- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

This article covers the potential causes of an acutely painful red eye, including corneal abrasions and foreign bodies, corneal ulcers, chemical injury, anterior uveitis, scleritis, acute angle closure glaucoma and endophthalmitis.

These ophthalmological conditions typically require urgent specialist evaluation and management, so early recognition is essential.

Corneal abrasions and superficial foreign bodies

Small particles (metal, sand, organic material etc.) may result in a superficial abrasion to the cornea and/or conjunctiva. They may also become embedded superficially. It is important always to maintain a high index of suspicion for an intraocular foreign body.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to eye trauma.

The history will often confirm the likely source of the injury and may point to the possibility of an intraocular foreign body (for example, the use of power tools without eye protection). The patient will complain of ocular surface symptoms (pain, discomfort, grittiness, epiphora and photophobia). Visual acuity is unaffected unless the injury involves the visual axis (in front of the pupil).

Clinical examination

Typical clinical features using high magnification under a white light may include:

- Conjunctival hyperaemia: this may be focal and point to the area affected or diffuse

- A clear cornea with no areas of whitening (i.e. infection)

- Visible foreign body embedded in the conjunctiva or cornea: a metal foreign body embedded for several days will develop a rust ring around it

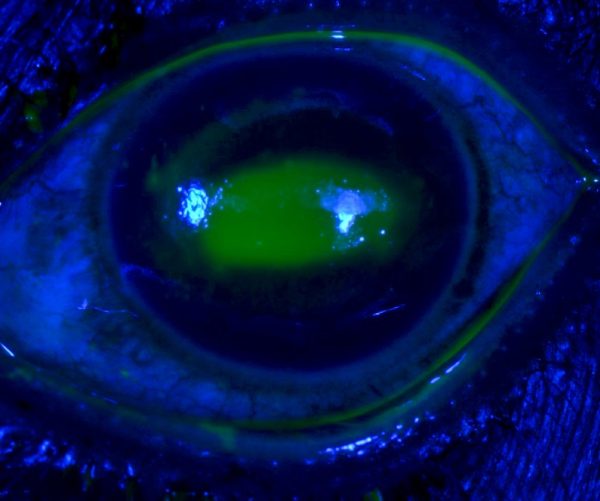

After instilling fluorescein 2%, under a blue light, areas of corneal or conjunctival epithelial injury will glow green. Abrasions may appear as large geographic areas of green staining or fine lines.

It is important to evert the lower and upper eyelid as foreign bodies may be embedded underneath. Linear vertical abrasions noted on examination suggest a foreign body embedded underneath the upper eyelid.

Microbial keratitis (corneal ulcer)

Microbial keratitis or corneal ulcer refers to sight-threatening infection and inflammation of the cornea. For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to keratitis.

Bacterial and viral keratitis represent the most common forms of microbial keratitis in the western world, but rarely the cause may be fungal or protozoan (acanthamoeba).

Contact lens wear is the most significant risk factor for keratitis. Any red eye in a contact lens wearer is keratitis unless proven otherwise. Other risk factors include ocular trauma, ocular surface disease (such as dry eye) and immunosuppression.

Clinical features

Corneal ulcers may initially present with similar symptoms to a corneal abrasion (e.g. pain, photophobia and visual acuity). These symptoms may then escalate, involving worsening pain and visual acuity.

Bacterial keratitis is associated with mucopurulent discharge, whereas viral aetiology presents with a clear discharge or watering.

Common examination findings include conjunctival injection with associated focal corneal haziness, representing the area of corneal inflammation. A corneal epithelial defect is almost always present, visible as an area of green uptake following fluorescein drops under cobalt blue light. A hypopyon may be present in severe cases.

The pattern of corneal involvement seen on examination can indicate the likely aetiology and is discussed in more detail in our keratitis article.

Management

Left untreated, corneal ulcers can cause rapid, permanent sight loss. Timely diagnosis of the aetiology of the corneal ulcer is key to initiating the correct treatment regimen, which may involve topical antibiotics, antivirals or antifungals. Systemic therapy may be used in severe cases.

Topical cycloplegics, oral analgesics and antiemetics should be prescribed to improve patient comfort.

Topical steroids should never be initiated by non-specialists as there is a risk of worsening the infection and corneal perforation.

Chemical injury

Chemical injury to the eye is an ocular emergency requiring prompt management. These may be accidental or secondary to assault.

Alkali burns tend to be more severe as it penetrates more deeply into the ocular tissues, whereas acids coagulate proteins, forming a protective barrier. Injuries involving ammonia and sodium hydroxide tend to be severe.

Any suspected chemical injury should be immediately irrigated until the pH neutralises, even before conducting any further examination. For detailed instructions on performing this, see the Geeky Medics guide to eye trauma.

Clinical features

Corneal and conjunctival chemical injury produces a similar constellation of symptoms as keratitis: eye pain, reduced visual acuity, photophobia and watering.

Typical clinical findings of a chemical injury on examination include:

- Conjunctival hyperaemia: this may be focal and point to the area affected or diffuse.

- Corneal haze: marked haze with an impaired view of the underlying iris and pupil implies severe injury. A clear cornea with an unimpaired view indicates milder injury and a better prognosis.

- Blanched blood vessels: areas of blanched blood vessels along the corneoscleral junction indicates limbal ischaemia.

After instilling fluorescein 2%, under blue light, areas of corneal or conjunctival epithelial defect will glow green.

Management

Prompt recognition and irrigation to remove any remaining chemicals are vital.

Supportive measures should be aimed at controlling pain and nausea via oral analgesics and antiemetics.

Chemical injuries with corneal epithelial injury, haze or blanched blood vessels should then be referred for specialist management. This involves topical and oral therapy aimed at reducing inflammation, preventing infection and promoting re-epithelialisation. Hospital admission and surgery may be required in severe cases.

Acute anterior uveitis

Uveitis is inflammation of the uveal tract, anatomically subdivided by the location into anterior (iris), intermediate (ciliary body and vitreous humour) and posterior subtypes (retina and choroid). Acute anterior uveitis is the most common subtype, and we will focus on this below.

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms are a red, watery eye that is photophobic with an associated dull ache. Visual acuity is also often mildly reduced. Unfortunately, these symptoms are relatively non-specific, with any insult to the cornea or conjunctiva resulting in a similar clinical presentation.

Clinical examination

Uveitis can be difficult to evaluate without a slit lamp however a pen torch examination can give clues towards this diagnosis.

Typical clinical findings on examination may include:

- Ciliary injection: dilated conjunctival vessels concentrated around the border of the cornea

- An irregular pupil: due to posterior synechiae (attachment of the iris to the lens capsule)

- Cloudy cornea and hazy view of the iris: due to cells in the aqueous humour and corneal oedema

- Hypopyon: an inferior settled layer of ‘pus’ (white cells and debris)

Some more specific signs found on slit lamp examination include:

- Keratic precipitates: fine cellular aggregates on the posterior corneal surface

- Cells: visible floating inflammatory cells in the aqueous chamber

- Flare: haziness of the aqueous fluid resulting from the breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier.

Causes

AAU can occur in isolation or be associated with multiple systemic conditions, including:

- HLA-B27 positive autoimmune conditions, such as psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis and Behcet’s disease

- Infectious causes, such as herpes simplex, herpes zoster, tuberculosis, syphilis and hepatitides

Management

Treatment aims to control inflammation, prevent visual loss and minimise long-term complications of the disease and its treatment.

Treatment commonly involves a slow tapering regime of topical steroids with cycloplegics under the care of ophthalmology. However, systemic immunosuppressant or antimicrobial treatment is occasionally required for the less common causes of uveitis.

Anterior scleritis

Clinical features

Anterior scleritis occurs on a spectrum ranging from trivial to sight-threatening disease. It tends to present with dull boring eye pain, headaches and epiphora. There may be painful eye movements and diplopia with accompanying myositis.

The affected area on the eye usually has a deep pink colour with a violet hue that is very tender to touch. There may also be dilated brighter red vessels superficial to these areas. Visual acuity can be affected. However, this is typically a late feature in severe scleritis or cases of posterior scleritis.

It is important to note that scleritis limited to the posterior aspect of the sclera may have all of the above features in the absence of a red eye.

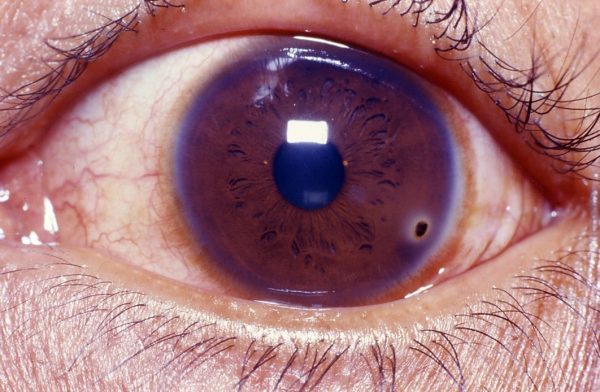

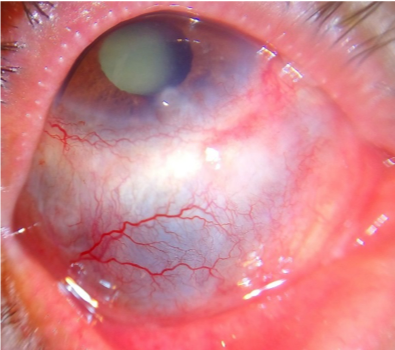

Scleritis can recur, resulting in thinning of repeatedly affected areas (as in the image below).

Scleritis vs episcleritis

Table 1. Comparison of the key features of scleritis vs episcleritis

| Episcleritis | Scleritis |

| Usually asymptomatic but may have mild grittiness and foreign body sensation | Frankly painful, tender to touch |

| Linked to systemic conditions (30%) | Linked to systemic conditions (50%) |

| Affected area is bright red | Affected area is deep red with a violet hue |

| Benign | Potentially sight-threatening |

| Self-limiting, topical treatments help | Requires systemic workup and treatment |

| No investigation | Investigate |

| Mobile vessels that blanch with phenylephrine 2.5% | Vessels are immobile and do not blanch with phenylephrine 2.5% |

| No areas of scleral thinning seen | Areas of scleral thinning seen if recurrent |

Causes

Scleritis is strongly associated (50% of cases) with underlying systemic rheumatological conditions.

Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common association. However, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, relapsing polychondritis, polyarteritis nodosa and Crohn’s disease are also common associations. Less commonly, scleritis can occur secondary to ocular surgery or infections (e.g. tuberculosis).

Management

All patients with scleritis should be investigated to exclude underlying autoimmune or infectious aetiology.

Management involves treating the underlying cause, which may involve high-dose steroids in rheumatological disease and antibiotics for infectious causes. Urgent referral to an ophthalmologist is required for all patients presenting with possible scleritis.

Acute angle-closure glaucoma

Acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG) is a condition of acutely raised intraocular pressure (IOP) associated with a physically obstructed anterior chamber angle. The ‘angle’ refers to that between the cornea and the iris where aqueous drainage takes place.

Clinical features

In AACG, there is an acute obstruction of aqueous outflow, resulting in the IOP rising rapidly.

AACG typically presents with deep ocular ache and headaches, which may be severe enough to induce nausea and vomiting. The visual acuity is reduced, and the patient may experience glare or ‘rainbows’ around light sources secondary to corneal oedema.

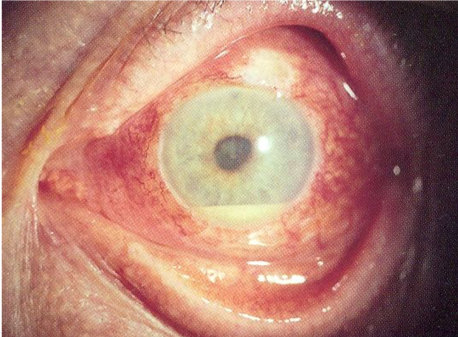

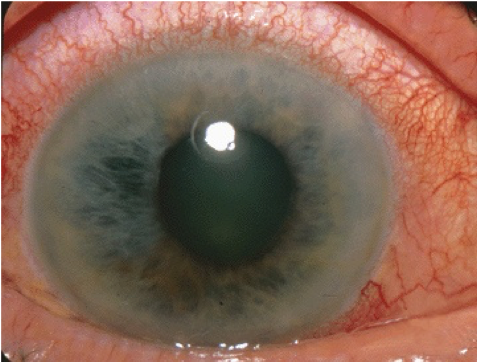

Typical clinical findings of AACG on examination are:

- Conjunctival injection

- Diffusely hazy cornea limiting view of the iris and pupil

- A fixed, non-reactive, mid-dilated pupil

- Very high intraocular pressure of >30mmHg

Management

Conservative measures that can be initiated by the non-specialist include oral analgesics and anti-emetics. The patient can be laid flat on their back (gravity helps bring the lens away and open the anterior chamber angle).

Specialist acute management of AACG includes:

- Systemic pressure-reducing agents: acetazolamide (IV/oral)

- Topical pressure-reducing agents (e.g. beta-blockers)

- Topical steroids to reduce inflammation

- Peripheral iridotomy (a laser hole through the iris) to allow a separate route for aqueous drainage other than through the pupil

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to acute angle-closure glaucoma.

Endophthalmitis

Endophthalmitis is an overwhelming infection of the internal structures of the eye that can result in permanent blindness and loss of the eye involved.

Causes

Endophthalmitis may be secondary to an exogenous source (e.g. following cataract surgery or intravitreal injection). It may be of endogenous origin, seeded from severe infections elsewhere (e.g. endocarditis or candida sepsis).

Clinical features

Patients typically present with severe pain, rapidly progressive visual loss, photophobia and floaters in the context of recent (<6 weeks) intraocular surgery or injection. Patients with endogenous endophthalmitis may be too unwell to report symptoms.

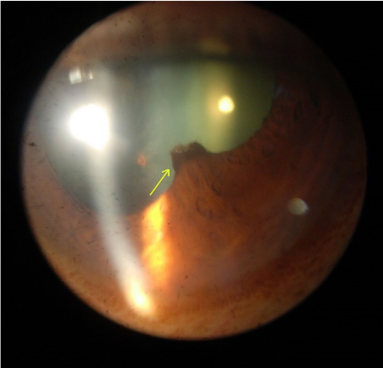

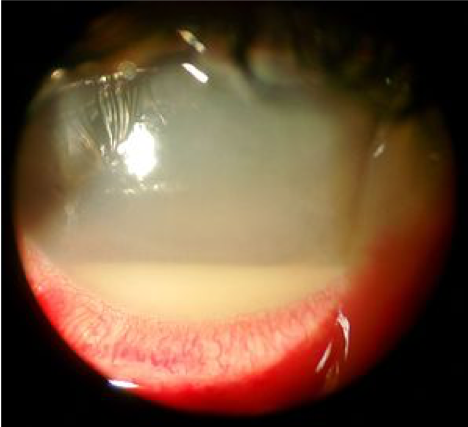

Typical clinical findings of endophthalmitis on examination include:

- Diffuse conjunctival injection

- Corneal haze with a limited view of the pupil and iris

- Hypopyon

- Relative afferent pupillary defect

Management

Endophthalmitis is a true ophthalmic emergency, and immediate specialist opinion should be sought.

Cases of suspected endophthalmitis require surgical intervention with sampling of vitreous fluid followed by injection of intravitreal antibiotics. Patients are admitted for topical and systemic therapy with close monitoring. Further surgery may be indicated depending on the presentation and clinical response.

Key points

- Moderate to severe eye pain and reduced visual acuity are red flags for serious ophthalmological conditions.

- There is a wide differential diagnosis for a red, painful eye. A detailed history and basic ocular examination can be used to identify conditions requiring urgent care.

Reviewer

Dr Ashley Simpson

Ophthalmology Registrar

Editors

Dr Chris Jefferies

Fiona Kirkham

References

- Community Eye Health Journal. A corneal abrasion glows green when stained with fluorescein and examined under a blue light. License: [CC BY-NC 2.0]

- Community Eye Health Journal. A metal foreign body that has been present for a few days has developed a surrounding rust ring. License: [CC BY-NC 2.0]

- Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa. License: [CC BY-NC-ND]

- Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa. License: [CC BY-NC-ND]

- EyeMD (Rakesh Ahuja, M.D.). Hypopyon. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Manimury. Posterior synechia. License: [Public domain]

- Imrankabirhossain. Recurrent scleritis. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Jonathan Trobe, M.D. AACG. License: [CC BY]

- Imrankabirhossain. Hypopyon. License: [CC BY-SA]