- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

A 50-year-old man presents to his GP with back pain. Work through the case to reach a diagnosis.

UK Medical Licensing Assessment (UKMLA)

This clinical case maps to the following UKMLA presentations:

History

Presenting complaint

“This morning I was lifting a TV out of my car when I suddenly developed really awful back pain. It’s been there ever since and I’m struggling to deal with it.”

History of presenting complaint

Where is the back pain?

“In my lower back”

Did anything happen to trigger the pain? Did it come on suddenly or gradually?

“The back pain started as soon as I lifted a heavy package this morning and I felt a click.”

What kind of pain is this? (e.g. sharp, aching, burning) Is it continuous or intermittent?

“There is a constant ache and then sharp pain whenever I try to bend.”

Does the pain move anywhere else?

“No, not that I’ve noticed”

Are there any other symptoms that seem associated (e.g. weakness, numbness, saddle anaesthesia, urinary or faecal incontinence, weight loss, fevers, sweats)?

“I don’t have any weakness or numbness and I’ve opened my bowels today without any issues, I’m also passing water fine. I haven’t noticed any weight loss, fevers, or sweats.”

Does anything make it better or worse? Is it worse when you walk, sit down, or lay flat?

“Paracetamol, ibuprofen, and a heat pack have helped a little bit, but not much. The pain is definitely worse when I bend, lying still seems to help a little bit.”

On a scale of 1-10, how bad is the pain?

“The pain is about 8 out of 10 at its worst”

Have you experienced back pain in the past? Was it similar to what you are currently experiencing?

“I’ve had the usual joint aches here and there but nothing this bad ever.”

Other areas of the history

Past medical and surgical history

- Musculoskeletal conditions

- Rheumatological conditions

- Malignancy

- Previous trauma

- Other medical conditions

- Previous spinal surgery

“I have high blood pressure but otherwise I’m fit and well as far as I know.”

Medication history/allergies

- Does he take any regular medication?

- Does he have any allergies?

“I just take lisinopril for my blood pressure. No allergies that I know of.”

Family history

- Do any medical problems run in the family?

“Nope.”

Social history

- Accommodation (e.g. house, flat, bungalow)

- Home situation (e.g. others living with the patient)

- Level of functional independence

- Current occupation

- Smoking status

- Alcohol history

- Recreational drug use

“I live with my wife in a flat and neither of us smokes or drinks. I work as a delivery driver and I’m fully independent.”

Systems review

- Weight loss

- Appetite

- Fevers

- Fatigue

- Haematuria

- Nausea and vomiting

“I’ve been fairly tired recently, but just assumed that was because of work.”

Red flags in back pain are features in the history that may suggest a serious cause of pain, such as cancer, spinal fracture or cauda equina:

- Back pain in those younger than 20 or older than 50

- Non-mechanical pain

- Thoracic pain

- Saddle anaesthesia

- Bladder dysfunction (e.g. urinary retention, incontinence)

- Faecal incontinence

- Limb weakness

- Associated trauma

- Weight loss

- Fever

- Structural abnormality of the spine

Clinical examination

If there were any history or examination findings suggestive of cauda equina syndrome, you would also need to perform:

- Rectal examination – to assess peri-anal sensation and sphincter competence

If there were any history or examination findings suggestive of intra-abdominal pathology, you would also need to perform:

- Basic observations (vital signs): to assess haemodynamic stability

- Abdominal examination: to assess for any signs suggestive of abdominal pathology

Examination findings:

- Gait: the patient is walking slightly ‘stooped’ due to the pain

- Palpation: there is point tenderness in the lower lumbar spine

- Movement: there is limited range of spinal movement due to pain

- Power: MRC grade 5/5 in both lower limbs

- Sensation: normal sensation in all modalities

- Reflexes: normal

- General inspection: some mild conjunctival pallor

- Rectal examination: not performed

Investigations

- FBC: raised WCC may suggest an infective cause, iron deficiency anaemia may suggest malignancy)

- U&Es: taking NSAIDs and an ACE inhibitor, therefore at risk of acute kidney injury)

- LFTs: ALP elevation may point towards skeletal disease – e.g. bony metastases)

- Bone profile: hypercalcaemia – e.g. bony metastases)

- CRP: raised CRP – e.g. discitis, ankylosing spondylitis)

- ESR: raised ESR – e.g. ankylosing spondylitis)

- Urinalysis

Investigation results

The results of the patient’s initial investigations are shown below:

- Hb 105 g/L

- WCC 8.5 x 109/L

- Neutrophils 5.7 x 109/L

- Lymphocytes 1.9 x 109/L

- Platelets 190 x 109/L

- Na+ 137 mmol/L

- K+ 4.9 mmol/l

- Creatinine 150 μmol/L

- Urea 8.7 mmol/L

- ALP 250 IU/L

- ALT normal

- GGT normal

- Bilirubin 12 μmol/L

- Calcium (adjusted) 3.43 mmol/L

- Phosphate 0.8 mmol/L

CRP 12

ESR raised

Urinalysis normal

- Parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels

- Thyroid function tests (TFTs)

- Serum protein electrophoresis

- Urine protein electrophoresis (Bence Jones proteins)

- Measurement of immunoglobulins

- Vitamin D levels

- HIV screen

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme levels (sarcoidosis)

Not all of these investigations are warranted immediately (e.g. HIV/ACE) and the choice of investigations should be informed by clinical suspicion.

Further investigations

The results of the additional investigations are shown below:

- PTH: 0.5 pmol/L (1.05 – 6.83 pmol/L)

- IgG: 59 g/L (5.9 – 15.6 g/L)

- IgA: 0.5 g/L (0.6 – 5 g/L)

- IgM: 0.3 g/L (0.4 – 2.3 g/L)

- Serum electrophoresis: a band in the gamma region is noted

- Immunofixation: IgG kappa paraprotein is detected, totalling 52 g/L

Imaging

The patient’s lumbar X-Ray is shown below:

- Loss of height of the L4 vertebrae (particularly anteriorly)

- Appearances consistent with a wedge fracture of the lumbar spine

Diagnosis

- Primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy with bony metastases

- Multiple myeloma

- Sarcoidosis

The most likely diagnosis is multiple myeloma.

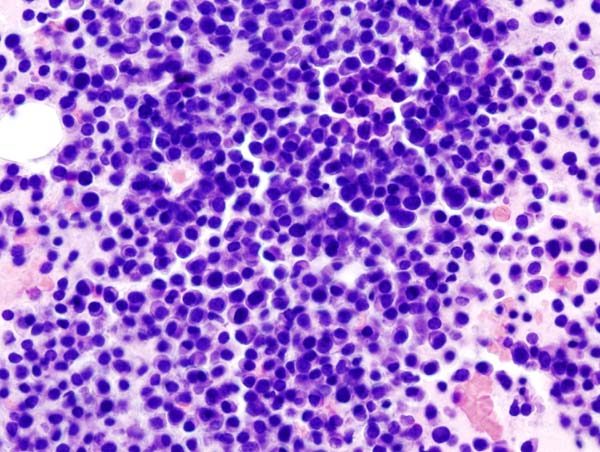

Multiple myeloma involves the clonal proliferation of plasma cells. An initiating event occurs that gives a specific plasma cell a survival advantage (e.g. chromosomal translocation). As a result, normal mechanisms to reduce proliferation are overcome and the plasma cell clone begins to proliferate.

CRAB is a useful mnemonic to help remember the most common features of myeloma:

- HyperCalcaemia: cytokines result in osteoclast dysregulation

- Renal failure: light chains clog up the renal tubules

- Anaemia: the bone marrow becomes overcrowded with plasma cells

- Bone lesions: cytokines result in osteoclast dysregulation

Symptomatic myeloma criteria

The below criteria must be met for a diagnosis of symptomatic myeloma3:

-

Clonal plasma cells >10% on bone marrow biopsy or in a biopsy from other tissues.

-

A monoclonal protein (paraprotein) in either serum or urine (unless non-secretory, in which case there need to be >30% clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow).

-

Evidence of end-organ damage felt related to the plasma cell disorder (e.g. CRAB).

Asymptomatic myeloma

This type of myeloma is often referred to as smouldering myeloma. It differs from symptomatic myeloma because of the absence of end-organ damage.

The below criteria must be met for a diagnosis of asymptomatic myeloma3:

- Serum M paraprotein (IgG or IgA) >30 g/L or urinary M protein ≥500 mg per 24 hours and/or clonal bone marrow plasma cells 10-60%.

- No myeloma-related organ or tissue impairment, or amyloidosis.

Management

This patient should be admitted to the hospital for treatment of their hypercalcaemia, as his calcium is significantly raised. Treatment of hypercalcaemia involves:

Intravenous fluids

- NaCl (0.9%) can be used to rehydrate the patient and encourage urinary excretion of calcium.

- Fluid balance should be closely monitored to avoid overloading the patient.

Bisphosphonates

- Bisphosphonates (e.g. Pamidronate) reduce bone turnover and can be used for short-term treatment of hypercalcaemia, once patients have been rehydrated.

- Pamidronate also has an analgesic effect on vertebral fractures.

Myeloma is currently an incurable disease that is chronic, relapsing and remitting. Treatment is aimed at controlling the disease, prolonging survival and maximising quality of life.

Initial treatment

This man has symptomatic myeloma and therefore requires active treatment4.

Treatment choice is based on the age and fitness level of the patient.

Younger patients (< 65 years or < 70 years and in a good clinical condition):

- Induction chemotherapy (bortezomib & dexamethasone) followed by high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is the standard treatment.

- This would be the most appropriate choice for the patient in this scenario.

Maintenance

Lenalidomide has been approved as monotherapy for the maintenance treatment of younger adult patients with newly diagnosed myeloma who have undergone autologous stem cell transplantation. Maintenance therapy is not recommended for elderly patients.

Patients who have undergone myeloma treatment (and those with smouldering myeloma) should be reviewed at least every 3 months, including assessment of the following:

- Myeloma symptoms and treatment side effects (e.g. fatigue, bony pain)

- FBC, renal function, bone profile, serum immunoglobulins and serum protein electrophoresis

Prognosis/Complications

Neutropenic sepsis: patients develop neutropenia as part of the pre-conditioning process prior to transplantation. As a result, patients remain highly susceptible to developing infections during the acute transplantation period.

Graft failure: occurs when the stem cells fail to settle in the bone marrow and begin to make new cells. Patients are then unable to make new blood cells and therefore develop pancytopenia.

- Pathological fractures (as in this scenario) due to lytic bony lesions

- Spinal cord compression secondary to vertebral body fracture

- Recurrent infections due to impaired immunity (e.g. hypogammaglobulinaemia)

The prognosis remains variable, with median survival estimated to be 4.5 years. Some patients will live for more than eight years after diagnosis, whereas high-risk disease usually causes death within 24 months.

Specific genetic lesions are associated with worse outcomes (e.g. IgH translocations involving chromosomes 4 and 16 and/or deletion of the short arm of chromosome 17)

Reviewers

TeamHaem

Editor

Dr Jess Speller

References

- James Heilman, MD. Lumbar spine fracture. Licence: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK].

- KGH. Bone marrow image. Licence [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK].

- Patient.info. Multiple myeloma. Updated May 2018. Available from: [LINK].

- Multiple myeloma: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up; ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline (2017). Available from: [LINK].