- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Pregnant people are at increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), and venous thromboembolism is an important direct cause of maternal death. When discussing VTE, this article will consider deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

Compared to people of the same age who are not pregnant, the risk of VTE increases between four and six times during pregnancy. However, the absolute incidence remains low, at about one in a thousand cases.

Aetiology

During pregnancy, the blood becomes more coagulable. This is due to:

- Increased coagulation factors VIII, IX and X

- Increased fibrinogen

- Decreased fibrinolytic activity

- Reduced anti-thrombin levels

- Reduced protein S levels

- Increased venous stasis

- Vascular damage

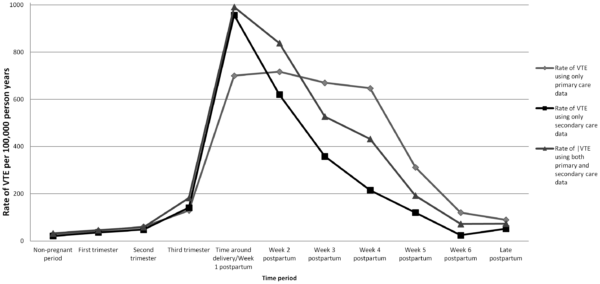

These changes can be considered protective against excessive blood loss at delivery. Accordingly, the risk of venous thromboembolism increases throughout pregnancy, peaks at the baby’s delivery, and slowly decreases back to baseline by six weeks postpartum (Figure 1).

The absolute risk of VTE is low during early pregnancy – however, this is when most fatal VTE events occur. As such, some form of early risk assessment is required to determine which women should be offered medications which can reduce the risk of VTE.

When managing people of child-bearing age with serious conditions such as mechanical heart valves or high-risk thrombophilias, conversations about how these conditions and pregnancy interact should be had as early as possible.

Use local prescribing guidelines for specific instructions, but risk factors are generally split into low, medium, and high groups. These algorithms are not yet standardised and can be frustratingly vague, so more research is needed.

Risk factors

Antenatal VTE risk factors

Table 1. Risk factors for VTE occurring antenatally.

| High risk | Medium risk | Low risk |

| Any previous non-provoked VTE | Immobility, e.g. due to prolonged hospital admission | BMI > 30kg/m2 |

| Mechanical heart valve | Dehydration, e.g. due to hyperemesis | Age > 35 |

| High-risk thrombophilia, e.g. antiphospholipid syndrome | Parity > 3 | |

| Medical co-morbidities, e.g. cancer, IBD, SLE | Smoking | |

| Surgery | Gross varicose veins | |

| Pre-eclampsia | ||

| History of unprovoked VTE in first-degree relative | ||

| Multiple pregnancy | ||

| In-vitro fertilisation or assisted reproduction |

Postnatal VTE risk factors

Table 2. Risk factors for VTE occurring postnatally.

| High risk | Medium risk | Low risk |

| Any previous VTE | Caesarean section during labour (i.e. not an elective case) | BMI > 30kg/m2 |

| Antenatal LMWH | BMI > 40kg/m2 | Age > 35 |

| High-risk thrombophilia, e.g. antiphospholipid syndrome | Admission/readmission for three or more days after delivery | Parity > 3 |

| Surgical procedure post-delivery (apart from repair of the perineum) | Smoking | |

| Medical co-morbidities, e.g. cancer, sickle cell anaemia, SLE | Elective caesarean section | |

| Family history of VTE | ||

| Gross varicose veins | ||

| Current systemic infection | ||

| Immobility, e.g. paraplegia, journey > 4 hours | ||

| Pre-eclampsia | ||

| Multiple pregnancy | ||

| Pre-term delivery (< 37 weeks) | ||

| Stillbirth in this pregnancy | ||

| Prolonged labour > 24 hours | ||

| Post-partum haemorrhage > 1L or requiring blood transfusion |

Clinical features

Signs and symptoms of DVT/PE in pregnancy are similar to those in non-pregnant patients.

History

Typical symptoms of a DVT include:

- Unilateral limb pain: often described as cramping and may worsen over several days

- Unilateral limb swelling

- Erythema

Typical symptoms of a PE include:

- Dyspnoea

- Tachypnoea

- Pleuritic chest pain

- Haemoptysis

- Concurrent symptoms of DVT

Clinical examination

Typical clinical signs of DVT on examination may include:

- Unilateral limb oedema: often pitting oedema

- Erythema

- Painful limb is warm to touch

- Peripheral venous distension

- Tenderness along the line of deep veins

- Painful movement of the muscles distal to the thrombus

Typical clinical signs of a PE on examination may include:

- Tachycardia

- Tachypnoea

- Hypoxia

- Low-grade fever

- Pleural rub

- Gallop rhythm: a wide split-second heart sound and tricuspid regurgitant murmur

If a patient develops a massive PE, they may present with haemodynamic instability, collapse and an elevated jugular venous pressure (JVP); this is a medical emergency.

Differential diagnosis

For more information on important differentials to consider in suspected VTE, see our articles on DVTs and PEs.

Investigations

VTE can be challenging to diagnose during pregnancy because symptoms such as shortness of breath and swollen legs are common; as such, objective investigations are necessary for diagnosis.

Clinical prediction rules developed for the non-pregnant population are not validated for use in pregnant people and should not be used. (e.g. Well’s Score)

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Basic observations: should be carried out on all patients with suspected VTE. Pulse oximetry during exertion can be useful in exacerbating the ventilation-perfusion mismatch and monitoring the resulting hypoxaemia.

- ECG: should be considered in suspected PE to help rule out differential diagnoses.

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count (FBC): may show a raised white cell count due to acute inflammation or help to rule out differential diagnoses

D-dimer

D-dimer is not indicated in pregnancy as it will give a false positive result.

Imaging

If DVT is suspected, patients will often be initiated on anticoagulation until imaging can be carried out; compression duplex ultrasound is the primary diagnostic test.

- If the ultrasound is positive, then anticoagulant treatment should be continued

- If the ultrasound is negative but clinical suspicion remains high, maintain the treatment and repeat the ultrasound on days 3 and 7

- If the ultrasound is negative and clinical suspicion is low, stop treatment

If PE is suspected but DVT is also suspected, investigate for DVT with compression duplex ultrasound. If it is positive, no other investigations are necessary, as the treatment for DVT and PE is the same.

If PE is suspected but without signs and symptoms of a DVT, a ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) lung scan or a computerised tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) should be performed.

These investigations involve radiation, and so there are concerns over the increased risk of developing cancer (foetal for V/Q; breast for CTPA). Explain to patients that these potential risks are extremely small. No large experimental studies have verified them; they have only ever been estimated.

Management

VTE prophylaxis in pregnancy

Patients should undergo a risk assessment early in pregnancy (and a re-assessment if their health changes significantly) and following delivery to determine whether prophylaxis is appropriate.

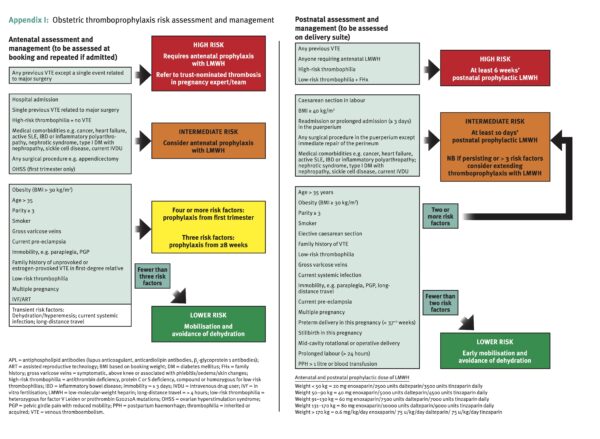

Guidelines for risk assessment may vary between hospitals, but the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has produced an example risk assessment that can be used (Figure 2).

VTE can be prevented with daily dosing of Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH). Local guidelines in your hospital set the particular version of LMWH and the weight-based dosage.

Other anticoagulants

Warfarin can cross the placenta and affect the growing foetus, so it is not usually appropriate in pregnancy. Direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are usually avoided due to the lack of reversal agents in case of bleeding.

In the acute setting, if the half-life of LMWH is considered too long, infusions of unfractionated heparin are an option.

Treating VTE in pregnancy

VTE is rare, but the risk of death plus the relative ease and safety of treatment means that there is a low threshold for treatment once there is a clinical suspicion. Start LMWH treatment dose and organise definitive radiological investigations as soon as possible.

VTE is often overlooked when pregnant people present outside of a traditional antenatal context, such as miscarriage or hyperemesis. It can also be neglected when pregnancy is detected incidentally. Consider VTE risk whenever managing a pregnant patient in the acute setting.

Treatment usually involves a once-daily, weight-based dosing of LMWH. Follow local guidelines. In non-standard cases, a haematologist may advise a twice-daily regime.

Due to the risk of dangerous haemorrhage, LMWH therapy should be stopped 24 hours before delivery. Practically, the patient should be advised that once they are in established labour, they should not self-administer any further medication.

LMWH is usually not restarted until 4 hours after the use of spinal anaesthetic or removal of the epidural catheter to reduce the risk of developing spinal haematomas.

Treatment in the puerperium

Any antenatal treatment should be continued until at least six weeks postnatally or three months in total, whichever is longer. As the baby is delivered, the risk to the foetus is eliminated, and the patient can decide to switch to oral medications such as warfarin, even if they are breastfeeding. There is less safety data regarding breastfeeding and direct oral anticoagulants, so seek expert advice and have careful discussions with the parents.

Postnatal presentation of VTE is common. VTE diagnosed within six weeks of delivery is considered provoked by the pregnancy and so would be managed with a three-month course of anticoagulation.

Complications

Complications of DVT and PEs are similar in pregnancy to the rest of the population and include:

- Sudden cardiac arrest: in the case of massive PE

- Acute limb ischaemia

- Post-thrombotic syndrome: residual pain, swelling and erythema. This can affect up to 30% of patients.

- Increased risk of recurrence

- Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH)

Future family planning

Any VTE diagnosed during pregnancy or the puerperium would count as a high-risk factor in future pregnancies and so call for antenatal treatment. It is pertinent to discuss this with the patient as it might affect their plans to expand their family.

Key points

- Venous thromboembolism is a leading direct cause of maternal mortality, however, the overall incidence is low

- Risk factor analysis in the early antenatal period is essential to detect high-risk individuals and prevent disease with effective prophylaxis

- If VTE is suspected as the diagnosis, start treatment as soon as the diagnosis is suspected, and request definitive imaging to confirm the diagnosis

- Due to increased risk of dangerous blood loss, avoid treatment during delivery, but restart as soon as it is safe

- Continue treatment until at least six weeks after delivery, or three months in total, whichever is longer

Reviewer

Miss Avni Batish MBBS, MRCOG

Editor

Dr Jess Speller

References

- Crosby, David A, et al. Antenatal venous thromboembolism. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 23.3 (2021): 206-212

- Reducing the Risk of Venous Thromboembolism during pregnancy and the Puerperium. Green-top Guideline No 37a. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (Great Britain). British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. April 2015.

- Bĕlohlávek J, Dytrych V, Linhart A. Pulmonary embolism, part I: Epidemiology, risk factors and risk stratification, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and nonthrombotic pulmonary embolism. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2013 Spring;18(2):129-38. PMID: 23940438; PMCID: PMC3718593.

Image references

- Figure 1. Abdul Sultan, A., Tata, L. J., Grainge, M. J., & West, J. (2013). The incidence of first venous thromboembolism in and around pregnancy using linked primary and secondary care data: a population based cohort study from England and comparative meta-analysis. PloS one, 8(7), e70310.

- Figure 2. Reproduced from: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Reducing the Risk of Venous Thromboembolism during Pregnancy and the Puerperium). Green-top Guideline No. 37a. London: RCOG, April 2015, with the permission of the College