythema) / heat (calor)

- Central nervous system: reduced GCS, nuchal rigidity, papilloedema, positive Kernig’s sign

- Cardiovascular: new murmur, splinter haemorrhages

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Venous blood gas: assess lactate level (a key marker of tissue hypoperfusion)

- Capillary blood glucose: rule out hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia

- Electrocardiogram: rule out arrhythmias

- Urine dipstick: assess for the presence of a urinary tract infection (in certain populations)

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count: assess for neutrophilia or neutropenia (note neutropenic sepsis is a medical emergency)

- Urea and electrolytes: assess renal function

- Liver function tests: assess for liver dysfunction

- Coagulation profile: rule out coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- CRP: a non-specific marker of inflammation

Microbiological investigations

Relevant microbiological investigations include:

- Blood cultures: two peripheral sets, plus cultures from invasive lines if present

- Urine culture: to identify UTI and establish antibiotic sensitivities

- Viral swabs: including COVID-19

- Sputum culture: if productive cough is present

- Stool culture: if diarrhoea is present

- Lumbar puncture: if suspecting meningitis

Imaging investigations

Relevant imaging investigations include:

- Chest X-ray: to assess for pneumonia

- Ultrasound / CT abdomen: if suspecting intra-abdominal infection

- Echocardiography: if suspecting endocarditis

Management

All acutely unwell patients should be assessed using an ABCDE approach.

The key to managing sepsis is early recognition and early administration of antibiotics, alongside effective resuscitation. Any acutely unwell patient should be considered a potential case of sepsis.

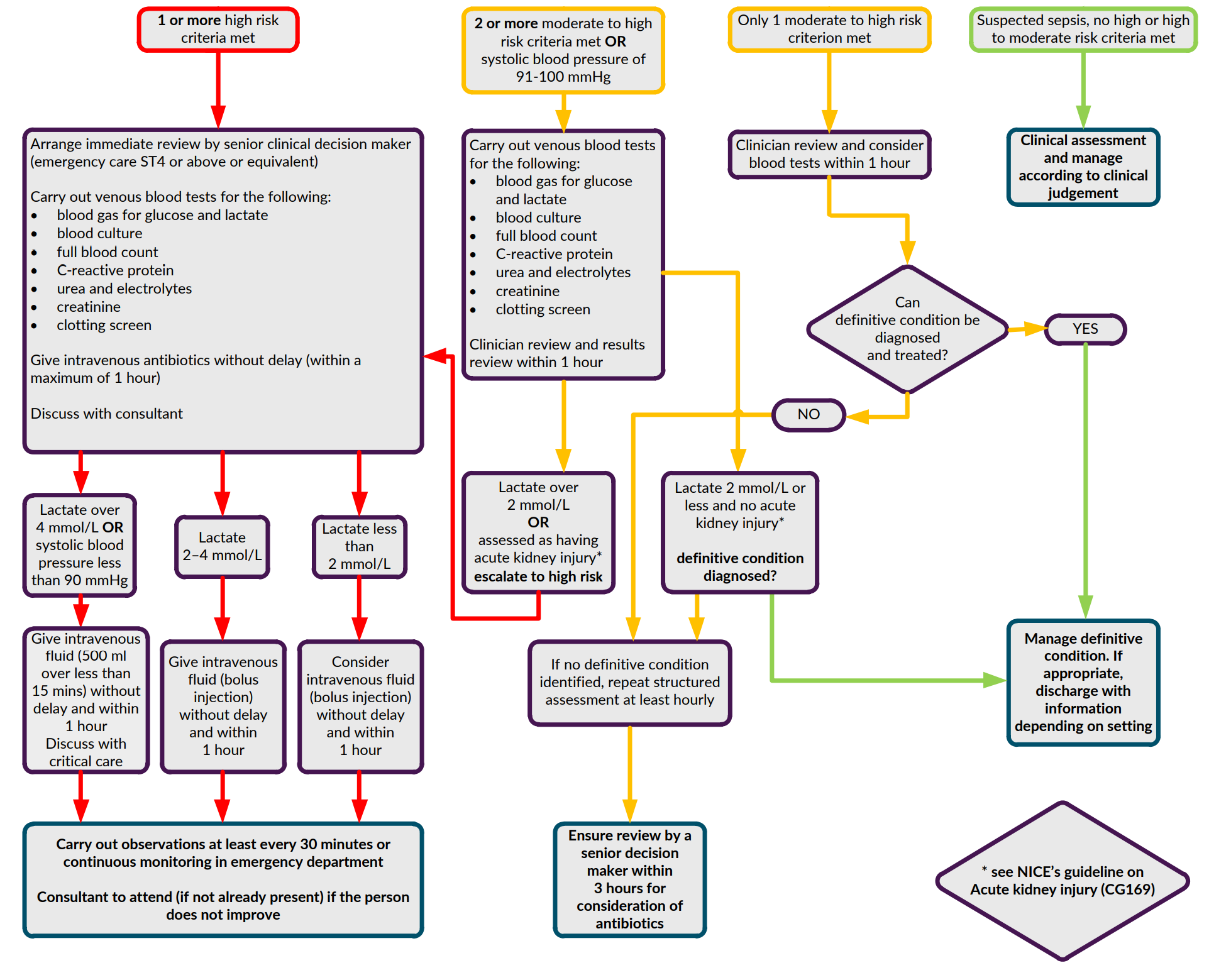

NICE guidelines

NICE now recommend using specific ‘red flag’ and ‘amber flag’ criteria to risk stratify and guide the management of patients with potential sepsis.

Patients with suspected sepsis should be assessed to see if any ‘red flag’ or ‘amber flag’ criteria are met, as these criteria are markers of severe disease needing urgent management.

High risk criteria (‘red flag’ sepsis)

Red flag criteria include:

- Behaviour: objective evidence of new alteration in mental state

- Heart rate: >130 beats per minute

- Respiratory rate: >25 breaths per minute or new oxygen requirement to maintain saturations

- Systolic blood pressure: <90 mmHg or more than 40 mmHg below baseline.

- Urine output: not passed urine in the previous 18 hours, or less than 0.5 ml/kg of urine per hour in catheterised patients.

- Skin: mottled appearance or Cyanosis or Non-blanching rash.

Moderate risk criteria (‘amber flag’ sepsis)

Amber flag criteria include:

- Behaviour: new onset altered behaviour or acute deterioration in function

- Heart rate: 91-130 beats per minute or new onset arrhythmia

- Respiratory rate: 21-25 breaths per minute

- Systolic blood pressure: 91-100 mmHg

- Urine output: not passed urine in the past 12–18 hours, or for catheterised patients passed 0.5–1 ml/kg of urine per hour.

- Temperature: tympanic temperature <36°C

- High-risk patients: immunosuppressed, recent (<6 weeks) trauma or surgery

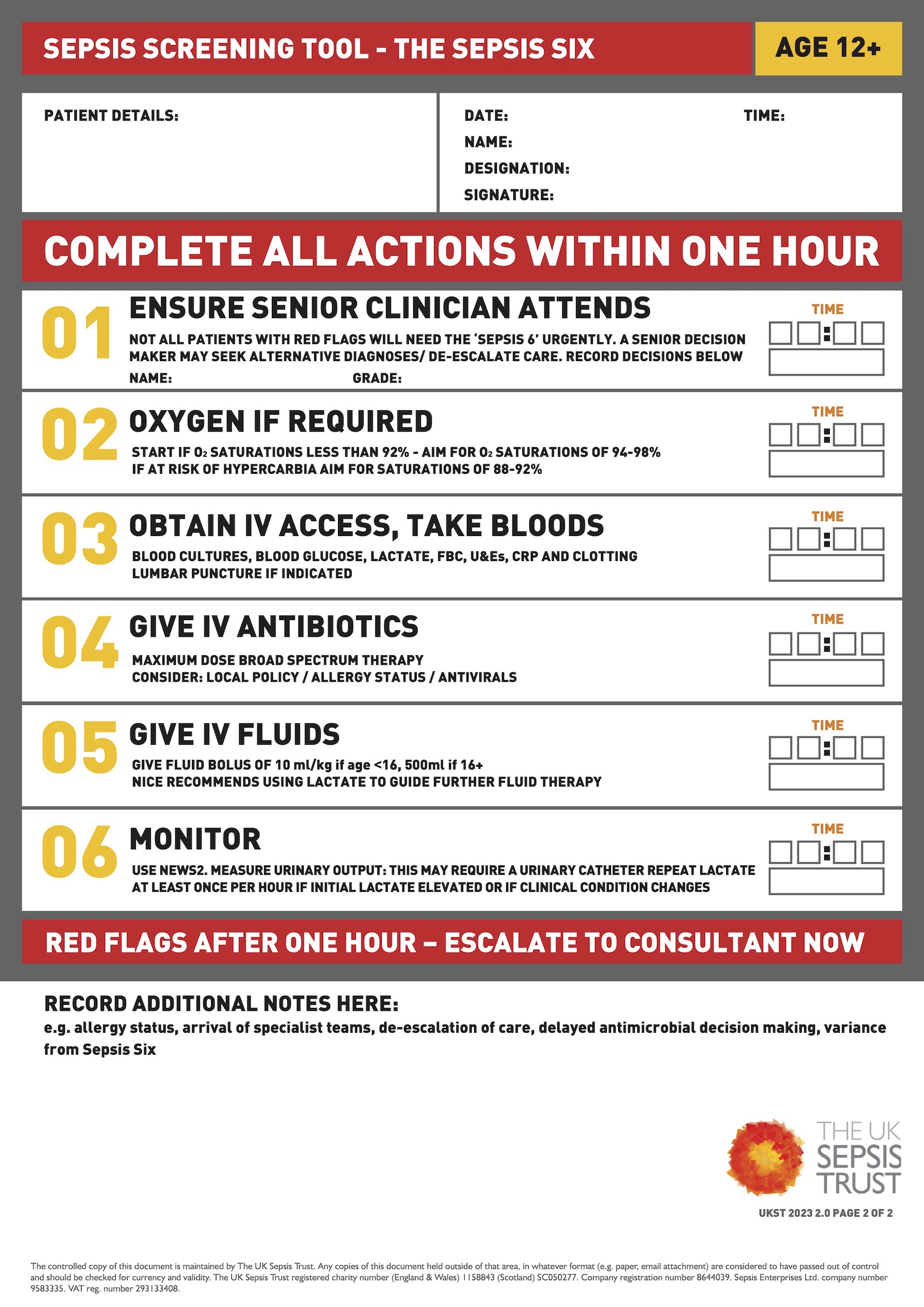

Sepsis six bundle

In the acute setting, any patients with suspected sepsis should be started on the sepsis six bundle as soon as possible (within one hour):

- Ensure senior clinician attends

- Administer high-flow oxygen if SpO2 <92%

- IV access & blood tests (blood cultures, lactate, FBC, U&E, CRP)

- Administer broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and consider source control

- Administer intravenous fluids

- Monitor urine output and lactate

Sepsis six mnemonic

You can remember the sepsis six using the acronym BUFALO:

- Blood Cultures

- Urine output

- Fluids

- Antibiotics

- Lactate

- Oxygen

Or, you can remember it by thinking of the steps as ‘taking 3 and giving 3’:

- Taking 3: blood cultures, lactate and urine output

- Giving 3: antibiotics, oxygen (to maintain SpO2 >94%), fluids

Once stabilised, infection source control is the next priority (e.g. chest physiotherapy in pneumonia, surgical referral if suspected intra-abdominal sepsis etc).

For patients with septic shock, vasopressor medications may be required to overcome severe vasodilation and hypotension. These patients should be admitted to a critical care environment and closely monitored.

Complications

Complications of sepsis include:

- Shock

- ARDS

- Myocardial dysfunction

- Acute/chronic renal injury

- Acute liver failure

- Multi-organ failure

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Death

- Post-sepsis syndrome

Key points

- The term sepsis refers to an inappropriate immune response that can occur secondary to any infective source

- Immune dysregulation causes a cascade of effects, including profound vasodilation and increased capillary permeability, leading to hypotension

- This process leads to hypoperfusion of multiple organ systems, such as the brain and kidneys. At worst, this can lead to multi-organ failure and death

- Any patients with suspected sepsis should be promptly started on the ‘sepsis six’ bundle, particularly if NICE ‘red flag’ criteria are met

- Each hour of delay in antibiotic administration increases mortality

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Singer, M., Deutschman, C. S., Seymour, C. W., Shankar-Hari, M., Annane, D., Bauer, M., … & Angus, D. C. (2016). The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). Jama, 315(8), 801-810.

- Gotts, J. E., & Matthay, M. A. (2016). Sepsis: pathophysiology and clinical management. BMJ, 353.

- UK Sepsis Trust. Sepsis Manual. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Burki, T. K. (2018). Sharp rise in sepsis deaths in the UK. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 6(11), 826.

- NICE. Sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management. 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Jarczak, D., Kluge, S., & Nierhaus, A. (2021). Sepsis—pathophysiology and therapeutic concepts. Frontiers in medicine, 8, 609.

- Hosein, S., A Udy, A., & Lipman, J. (2011). Physiological changes in the critically ill patient with sepsis. Current pharmaceutical biotechnology, 12(12), 1991-1995.