- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

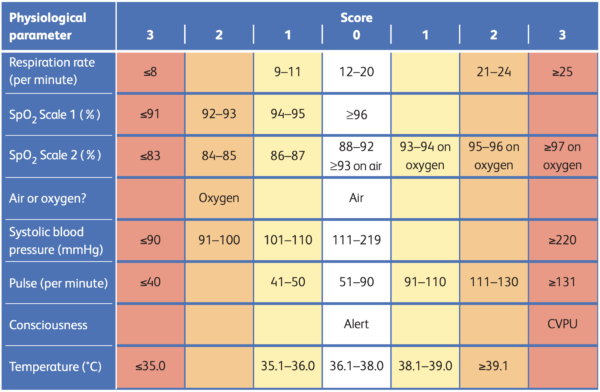

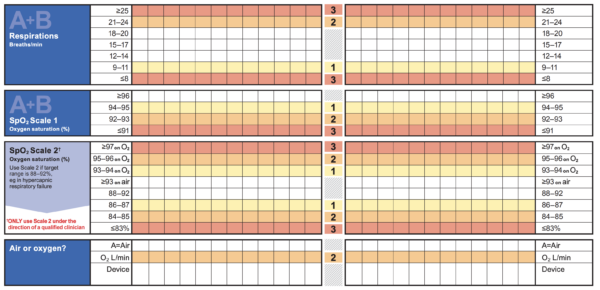

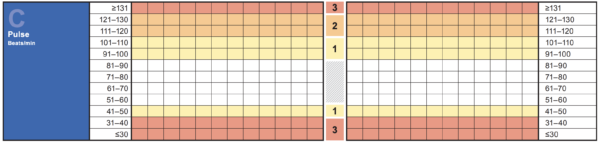

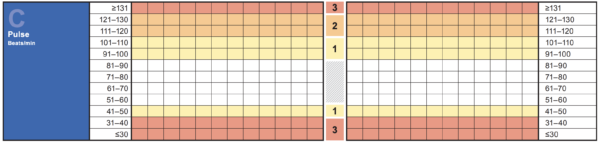

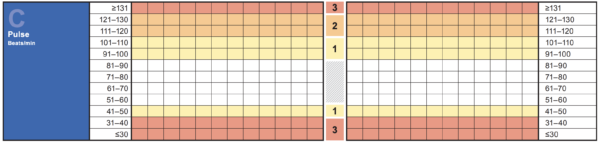

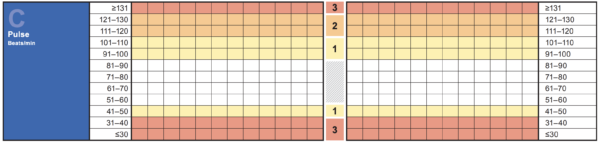

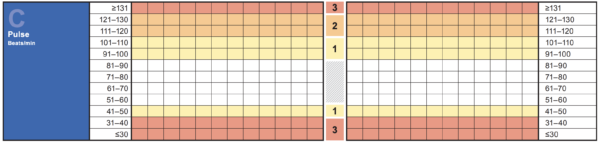

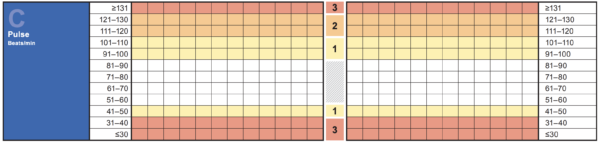

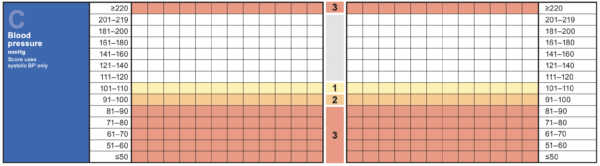

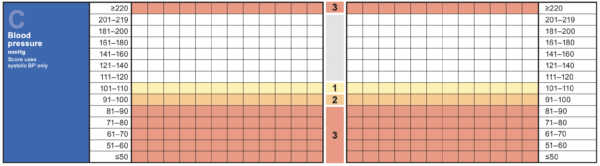

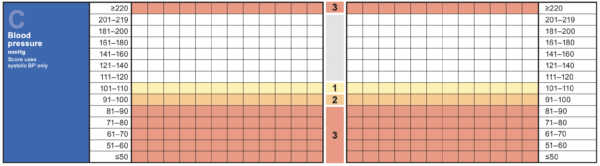

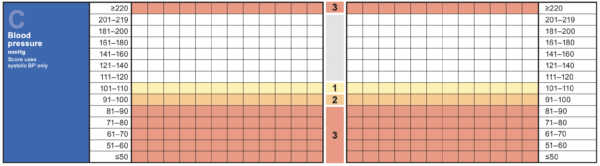

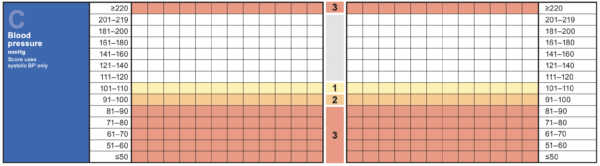

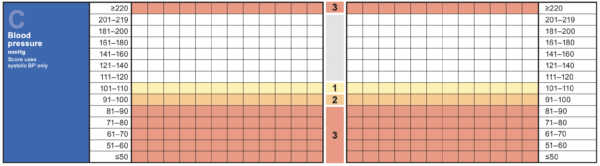

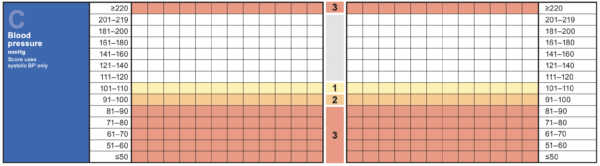

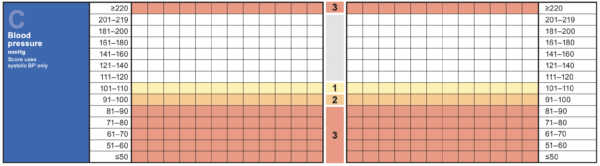

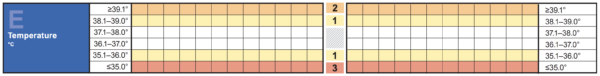

When working on-call, you will frequently be asked to review patients with abnormal observations and high NEWS (National Early Warning Score).

NEWS is a track-and-trigger system which tracks observations to identify patients at risk of deterioration. Nursing staff will escalate patients with a high NEWS for a medical review.

This guide will cover how to approach reviewing patients with abnormal observations and aims to give helpful initial tips and considerations when assessing these patients.

Respiratory distress and hypoxia

Common causes

- Pulmonary embolism

- Acute heart failure / fluid overload

- Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)

- Aspiration

- Exacerbation of underlying lung disease: asthma / COPD etc

- Acid-base disturbance (e.g. diabetic ketoacidosis, tachypnoea to compensate for metabolic acidosis)

Triage

When triaging a patient with hypoxia or respiratory distress, the two key things to determine are:

- The acuity/severity of oxygen requirement

- The level of respiratory distress

Most of this information can be gathered by reviewing the trend in observations. For example, a patient admitted with a respiratory condition who has had an increase in oxygen requirement from 1 to 2 litres and no significant increase in respiratory rate can most likely safely wait for assessment while you finish your current tasks.

On the other hand, a patient who is admitted without a known respiratory illness who has a new oxygen requirement and tachypnoea will need a more urgent assessment.

Any patient with significant new tachypnoea (generally RR >25) and/or new oxygen requirement (generally hypoxia to <91% in the absence of COPD) will meet the criteria for an emergency call.

Assessment

From the end of the bed, assess the patient’s respiratory rate, work of breathing and oxygen requirement.

If the patient is comfortable, with a low oxygen requirement (low-flow nasal cannulae), it is reasonable to gather more information from the patient’s notes before assessment.

If the patient is working hard to breathe or requires a face mask / high-flow nasal oxygen to maintain their oxygen saturation, it is best to perform an initial ABCDE assessment to assess clinically for the likely cause.

The history will often give clues as to the diagnosis, i.e. a confused or frail patient that desaturates after dinner or an episode of choking is likely to have aspirated, a febrile patient may well have developed hospital-acquired pneumonia (although remember PE is an important cause of fever).

Examination should first ensure no airway issues (anaphylaxis/angioedema) and then initially focus on the cardio-respiratory system as per the ABCDE algorithm. It is important to consider the above common causes during the examination:

- Is the JVP raised with significant pedal oedema? (consider heart failure)

- Is there a unilateral hot swollen leg? (consider DVT/PE)

- Is the chest wheezy? (consider COPD/asthma)

Oxygen should initially be given at whatever flow rate necessary to restore a patient to their target oxygen saturations. If the patient looks unwell and you are struggling to get a good oxygen saturation, always start with 15L via a non-rebreather mask.

Always remember that certain patients predisposed to CO2 retention may have lower oxygen saturation targets (e.g. in COPD). However, it is always safer to aim for a SpO2 >94% whilst gathering more information if this is unclear.

Investigations

Key investigations to consider include:

- ECG: is there any evidence of cardiac ischemia or any signs suggestive of PE?

- ABG / VBG: is this suggestive of type 1 or type 2 respiratory failure? What is the acid-base status of the patient?

- Blood tests: assess infection markers, consider D-Dimer only in certain clinical scenarios where pulmonary embolism is suspected (discuss with senior).

- Portable chest X-ray: is there evidence of pneumonia or fluid overload?

- CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA): if the suspected underlying diagnosis is PE (discuss with a senior).

Management and escalation

In any patient with an acute change in respiratory function, it is important to have a clear diagnosis and treatment plan (e.g. anticoagulation in PE, diuresis in acute heart failure). If you are unsure of the cause of hypoxia after the above assessment and initial investigations, always discuss the patient with a senior doctor.

Patients with markedly increased work of breathing (tachypnoea, tracheal tug, intercostal recession) are at risk of tiring, and should have critical care review regardless of oxygenation status. Any patients with significant oxygen requirement (>4L low flow nasal prongs) should also be escalated to the critical care team in case of further deterioration requiring ventilatory support.

It is important to re-assess the patient during the shift to ensure response to treatment. If the patient is not getting better despite treatment, the diagnosis should be re-considered or treatment escalated.

If your shift is ending, it is important to hand these patients over to the oncoming team for ongoing review.

Tachycardia

Common causes

- Arrhythmia (e.g. rapid atrial fibrillation, SVT)

- Hypovolemia*

- Fever/sepsis*

- Pulmonary embolism*

- Pain/agitation*

*These pathologies will all most commonly cause a sinus tachycardia, but can also cause arrhythmias (e.g. rapid AF) in predisposed patients.

Triage

Triaging patients with tachycardia can be difficult, as knowing the rhythm is a very important part of this process, which can generally only be done by visualising the ECG. Other important factors to consider are the rate of tachycardia and whether this is acute or persisting.

A mild tachycardia (<110) that has been persistent throughout the admission is most likely related to the underlying disease state requiring hospitalisation. It is unlikely to require urgent review in the absence of other concerning features or nursing concerns, and thus, these patients can be seen as time allows.

A new tachycardia is always abnormal and warrants early review. The key is to assess over the phone for any signs of adverse features that could be associated with tachycardia, specifically hypotension, chest pain, syncope or hypoxia (heart failure). These features indicate haemodynamic compromise from decreased cardiac output in the setting of a tachycardia. If any adverse features are present, this warrants escalation to an emergency call and urgent attendance.

Further information can be gleaned from the rate itself, with tachycardias <110 more likely to be sinus tachycardia and tachycardias >130 much more likely to be a tachy-arrythmia. Again, this can only really be confirmed by ECG analysis. In most hospitals, a tachycardia >130 will meet the criteria for a medical emergency call.

Whenever you are called to see a tachycardia, ask the ward staff to perform a 12-lead ECG and, if possible, to have it by the bedside for your arrival.

Assessment

On arrival to the ward, eyeballing the patient in conjunction with the ECG is always useful.

In a well-looking patient with otherwise normal observations and sinus tachycardia on the ECG, there will be more time to review the patient’s medical notes before assessment, which may give clues as to the underlying diagnosis (e.g. admission with profuse diarrhoeal illness, possible hypovolemia).

If the patient has a sinus tachycardia but looks unwell from the end of the bed, perform an ABCDE assessment to look for the underlying cause (e.g. febrile / peripherally dilated in sepsis, chest pain/hypoxia in PE, dry mucous membranes in hypovolemia).

If there is a tachyarrhythmia present on the ECG, this requires urgent management. A quick ABCDE assessment to assess for adverse features is important. However, it is important to recognise that these patients can deteriorate quickly, even in the absence of initial adverse features. It is reasonable to get senior help early and ensure you are prepared for deterioration (e.g. obtain IV access, placing the patient on a cardiac monitor).

Most tachyarrhythmias are associated with a ventricular rate fast enough to warrant an emergency call – so it is unlikely that you will be left alone in these situations!

Resuscitation Council guidelines

The Resuscitation Council (UK) provide excellent guidelines on the initial management of tachyarrhythmias, including a management flowchart to follow.

Investigations

Key investigations to consider include:

- ECG: assess rhythm

- VBG: assess pH/lactate

- Blood tests: consider underlying cause/electrolyte disturbances

Management and escalation

Tachyarrhythmias should be managed according to the underlying rhythm, as per the resuscitation council guidelines. These situations should be led by senior members of the medical team or members of the critical care team.

The key to managing a patient with sinus tachycardia is to find and treat the underlying cause.

In the case of sepsis/hypovolemia, IV fluid boluses to restore circulating volume should successfully bring down the tachycardia, alongside treating the underlying condition.

If you cannot find and treat an underlying cause, always escalate to a senior colleague to discuss the case – it is often prudent to exclude PE in cases where no other cause can be identified.

Bradycardia

Common causes

- Bradyarrhythmias

- Acute myocardial infarction

- Medication-induced (beta-blockers, digoxin)

- Normal variant (young/athletic patients)

Triage

The key to triaging a patient with bradycardia is to assess for the presence of adverse features (as per tachycardia triage – hypotension, chest pain, syncope or myocardial ischemia). These can represent inadequate cardiac output secondary to the bradycardia and thus require an emergency response.

The second thing to consider is the rate of bradycardia. Bradycardias >50 with no adverse features are relatively common overnight and can generally be triaged at a lower priority (although it is important to ensure that the nursing staff have actually woken the patient up to confirm this assessment!).

Having said this, it is still necessary to check the rhythm. Ask the nursing staff to perform a 12-lead ECG and place the patient on cardiac monitoring before your arrival, and of course, to call if there are further concerns.

A heart rate <50 increases the chance of a bradyarrhythmia; these patients should be seen more urgently. Again, ask for cardiac monitoring and a 12-lead ECG before your arrival.

Assessment

On arrival to the ward, look at the patient from the end of the bed for any clear signs of adverse features before examining the ECG. If the patient looks unwell or you are concerned, perform an A-E assessment and follow the resuscitation council’s bradycardia algorithm.

If there are no signs of adverse features, reviewing previous observations to see if this is new or old is helpful, as new bradycardia is of greater concern.

Review the drug chart for any culprit medications (beta-blockers, digoxin, rate-limiting calcium channel blockers). If the patient presented with symptoms in keeping with the above adverse features (e.g. chest pain, syncope) without another clear cause, this is worthwhile to note as it may indicate a risk of deterioration, even if the patient is currently well.

When assessing the patient, ask about any previous episodes of these symptoms and whether they are currently symptomatic.

Investigations

Key investigations to consider include:

- ECG: assess the rhythm

- VBG: assess the lactate, which will be raised if inadequate cardiac output is associated with bradycardia.

- Blood tests: check electrolytes, and consider a troponin level in a patient with new bradyarrhythmia, especially if significant cardiac risk factors or risk of silent-MI. Always send a digoxin level if the patient is on digoxin therapy and becomes bradycardic.

Management and escalation

A patient with sinus bradycardia and no adverse features can generally be observed. However, they will initially need to be placed on telemetry / cardiac monitoring to monitor and ensure no there are high-risk features (e.g. prolonged ventricular pause).

Patients with high-risk brady arrhythmias on the ECG (e.g. complete heart block, Mobitz type II AV block) may require transcutaneous pacing due to the risk of asystole.

These patients should be urgently discussed with senior on-call doctors and the critical care team. Consider a bolus dose of 500mcg atropine IV whilst awaiting senior support if you are concerned that adverse features are developing.

Hypertension

Common causes

- Primary (essential) hypertension

- Secondary hypertension (e.g. renal artery stenosis, phaeochromocytoma)

- Neurological disturbance (e.g. intra-cerebral haemorrhage, raised intracranial pressure)

- Missed medications

Triage

The key to triaging hypertensive patients is to ascertain the presence of symptoms and the severity of blood pressure rise.

If the patient has symptoms that could be related to hypertension (e.g. chest pain, severe back pain, headache, confusion, visual disturbance), these patients should be urgently assessed. This is especially true if the blood pressure is >180/120, which would meet the criteria for a hypertensive emergency (BP >180/120 & symptomatic).

If the BP is <180/120 and the patient is asymptomatic, these patients can generally await your review when time allows. Hypertension >180/120 is of greater concern, even if the patient is asymptomatic, as many hospitalised patients will be at risk of end-organ damage with blood pressure at this range (‘hypertensive urgency’).

It is worth asking over the phone if a patient is normally on anti-hypertensives in the community and if these have been skipped or are due soon. Giving a patient’s missed medication (or regular medication early) is often acceptable as a first-line treatment. If the BP falls to an acceptable range following this with no symptoms, they may not require a formal out-of-hours review.

Assessment

When assessing a patient with hypertension, the key is a thorough history. Asymptomatic patients are unlikely to need a full ABCDE assessment. Take a systematic history of current symptoms to ensure no signs of end-organ dysfunction, particularly chest pain, headache and visual disturbance.

Patients with chronic blood pressure problems are often very aware of their treatment journey and their own ‘normal’ limits. Ensure that there are no other medical problems that may require tight BP control (e.g. recent intra-cerebral haemorrhage, or known aneurysms).

A neurological examination is important to ensure there are no localising neurological deficits that would need urgent investigation, and a cardiovascular examination to ensure there are no vascular complications (e.g., radial-radial delay in aortic dissection). It is important to accurately assess the fluid status of the patient, as hypertension in the setting of fluid overload can respond well to diuretic therapy.

Investigations

Key investigations to consider include:

- ECG: assess for any signs of acute ischaemia or evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH)

- Urine dip: check for proteinuria, send formal urine ACR / PCR if positive

- Blood tests: assess renal function

Management and escalation

Hypertension >180/120 will always need medical treatment. In the absence of symptoms, oral medications should be given to lower blood pressure slowly. In most cases, aiming for a target of <160/100 over several hours is acceptable.

Excessive doses of antihypertensives should not be given to try and rapidly restore ‘normal’ blood pressure in asymptomatic patients, as this can lead to complications.

Remember to check for any contra-indications to the oral therapy chosen (e.g. avoid ACEIs in renal artery stenosis or acute kidney injury). In a patient who is naïve to anti-hypertensive therapy, amlodipine 5mg is generally a safe and effective first-line agent, and this can be reviewed in the morning by the treating medical team. Always discuss with a senior if you are unsure which agent to use.

In a hypertensive emergency (i.e. BP 180/120 with symptoms), escalate quickly to senior medical team members if an emergency call has not already been put out. These patients will need urgent blood pressure lowering therapy (e.g. GTN patch/infusion), as well as possible further investigations depending on symptoms (CT brain if severe headache or drowsiness, ECGs / troponins if chest pain).

Once initial management has begun, they are likely to need transfer to a high-dependency area for monitoring, and the critical care team should always be involved.

Hypotension

Common causes

- Hypovolemia (haemorrhage/dehydration)

- Vasodilation (sepsis/anaphylaxis/vasovagal response)

- Cardiogenic shock

- Medication-related (e.g. polypharmacy in the elderly, post-anaesthetic)

Triage

When triaging a patient with hypotension, it is important to determine whether this is an acute or chronic issue and whether there are any symptoms of end-organ hypoperfusion (e.g. confusion, syncope, chest pain, reduced urine output).

Certain patients have very low blood pressures at baseline or will be on medications that cause significant hypotension (e.g. Entresto in patients with CCF). If the patient has been hypotensive throughout their admission and is asymptomatic, this is likely to need less urgent review. Any new hypotension or associated symptoms is concerning and warrants early review.

It is also important to consider the rest of a patient’s observations. If the hypotension is associated with significant tachycardia, this is often a sign that the patient is haemodynamically compromised and will need urgent review.

Remember that some medications (such as beta-blockers) can limit a patient’s ability to mount a tachycardia response. If the hypotensive patient is febrile, this raises concerns about sepsis, and again, the patient should be seen more urgently.

Without a history of heart failure, it is generally safe to consider a bolus of intravenous fluid (e.g. 250/500ml STAT) before seeing the patient to see if this is associated with a clinical improvement in blood pressure. Even if the blood pressure comes up with a fluid challenge, it is still important to review the patient to diagnose and treat the underlying cause.

Assessment

Assess the patient for signs of compromise from the end of the bed. If the patient is sitting up looking well, they are less likely to be significantly compromised by the hypotension. In this case, there is likely time to quickly read the notes. A drowsy patient, looking unwell, complaining of pain or feeling unwell warrants an urgent ABCDE assessment.

The examination should focus on identifying the underlying cause of hypotension and assessing for complications.

A hypovolemic patient will often have dry mucous membranes, a non-visible JVP and be cool / shut down peripherally.

A vasodilated patient will often initially be warm peripherally, and there may be an associated fever in sepsis or associated urticarial rash in anaphylaxis.

A patient with cardiogenic shock will often have a history of heart failure or recent MI and will be cool and shut down peripherally with a raised JVP and signs of pulmonary oedema.

Investigations

Key investigations to consider include:

- ECG: assess for any signs of ischemia/arrhythmia

- VBG: should be considered in all hypotensive patients – a raised lactate indicates tissue ischemia. pH/lactate derangements are always significant and should be escalated to senior colleagues

- Blood tests: inflammatory markers to assess for signs of sepsis, urea & electrolytes / liver function tests to assess for end-organ dysfunction

Management and escalation

By the end of your assessment, it is important to have an idea of the cause of the hypotension and a plan to treat this pathology. If the cause is unclear, involving a senior is important.

Most vasodilatory/hypovolemic causes of hypotension should respond to intravenous fluid resuscitation in the first instance. If you are confident that the patient is not in cardiogenic shock, then initial IV fluid boluses can be trialled. If there is no response after significant fluid resuscitation (typically 2 litres), senior review and critical care advice should be sought – the patient may require vasopressor treatment.

If a patient is hypotensive with a suspected bleed (e.g. signs of UGI haemorrhage), the massive transfusion protocol (MTP) should be activated immediately to arrange urgent blood product availability. An emergency call should be put out in this situation, as many hands will be required to resuscitate the patient and make a plan to stop the bleeding (e.g., discussion with gastroenterology or the relevant surgical team).

A patient with suspected cardiogenic shock will always require urgent critical care review and input and should generally not be given intravenous fluid boluses, as this may worsen the clinical picture.

It is important to follow up patients after the initial review to ensure continued improvement. If a venous blood gas taken at the time of hypotension showed a raised lactate, but the hypotension has now resolved with treatment, the VBG should be repeated to ensure that the lactate is normalising and you are not missing another pathology.

If your shift is finishing, always hand these patients over for the oncoming team to review.

Fever

Common causes

- Infection/sepsis

- Pulmonary embolism

- Malignancy

- Post-operative fever

Triage

The key to triaging a patient with a fever is to determine whether the fever is new or ongoing in the presence of a known cause (most commonly infection) and to assess for any associated signs of sepsis.

Patients will often have mild tachypnoea or tachycardia associated with a fever. However, these can also be early signs of sepsis and thus warrant early review. Fever with associated hypotension is sepsis until proven otherwise and should be considered a medical emergency.

In a patient with a known source of infection (e.g., within the first 24 hours of admission for urosepsis) that has been started on appropriate antibiotics, fever can be an expected part of the illness. These patients may not need formal review in the absence of any signs of sepsis. However, it is always worth ensuring that a full septic screen and blood cultures have been sent within the last 24 hours and sending them if this is not the case.

All patients with a new fever will require an assessment to look for an infective source, although this can be triaged at a lower priority if there are no other derangements in observations. Before your review, it is worth asking the nursing staff to collect a urine sample for analysis and take blood cultures where possible.

Patients who have persistent fevers despite 24-48 hours of appropriate antibiotic therapy should be reviewed to ensure that there is no alternate cause for fever. Again this can be triaged at a lower priority in the absence of derangements in other observations or nursing concerns.

Assessment

The key to assessing a patient with fever is to look for a potential source of infection and ensure any sign of sepsis is identified and treated early.

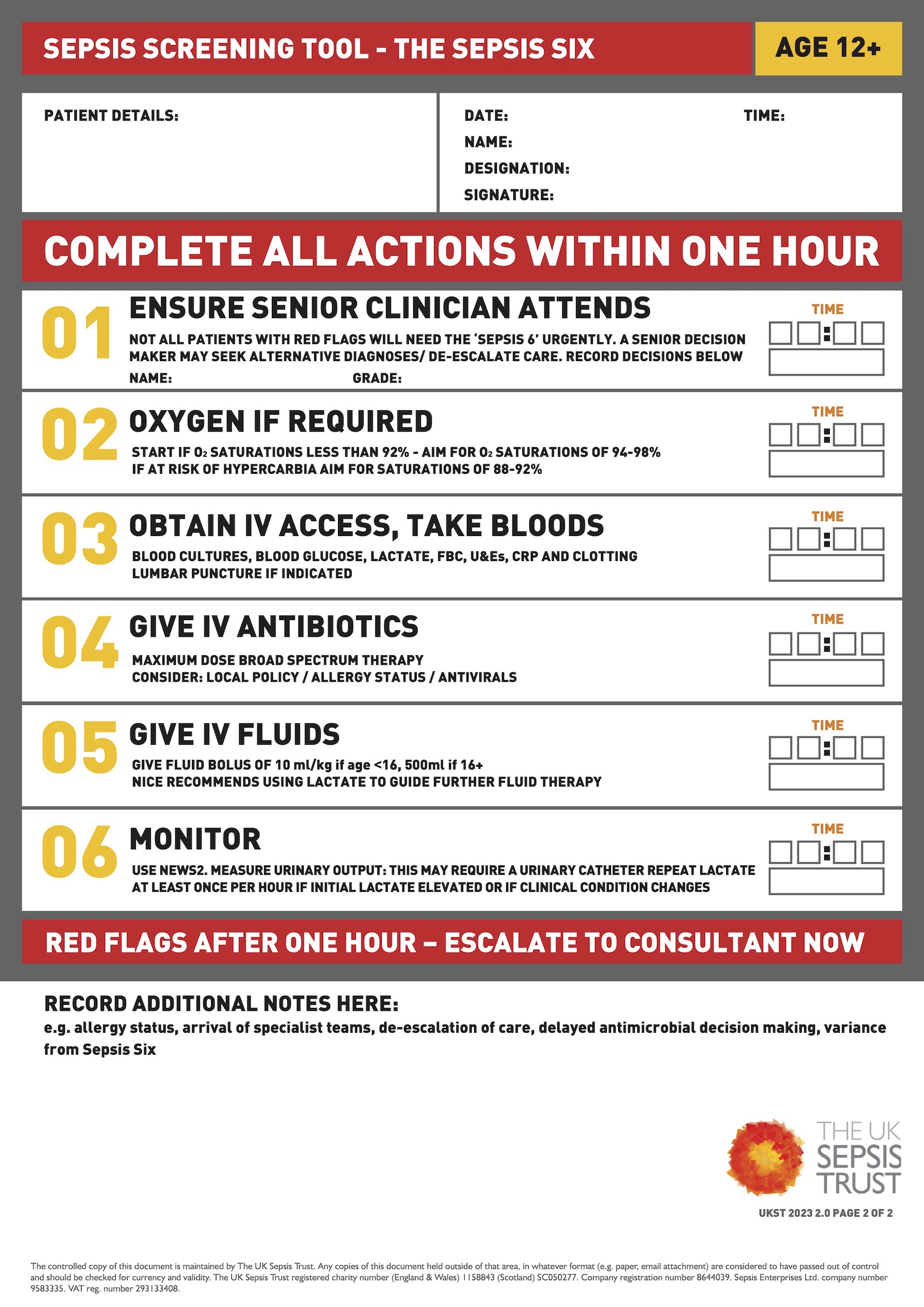

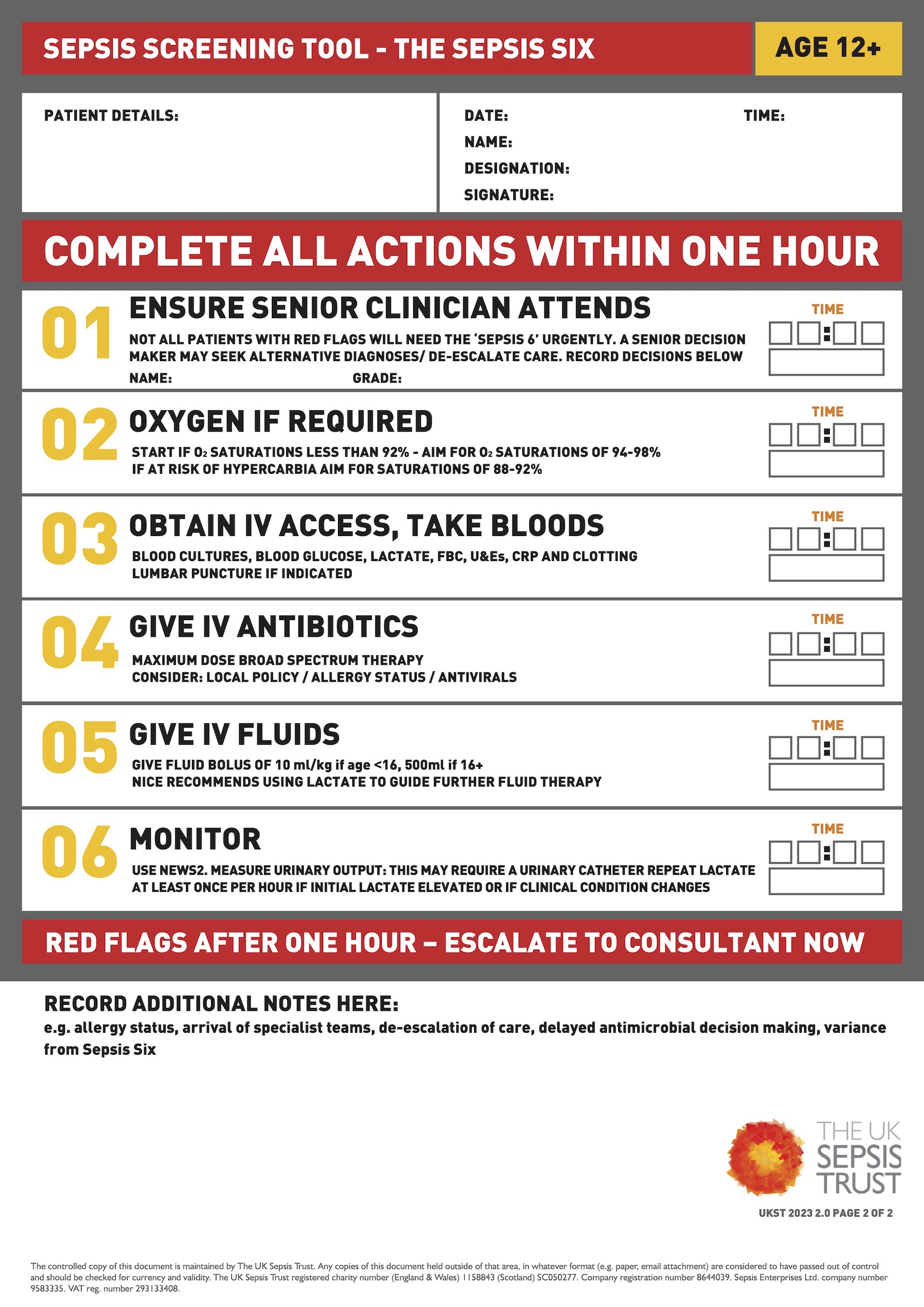

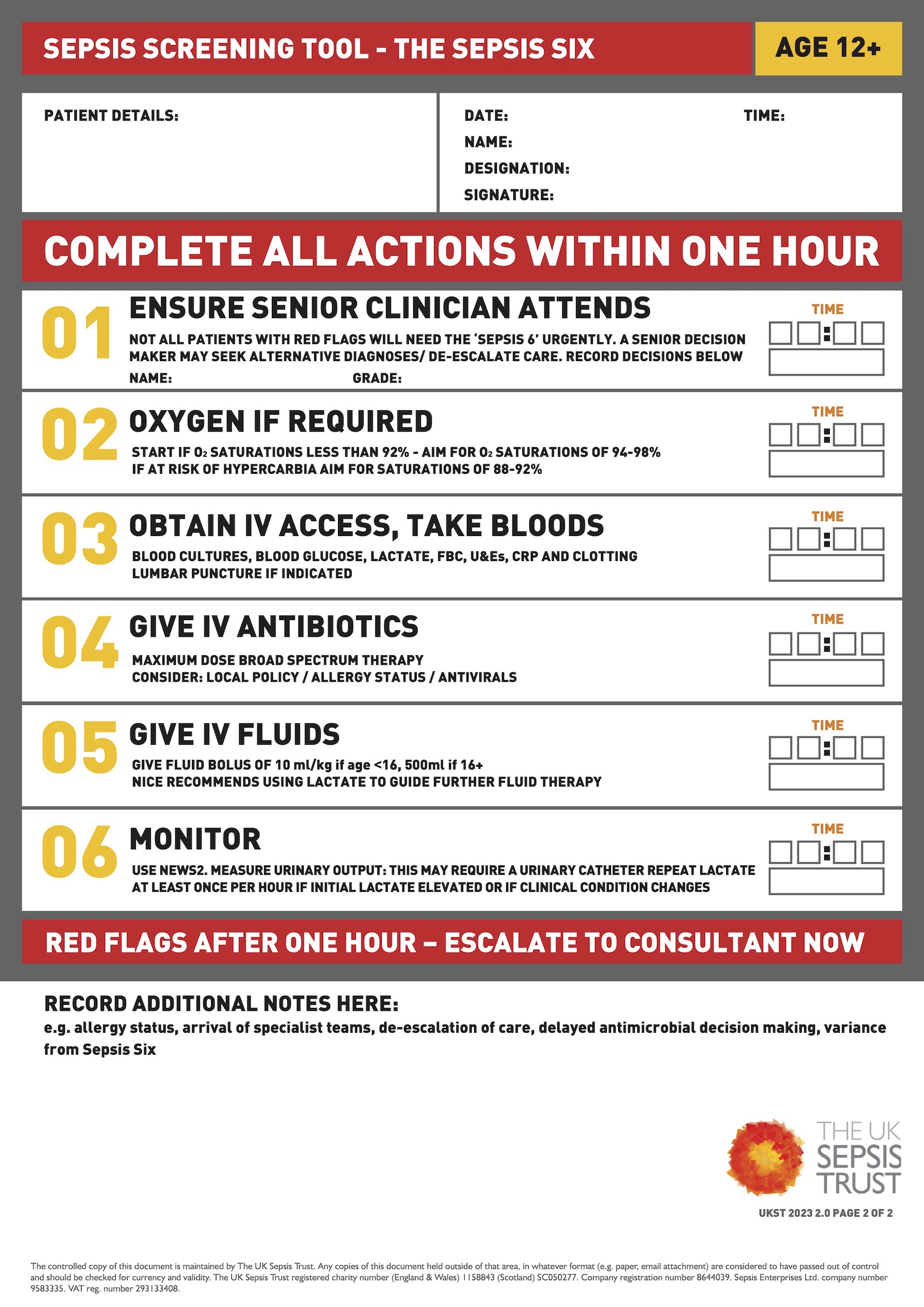

Always initially eyeball the patient from the end of the bed, as patients with significant sepsis will often look unwell. In this case, an A-E assessment (with an additional focus on finding a source of infection) will be required before starting early management (‘sepsis six’).

In the absence of signs of sepsis, patients’ notes will often give clues as to the source of the fever, particularly if this is not the first episode of fever during the admission. Look through recent bloods to assess inflammatory markers and pay close attention to recent microbiology. Patients often have blood or urine cultures sent on admission that may only recently have flagged positive.

On examination, careful auscultation of the chest is important, as well as a complete abdominal examination (chest and urinary sources of infection are most common). Also, look specifically at cannula sites / indwelling lines for signs of local infection. Ensure there is no photophobia or meningism that could suggest CNS infection (rare), and examine the skin for rashes or sites of skin/soft tissue infection (common).

Investigations

Key investigations to consider include:

- VBG: assess pH/lactate

- Blood tests: assess infection markers, look for complications of sepsis (AKI)

- Urine MCS: should be performed in all febrile patients

- Peripheral blood cultures: ensure these are performed in all febrile patients. If there are indwelling lines (e.g. PICC lines), one set should also be taken from the line to assess for line infection)

- Chest X-ray: should be performed in all febrile patients

- Viral swabs: should be performed in all febrile patients

Management and escalation

Patients with suspected sepsis should be identified quickly and treated according to the ‘sepsis six’ bundle. These patients will always require discussion with senior clinicians. If the source of infection is unclear, start broad-spectrum antibiotics according to local guidelines.

Once started on appropriate treatment, it is important to re-assess these patients later in your shift or hand them over to the oncoming team if your shift is due to end.

Key features to monitor are observations (look for improving tachycardia, tachypnoea), urine output (ensure >0.5ml/kg/hr) and lactate level (ensure down trending with treatment). Any septic patient with hypotension or a raised serum lactate despite fluid resuscitation should be urgently discussed with the critical care team.

If a patient continues to spike fevers despite 48 hours of appropriate antibiotic therapy, this can indicate that the therapy is not working and may need escalation. In the absence of any signs of sepsis, this decision can often be left to the patient’s own medical team. However, this decision should be escalated to a senior member of the on-call medical team.

In patients without a clear source of infection, it is important not to forget alternate diagnoses (PE, malignancy). In a well patient with no observation derangements suggesting sepsis, it is not always necessary to commence antibiotic therapy. However, it is vital to ensure that a full septic screen, including blood cultures and viral swabs has been sent.

Confusion / decreased GCS

Common causes

- Delirium

- Dementia

- Neurological disease (e.g. intracranial haemorrhage, stroke)

- CO2 retention

- Medication-induced (sedatives/opiates)

Triage

A confused/drowsy patient is a common problem. The majority of these will be caused by hospital-associated delirium. However, it is vital to consider other neurological diagnoses.

The key to triage is an accurate neurological assessment by an experienced nurse. Ask the nurses to perform a full set of neurological observations (“neuro obs”), including GCS, pupil assessment and limb strength, as this can provide valuable information for triage, and regular neuro-obs can keep the patient safe whilst awaiting your review.

A GCS of 14 (E4V4M6, i.e. a confused patient) will be the most common patient you will be asked to review. Any GCS below 14 generally warrants urgent review, as well as any patient with other abnormalities on a set of neuro-obs, (e.g. focal limb weakness or unequal pupils).

When triaging a confused patient, it is important to understand if this is new or old.

Many patients with dementia will be permanently confused, especially overnight. Ask if the ward staff have looked after the patient before and whether this behaviour is new for them? Patients with chronic confusion overnight can be triaged as low-priority for review unless the nursing staff are concerned that this is worsening.

Patients with new confusion but no other concerning features should be reviewed when time allows, to identify and treat the underlying cause.

Assessment

If the patient is comfortable, take some time to look through the notes, as there will often be clues about the potential cause of delirium. A history of dementia or previous episodes of delirium increases the risk of further delirium.

Review the medication chart thoroughly for any medications that may cause delirium (particularly opiate medications), and look at the bowel chart to rule out constipation as a cause.

Review recent blood results and microbiology to see if there are any potential causes (e.g. electrolyte disturbances, positive urine culture).

Examine the patient thoroughly from top to toe. Special attention should be taken to identify causes of delirium (infection, constipation etc), and a thorough neurological examination should be undertaken to look for signs of alternate central nervous system pathology (e.g. focal arm or leg weakness, unequal pupils, facial droop).

ACVPU vs AVPU

AVPU was the original method of rapidly assessing level of consciousness, and this scale is still commonly referred to. With the development of NEWS2, new-onset confusion (‘C‘) was added to the score to make ACVPU.

Patients who develop new or worsening confusion (e.g. delirium) are at risk of deterioration. Therefore, identifying and implementing appropriate treatment for these patients is important.

Investigations

Key investigations to consider include:

- Capillary blood glucose: should be performed in all acutely confused patients

- Urine MCS: in a patient without a clear cause for confusion, always check the urine

- ECG: rule out cardiac events precipitating confusion

- Chest X-ray: always perform in a patient without a clear cause for confusion

- Blood tests: check electrolytes, inflammatory markers

- VBG: check CO2 / lactate

- CT brain: should be considered in all patients without a clear cause of confusion. If any features are consistent with stroke, urgently discuss with senior colleagues to consider the need for acute stroke imaging.

Management and escalation

The key to managing these patients is to find and treat an underlying cause and remove factors that may perpetuate an ongoing delirium.

The first important step is to rule out significant neurological diseases, such as stroke / ICH. If there is a rapidly dropping GCS or any localising neurological signs on examination, an urgent CT head is always necessary, and these patients should be escalated to a senior on-call (if suspecting stroke, a stroke-call may need to be put out and specific neuro-imaging ordered). In most cases, an emergency call will be warranted.

Outside of these cases, deciding who to send for neuro-imaging can be tricky, and it is always worth involving a senior colleague if uncertain. Without a quickly falling GCS or localising pathology, it will usually be safe to carry out your full assessment to see if there are any other clear causes of confusion (e.g. UTI) before rushing to neuro-imaging.

In some patients, a cause for delirium/confusion is not always found. In these cases, it is important to monitor and try to prevent complications (e.g. falls, aspiration) as well as withholding common medications that may be a culprit (e.g. narcotics).

Make a clear plan to monitor bowels and oral intake, and await the results of your investigations / septic screen. Any imaging or investigations you have ordered should always be handed over to the oncoming team if you cannot chase them yourself so that they can be acted upon if abnormal.

References

- Figure 1-7; Figure 9. Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Updated report of a working party. London: RCP, 2017.

- Figure 8. The UK Sepsis Trust. Sepsis six screening tool.