- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Most doctors, especially those with limited paediatric experience, dread entering the paediatric emergency department (ED). However, it can be a very rewarding place to work!

The purpose of this guide is to demystify some of the common paediatric presentations so that you can confidently start your rotation. We will begin with a note on paediatric vital signs and the paediatric early warning score (PEWS) and cover everything from bumped heads and sore bones to wheezy kids, fevers and tummy pains.

Tip

You are not expected to be an overnight expert, and many departments will require you to discuss all patients during the beginning of your clinical rotation.

Top tips

Before we get going, here are a few top tips to bear in mind:

Listen to the nursing staff

Paediatric-trained nurses have a wealth of experience and are an incredibly valuable resource. Listen to their concerns. They will tell you if they think a child is unwell or if they have any safeguarding concerns.

Make the examination fun

Get down to the child’s level and try to use play and distraction when performing your physical examination.

Be opportunistic

Watch the child in the waiting room. Much information can be gleaned from simple observation (developmental stage, interaction with parents, range of motion). If the child is asleep, this can be a good time to listen to the chest and assess for respiratory distress.

Take concerns from parents seriously

Parents know their children better than you ever will. If they say something is wrong, you should listen to them.

Blood tests are often unnecessary

There isn’t the same knee-jerk reaction to performing blood tests in paediatrics as in the adult ED. Before requesting or taking bloods, ask yourself if it is necessary and whether it will change management.

Get help early

Children will compensate well for abnormalities in their physiology during the initial stages of an illness. However, they can also deteriorate rapidly when this physiological reserve runs out.

You should look out for tell-tale signs of circulatory compromise, such as tachycardia, tachypnoea, increased capillary refill time, decreased urine output and altered mental state. Never ignore abnormal vital signs, and get help early from a senior if you are concerned.

You are part of a team

Remember that you are not alone in the department. You will be working with senior doctors, paediatricians and skilled nursing staff. Always discuss your management plan with the nursing team. Communication is a key part of working effectively as a team.

Paediatric vital signs

The normal reference ranges for paediatric vital signs differ significantly between age groups. When assessing a child, you should check their vital signs against the age-appropriate reference range. Your department should have one of these visible around the main doctors’ hub. If not, printing and carrying a copy with you is worthwhile.

All doctors working in paediatrics, even those with years of experience, will occasionally refer back to a crib sheet of normal ranges.

You should pay close attention to the paediatric early warning system (PEWS) score. This score considers the age-adjusted paediatric vital signs and other factors such as the capillary refill time and respiratory effort.

Assessing respiratory effort

Assessing an unwell child’s respiratory effort is a key part of the paediatric examination. When assessing this, you should expose their chest and abdomen and look carefully for clues that indicate an increased work of breathing.

The following clinical features of mild, moderate and severe respiratory distress have been taken from the national paediatric early warning score in the UK for children between the ages of one and four:1

- Mild respiratory distress: nasal flaring, subcostal recession

- Moderate respiratory distress: head bobbing, tracheal tug, intercostal recession, inspiratory or expiratory noises

- Severe respiratory distress: sternal recession, grunting, exhaustion, impending respiratory arrest

Tip

You should always check a patient’s vital signs against the normal reference ranges for their age group and pay close attention to the paediatric early warning score (PEWS).

Assessing hydration and volume status

Assessing the hydration status of an unwell child is another critical component of the physical examination. Children are especially sensitive to dehydration secondary to diarrhoea and vomiting. Distributive shock in a septic child will also present with clinical features of hypovolaemia.

Clinical features

Clinical features of dehydration include:2

- Tachycardia

- Reduced skin turgor

- Reduced urine output

- Sunken eyes

- Dry mucous membranes

- Altered responsiveness

Clinical features of shock include:2

- Decreased conscious level

- Mottled skin

- Cold peripheries

- Prolonged capillary refill time

- Pronounced tachycardia and hypotension

Remember that children have a robust cardiovascular physiological reserve, meaning they will compensate well initially but may deteriorate rapidly. Hypotension is a very late sign. You should seek senior assistance early when treating children with signs of hypovolemia or shock.

Volume replacement

The Geeky Medics article on paediatric IV fluid prescribing provides more detailed guidance on the clinical assessment and fluid prescription in children.

Enteral fluids (oral or NG) are preferred for cases of mild to moderate dehydration. In contrast, IV fluids are needed for cases of severe dehydration and shock. Careful consideration should also be given to the cause of hypovolemia, including prompt administration of antibiotics in septic patients.

When treating non-critically unwell children with diarrhoea and vomiting, starting a fluid chart where regular sips of an oral rehydration solution or juice are given over time is helpful. You should expect clinical improvement as the child rehydrates, including wet nappies and normalising their vital signs.

WETFLAG

When preparing for the arrival of a sick child, it helps to have an idea of the doses of emergency drugs.

The WETFLAG mnemonic is used to remember the appropriate doses of drugs, fluids and electricity.

As a newcomer to the paediatric emergency department, you will not be expected to lead in the management of a critically unwell child. However, that does not mean you shouldn’t be a proactive and engaged team member. You can help by writing out the WETFLAG mnemonic on a whiteboard or flip-chart before the patient’s arrival.

Weight: estimated as (Age+4) x 2.

Energy: energy (joules) for cardiac arrest = 4 x weight (kg)

Tube: endotracheal tube size (cm) = (Age/4) + 4

Fluids: fluid bolus = 10mls / kg isotonic fluid (caution in some cases)

Lorazepam: 0.1mg / kg (max 4mg)

Adrenaline: 10mcg/kg (0.1ml/kg of 1:10000 solution)

Glucose: 2mls/kg (10% dextrose)

Minor injuries

Approximately 20-30% of paediatric emergency department presentations involve a minor injury or trauma.3 These include minor head injuries, wounds, soft tissue injuries and fractures.

When assessing a child with an injury, you should take a detailed history of the mechanism of injury. Pay attention to the interaction with the parents and whether or not the mechanism is in keeping with the injury.

Accidents do happen, but the possibility of a non-accidental injury should be at the back of your mind in any child who presents to the emergency department with an injury.

Minor head injury

Toddlers have a lot of energy and are not always very good at walking. This is a bad combination and a screaming toddler with a head injury is a common sight in the paediatric emergency department.

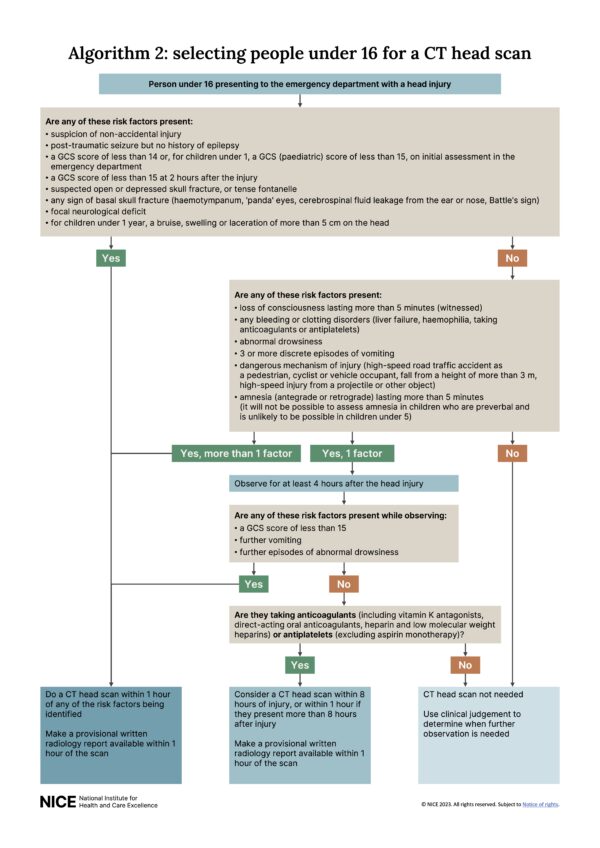

Most minor head injuries can be managed with glue, reassurance and discharge with head injury advice. However, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) have guidelines for considering a CT head in children.

The following features indicate an urgent CT head scan (within 1 hour).4

- Suspicion of non-accidental injury

- Post-traumatic seizure

- A GCS less than 14 on initial assessment or, for babies less than 1 year, a paediatric GCS score of less than 15

- A GCS score of less than 15 at two hours post injury

- Suspected open or depressed skull fracture or tense fontanelle

- Any sign of basal skull fracture (haemotympanum, ‘panda’ eyes, cerebrospinal fluid leakage from the ear or nose, Battle’s sign)

- Focal neurological deficit

- For babies less than one year, a bruise, swelling or laceration of more than 5cm on the head

Additionally, if any one of the following risk factors is present, they should be observed for a minimum of four hours post-head injury: three or more discreet episodes of vomiting, abnormal drowsiness, presence of a clotting disorder, dangerous mechanism, loss of consciousness over 5 minutes or amnesia over 5 minutes.

NICE recommends a CT should be performed within one hour if more than one of these features is present.

You do not have to commit these guidelines to memory but should refer to them whenever dealing with a child with a head injury.

Observation is itself a form of investigation

The threshold for performing a CT head in children is higher than that for adults due to the carcinogenic risk of high radiation exposure in a developing brain.

A child who looks unwell immediately following a minor head injury may be jumping around and playing in the waiting room four hours later. Holding onto them for observation is a better form of investigation than immediately reaching for a CT scan.

You should provide careful verbal and written head injury advice when discharging the child. This will include what to expect following a minor head injury and when to bring the child back for further assessment.

What to expect following a minor head injury

Common symptoms after a mild head injury include mild headache, tiredness, irritability, concentration problems and nausea.

When to bring your child back to the emergency department

Concerning features following a head injury include three or more separate episodes of vomiting (each vomit must be separated by 30 minutes to count as a new episode), seizure activity, persistent irritability despite pain medication, focal neurology or drowsiness.

Wounds

The best way of preventing an infection in a wound is to clean it thoroughly and remove any foreign bodies, such as grit and dirt, before closure.

Soft tissue X-rays can be requested if you suspect larger foreign bodies like glass.

Ensure the child has adequate analgesia before cleaning and closing a wound. Most departments will have access to an anaesthetic gel which can be applied to the area. Distraction and play are also very effective tools.

Specialist input may be needed in large wounds, wounds on the face or those which cross the vermillion border between the mucous membrane of the lips and the skin. This is because scarring in these areas can have significant cosmetic implications.

You should explore all wounds, making a note of any neurovascular compromise and whether or not there is tendinous or ligamentous involvement. If present, these may need to be repaired in theatre.

The technique chosen to close a wound will depend on the size, shape and location of the wound. Small lacerations with clean-cut edges that come together easily can often be closed with steri-strips or surgical glue. Larger or deeper wounds may require suturing.

Lacerations overlying an area of tension, such as a joint line, may also require suturing. Eventually, you will develop a feel for the best wound closure method. However, you should consult a senior if you are unsure of the best approach initially.

Tetanus

Tetanus prone wounds are those which have been exposed to tetanus spores (present in soil and manure). This includes puncture wounds, extensive burns, open fractures, animal bites and scratches. You should enquire about the immunisation status of all children with tetanus-prone wounds.

The UK Health Security Agency’s green book is an excellent resource that outlines which patients require a tetanus booster or tetanus immunoglobulin depending on the wound type and the patient’s immunisation status.5

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Routine prophylactic use of antibiotics for simple wounds is not recommended. However, antibiotics should be considered in human bites, animal bites and heavily contaminated wounds.

When discharging a patient, you should provide verbal and written wound care advice, including safety netting for signs of infection and information about when to remove their sutures.

Fractures

Children have more malleable bones than adults and are prone to incomplete fractures such as greenstick and torus (buckle) fractures:

- Greenstick fracture: an incomplete fracture where one side of the cortex is affected, but the bone does not break all the way through. This can be compared to when a green twig is bent and splinters on one side.

- Torus (buckle) fracture: An incomplete fracture with a small bump or buckle in the cortex of the bone. Commonly seen in the distal ulna and radius in children.

Picking up fractures on X-rays can be tricky if you are not used to doing this routinely. It is especially difficult in children where growth plates and ossification centres are thrown into the mix.

You should discuss any queries with a senior and get a second pair of eyes on the x-ray.

Most departments will have a policy for managing common types of fractures. This will often involve immobilising the bone in a cast, sling or splint and arranging follow-up in a fracture clinic.

However, some cases will need discussion with the orthopaedic team, such as compound (open) fractures, intra-articular fractures and fractures with significant deformity or neurovascular compromise.

In paediatric patients, you must be aware of fractures through growth plates, as these can affect the growth of the fractured bone.

The Salter-Harris classification is commonly used to describe the different types of growth plate fractures. This can be remembered by the mnemonic SALTR (slipped, above, lower, through and rammed).6

The Salter-Harris classification: SALTR

- I Slipped: fracture passes through the growth plate itself

- II Above: fracture extends above the growth plate (through the metaphysis)

- III Lower: fracture extends below the growth plate (through the epiphysis)

- IV Through: fracture extends through the metaphysis, growth plate and epiphysis

- V Rammed: a crush injury which compresses the growth plate

Elbow injuries

Injuries of the elbow are a good example of the complexities involved in interpreting X-rays in children. Here, we will go through the interpretation of an elbow x-ray as an example. Don’t worry – you will not be expected to become an overnight expert. Interpreting fractures in paediatric X-rays takes practice.

Supracondylar fractures are common in children, and you will frequently request elbow X-rays for a child who has fallen onto their arm.

Fat pads

Fat pads are hypodense shadows present around the joint, which indicate the presence of an underlying fracture.

An anterior fat pad in an elbow X-ray can be normal unless elevated in what is known as a sail sign. However, a posterior fat pad is always abnormal and suggests an underlying fracture.

Bone alignment

Two anatomical lines can aid in assessing the alignment of the elbow joint. These are the anterior humeral line and the radiocapitellar line.

Ossification centres

CRITOE is a commonly used mnemonic to remember the order in which the ossification centres around the elbow joint develop. The order itself is more relevant than the exact age:

- Capitellum: 1 year

- Radial head: 3 years

- Internal (medial) epicondyle: 5 years

- Trochlea: 7 years

- Olecranon: 9 years

- External (lateral) epicondyle: 11 years

If the ossification centre for the trochlea is seen, you should also notice the internal (medial) epicondyle ossification centre according to the CRITOE mnemonic. Following the mnemonic closely will ensure you don’t mistake an avulsed fracture of the internal (medial) epicondyle for the ossification centre of the trochlea.

Non-accidental injury

Emergency department staff play a vital role in detecting non-accidental injury (NAI) in children. Abuse can take many forms, such as physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse and neglect. It may be difficult to imagine these things happening, but they do.

Non-accidental injury should always be there at the back of your mind. Children in households where there is a history of drug abuse, violence or mental health problems in the family are at higher risk.

Make sure to ask whether or not the child is known to social services. Try to normalise asking this so that it forms a routine part of your history taking. Parents will understand that it is your job to look out for the welfare of your patients.

Suspicious features in the history and examination include:

- Vague or inconsistent history

- Physical examination inconsistent with the mechanism of injury

- Multiple ED presentations

- Delayed presentation

- Family history of violence or domestic abuse

- Child not interacting well with family

- Lack of parental concern or unusual parental behaviour

Burns and fractures are the most common type of physical abuse. Look out for suspicious burns such as immersion burns (where the child has been lowered into hot water) and cigarette burns.

Be wary of all fractures in non-mobile infants. The fracture should be consistent with the mechanism of injury and appropriate to the child’s developmental stage. You should be suspicious of any injury where the mechanism does not make sense, or the history is inconsistent.

Other suspicious injuries include:

- Bruising to the genitals, abdomen, buttocks, ears, neck and back of hands

- Injuries in the shape of a specific instrument, such as a belt buckle

- Multiple different types of injuries

- Sudden altered mental state which cannot be explained by a medical illness

Safeguarding

You should familiarise yourself with your hospital’s local safeguarding policy. Your first port of call should be the ED and paediatric consultants on-call. However, dealing with suspected NAI is multidisciplinary and may involve the police and social services as well as the hospital’s safeguarding lead.

The child may go on to have further investigations such as a skeletal survey, CT scan and ophthalmology review looking for retinal haemorrhages.

This is a difficult and emotional topic. The bottom line is that you should always consider NAI and discuss with a senior clinician if your suspicions are raised.

Fever in under 5s

A fever is a normal physiological response to an infection, and it is important to remember that it forms a natural part of the body’s defence mechanism.

You should not be concerned about the fever itself in a child who looks well. What is more important is how the child appears clinically.

One key exception to this is a neonate or a young infant (less than three months old) with a fever. Young infants with a fever are much more likely to have a concerning bacterial infection, and most departments advocate a full septic screen in a child less than three months who presents with a fever.7 The royal college of emergency medicine advises that all children under the age of one with a fever should have a consultant sign-off before discharge.

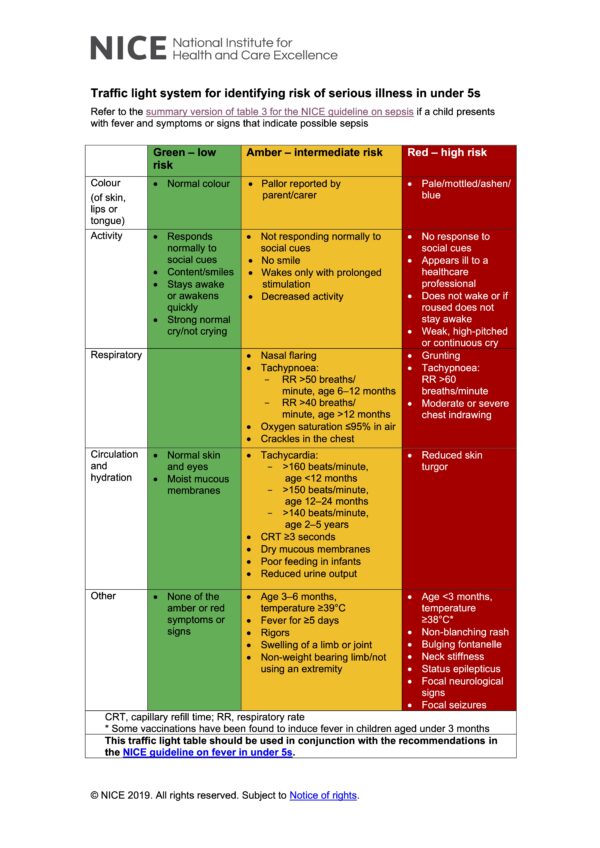

NICE traffic light system

If you take one thing away from this guide, it is to familiarise yourself with the NICE traffic light system for fever in under 5s.8

The guideline includes a table that divides patients into green, amber or red categories. It is an excellent resource that helps you risk stratify children presenting to the emergency department with a fever.

A classic example of a ‘green’ child is the toddler with a fever and a runny nose who looks well, with otherwise normal observations and is wreaking havoc in the waiting room. This child is likely to have a self-limiting viral illness and can be sent home with safety netting advice.

Amber signs include (but not limited to) abnormal vital signs, respiratory distress, decreased activity, poor feeding, reduced urine output and fever for more than 5 days.

Red signs in the traffic light scoring system include (but not limited to) mottled skin, decreased consciousness, focal neurology and signs of meningism.

Any child with amber or red features outlined in the traffic light scoring system should be discussed with a senior physician. Some departments have a rule that you should not discharge any child with abnormal vital signs, especially unexplained tachycardia.

Tachycardia will often go hand in hand with a fever. However, you should expect this to settle as the fever goes down with antipyretic medication such as paracetamol and ibuprofen.

Tip

Any child with an abnormal paediatric early warning score (PEWS) warrants a discussion with a senior ED or paediatric doctor.

Hunting for a source

When faced with a child with a fever, you should start thinking about the source. This can be difficult if the child presents early, as the source may take 24 hours or so to become clinically apparent.

A full ENT examination is key. The upper respiratory tract, including the ears, nose and throat, are the most common sources of viral and bacterial infections in children. If you have not had a good look at the throat and tympanic membranes of a child with a fever, you have not completed a full examination.

You will need the parents to help you secure the child on their lap before you can look at the tonsils.

It is often best to leave the ENT exam to the end of the physical examination as you will struggle to auscultate the chest or obtain an accurate heart rate after you have irritated the child with your tongue depressor!

Obtaining a urine sample is important in cases where the source is not obvious. Ask the paediatric nursing staff for tips on the best way to catch a fresh sample. This can be as difficult as it sounds.

Blood tests and imaging are rarely needed in children with a fever who have otherwise normal vital signs and are hitting a ‘green’ on all the traffic light scoring system components.

Prolonged fever with an unclear origin should prompt a discussion with the paediatric team for consideration of other causes.

Kawasaki disease is an example of a non-infective cause of a fever lasting for more than five days, which can result in cardiac disease such as coronary aneurysms in 20-25% of untreated cases.9

Febrile convulsions (seizures)

Febrile convulsions are relatively common in febrile children between six months and five years of age. They are thought to be associated with cases with a rapid rise in core body temperature. The classic presentation is a short-lived tonic, clonic seizure with a quick recovery phase in a febrile child.

Febrile seizures can be a scary thing for the parents (and ED staff) to witness. However, most cases are due to a self-limiting viral illness, and it is important to provide support and reassurance to the family.

Atypical seizures include those where there is a focal neurological element, a prolonged post-ictal phase or recurrent seizure episodes. You should consider an alternative cause in these cases (e.g. meningitis or encephalitis), and empirical treatment with antibiotics and antivirals pending further investigation by the paediatric team is indicated.10

Febrile seizures become less common as the child gets older. There is a chance of recurrence (approximately 33%), but most children will not have more than one episode. The chance of developing epilepsy after a simple febrile seizure is only slightly higher than that of the general population.

Following a febrile convulsion, it is important to consider the source of the fever. A child who is actively fitting should be managed with an ABCDE approach (don’t ever forget glucose!) following the advanced paediatric life support (APLS) seizure management guidelines.

As discussed above, the traffic light system can help risk stratify the febrile child. Blood tests are not routinely indicated following a febrile convulsion but should be performed in any child who appears unwell or where a focus cannot be found.

Wheeze

Wheezy kids are a common sight in the paediatric emergency department, and they normally fall into one of three categories: bronchiolitis, viral wheeze and asthma.

An overlap exists between these presentations, and other diagnoses can also present with a wheeze (e.g. fluid in the lungs of a neonate causing a wheeze due to a congenital heart defect).

Bronchiolitis

Bronchiolitis is usually caused by respiratory syncytial virus and typically presents in infants under two years of age.

The wheezing in bronchiolitis follows inflammation and fluid buildup in the small airways (bronchioles). The condition progresses over two to three days, with the worst symptoms typically appearing between days three and five.

Symptoms include cough, wheezing, increased work of breathing and difficulty feeding.

There is no specific treatment for bronchiolitis, and these patients are managed symptomatically.

X-rays and blood tests are unnecessary in mild/moderate cases, and bronchodilators such as salbutamol do not work in bronchiolitis.

Most cases are self-limiting and can be managed as an outpatient with careful safety netting advice.

However, patients taking less than half of their normal feeds or those with a decreased oxygen saturation or significant respiratory distress should be referred for inpatient paediatric input. You should also be aware of concerning features in the history, such as an ex-premature infant, the presence of comorbidities and blue, pale or floppy episodes.

Viral wheeze

Viral wheeze is common between 1-5 years of age. There is an overlap in the younger age group between viral wheeze and bronchiolitis. It is important to distinguish between the two as bronchodilators do not help with bronchiolitis but are indicated in cases of a viral wheeze. Ask your seniors for help in distinguishing between the two.

During your physical examination, look out for signs of respiratory distress such as increased respiratory rate, nasal flaring, grunting, tracheal tug, cyanosis, intercostal and subcostal recession and see-saw breathing (where the abdomen rises and chest wall draws in during inspiration).

It can be difficult to assess the respiratory effort in a child who is irritable and doesn’t like the look of you. The key to examining a child is to get them on your side, distract them with play and be opportunistic (e.g. assess respiratory effort while they are sleeping or observe them carefully when they are distracted).

Your department will have its own policy on managing viral wheeze in children. Salbutamol via a spacer (6-10 puffs) followed by observation is the starting point for most mild to moderate wheeze cases.

Children who require repeat doses of salbutamol more than four hourly will likely need admission. Those discharged can be sent home with a reducing regimen of salbutamol (check your department guidelines for the frequency).

Patients who fail to settle with the initial dose of salbutamol should go on to have ‘burst’ therapy, whereby multiple doses of bronchodilators are given over an hour. Nebulised salbutamol, steroids and oxygen therapy may also be required in severe cases.

You should seek help early in cases of viral wheeze which do not respond to initial treatment. Viral wheeze is a spectrum and some patients may become significantly unwell.

Asthma

It is rare for patients under five years to have asthma. It is more common for these children to have recurrent episodes of a viral wheeze rather than an underlying asthma diagnosis.11

Features which support a diagnosis of asthma include recurrent wheezy episodes, diurnal variation with symptoms being worse at night time, a history of atopy, low peak expiratory flow (PEF) or forced expiratory volume in 1 sec (FEV1) during symptomatic episodes and reversibility following treatment with a bronchodilator.12

Features of acute severe asthma include sats < 92%, PEF 33-50% best or predicted, an inability to complete full sentences, heart rate of over 125bpm in a patient over 5 and a respiratory rate of > 30/min in a patient over 5.

Features of life-threatening asthma include sats of <92%, a PEF of less than 33% best or predicted and any of the following: exhaustion, cyanosis, hypotension, silent chest, poor respiratory effort or confusion.

Treatment

Initial management of an acute asthma exacerbation in children includes the use of inhaled salbutamol via a spacer in mild to moderate asthma and nebulised salbutamol in severe cases. Ipatropium bromide should also be added in cases refractory to salbutamol. Dosing will depend on the severity of the attack and the patient’s response.

Oxygen saturations should be titrated with a face mask or nasal cannula to a target of 94-98%.

British Thoracic Society guidelines advocate for the early use of steroids for children with acute asthma exacerbations. Prednisolone (30-40mg) for three days is the typical dose for a child over the age of 5 who is not already on maintenance steroids.12

In severe and refractory cases, other treatment options include magnesium, IV salbutamol and aminophylline.

Tip

You should seek help early in all children with severe or refractory asthma as they can deteriorate quickly and may require a higher level of monitoring and treatment.

Croup

Croup, also known as laryngotracheobronchitis, is a viral upper respiratory tract infection typically affecting young children between 6 months to three years of age.

Parainfluenza virus is the most common causative organism, and children present with a characteristic ‘seal-like’ barking cough and stridor. Once you have heard it a few times, you can recognise the characteristic cough a mile away!

The Westley croup score is frequently used to assess the severity of the condition and guide treatment.13 Children with mild croup have the characteristic barking cough but no stridor at rest. Severe croup presents with significant stridor at rest and severe respiratory distress.

Mild to moderate cases can often be managed with a single dose of oral dexamethasone and a period of observation before discharge. More severe cases may need nebulised adrenaline and admission into hospital.

You should avoid overstimulating the child (including using a tongue depressor) in cases of croup with stridor to prevent worsening the symptoms.

The differential diagnosis of children presenting with stridor includes an inhaled foreign body and epiglottitis. This will normally be apparent in the history (e.g. sudden onset stridor with a history of choking or an unwell and ‘toxic’ looking child respectively).

Abdominal pain

In children, as with adults, there are many different causes of abdominal pain. However, children will often not give you a clear or reliable history of their presenting complaint.

The following are a few common conditions to consider while working through your differential diagnosis. This is not an exhaustive list and you should discuss with a senior or the on-call paediatric or surgical teams if specialist input is required.

Mesenteric adenitis

This is one of the most common causes of abdominal pain in children. The pain in mesenteric adenitis is secondary to inflammation of the mesenteric lymph nodes and typically follows an upper respiratory tract infection. Ask about recent infections and examine the ears, nose and throat of children presenting with abdominal pain.

Appendicitis

Appendicitis can occur at any age and typically presents with central abdominal pain, which migrates to the right iliac fossa. It is often accompanied by fever, nausea, vomiting and poor appetite. However, patients do not always present in a textbook way. You should carefully examine the abdomen for guarding in the right iliac fossa.

Constipation

Constipation is common in all ages. Try to obtain a detailed history regarding the child’s bowel habits: how often do they go? Is the poo hard? Does it hurt when they open their bowels?

It is also important to consider lifestyle factors such as diet as well as psychosocial factors such as anxiety or stress, as these are significant contributors to childhood constipation.

Urinary tract infection

UTIs are common and can present with lower abdominal pain in both children and adults. Ask about urinary frequency and dysuria. Wherever possible, you should obtain a urine sample in any child presenting with abdominal pain.

Testicular torsion

Don’t forget to examine the testicles in boys who present with abdominal pain. Pain in children can be poorly localised, and they may not tell you that it is their testicle which is hurting. Explain to the patient and the family why you are doing the examination. It is good practice to have a chaperone for intimate examinations.

Testicular torsion typically presents with an exquisitely tender, high-riding testicle and an absent cremasteric reflex. However, the presentation may not be typical, and you should urgently involve the urology team in all cases of suspected torsion. There is only a four to 8 hour window before significant ischaemic damage occurs!

Other causes of abdominal pain

There are many other causes of abdominal pain in children, such as gastritis, lower lobe pneumonia, diabetic ketoacidosis (remember to check blood glucose), intussusception, ovarian torsion, ectopic pregnancy, hernias and more.

Conclusion

This has been an introductory guide to common cases seen in the paediatric emergency department. We have covered an overview of minor injuries, safeguarding, fever in under 5s, wheezy children and abdominal pain.

However, this is just a taster of things to come. During your time in the paediatric ED, you will see many other presentations ranging from rashes and SVTs to pulled elbows and foreign bodies in ears and noses.

Remember to take concerns from the nursing staff seriously, do not ignore abnormal vital signs and discuss all cases you are unsure about with a senior doctor. Finally, don’t forget to enjoy yourselves!

References

- NHS England. National paediatric early warning system observation and escalation chart. 09/11/23. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Intravenous Fluid Therapy in Children and Young People in Hospital. Updated 11/06/20. Available from: [LINK]

- Kapur, A. RCEMLearning. Minor injuries. 12/09/2018. Available from: [LINK]

- National institute for clinical excellence (NICE). Head injury: assessment and early management. 18/05/2023. Available from: [LINK]

- The UK Health Security Agency. The Green Book: tetanus (chapter 30). Updated 01/06/22. Available from: [LINK]

- Murphy, A. Radiopaedia. Salter Harris classification. Revised 30/01/23. Available from: [LINK]

- Copp, F. RCEMLearning. A child with a fever. 12/09/2018. Available from: [LINK]

- National institute for health and clinical evidence (NICE). Fever in under 5s assessment and initial management. Updated 26/11/21. Available from: [LINK]

- McCrindle, B.W. et al. AHA journals: Circulation. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. 29/03/17. Available from: [LINK]

- Messahel, S. RCEMLearning. Paediatric seizures – PEM induction. 11/12/2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Abela, N. RCEMLearning. RCEM blogs – PEM starter pack. 12/09/2018. Available from: [LINK]

- British Thoracic Society. BTS/SIGN guideline for the management of asthma. July 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Klassen, T. MD+Calc. Westley croup score. Accessed Dec. 2023. Available from: [LINK]