- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

This article is intended to provide healthcare students with an overview of jaundice, which includes potential causes (pre-hepatic, hepatic and post-hepatic), examination findings, investigations and management strategies.

What is jaundice?

Jaundice is the name given when excess bilirubin (typically greater than 35 µmol/L) accumulates and becomes visible as a yellow discolouration of the sclera and/or skin dependent on skin pigmentation.1

Jaundice can be a symptom of a wide range of diseases. Understanding the mechanism of bilirubin metabolism can help identify the underlying disease process.

Pathophysiology

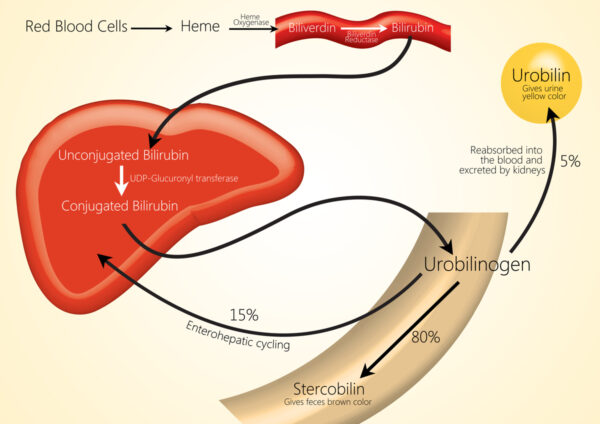

Bilirubin is a yellow pigment produced when the reticuloendothelial system breaks down red blood cells in a process known as haemolysis.

Macrophages (reticuloendothelial cells) break down haemoglobin into haem and globin. Then, haem is further broken down into iron (which is recycled) and biliverdin by haem oxygenase. Biliverdin is then broken down further into bilirubin.

Bilirubin is not water-soluble, so it relies on a transport protein (albumin) to be transported to the liver in the bloodstream.

Once in the liver, glucuronic acid is added to the unconjugated bilirubin by glucuronyl transferase to form conjugated bilirubin, which is water soluble and can be excreted into the duodenum.

Once the conjugated bilirubin reaches the colon, it is then deconjugated by colonic bacteria to form urobilinogen. The majority (80%) of urobilogen is oxidised by intestinal bacteria to create stercobilin, which is excreted via faeces and gives them their brown colour.

The remaining 20% is reabsorbed into the bloodstream and transported to the liver, where some is used for bile production. The remainder is carried to the kidneys, oxidised into urobilin and excreted in urine (which gives urine its yellow colour).

Understanding bilirubin metabolism is crucial in understanding the different disease processes that can cause jaundice, as it will affect investigation and management strategies.

Causes of jaundice

Jaundice can be broadly divided into:

- Pre-hepatic jaundice

- Intrahepatic jaundice

- Post-hepatic jaundice

Table 1. Summary of conditions which cause jaundice.

| Classification | Conditions |

|

Pre-hepatic jaundice |

|

|

Intrahepatic jaundice |

|

|

Extrahepatic jaundice |

|

Pre-hepatic jaundice

Pre-hepatic jaundice occurs when bilirubin metabolism has been affected before bilirubin reaches the liver (i.e., unconjugated bilirubin).

Generally, this type of jaundice is caused by issues relating to red cell breakdown, where increased haemolysis results in excess bilirubin.

As bilirubin is unconjugated at this stage, this is called unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia.

Haemolytic anaemias (i.e. spherocytosis)

Increased haemolytic activity increases bilirubin. Haemolysis can occur intravascularly (less common) or extravascularly (where phagocytes remove red cells due to red cell defects or immunoglobulins bound to their surface).2

Disorders resulting in increased haemolysis can be genetic or acquired.

Genetic causes

Genetic causes include red cell membrane abnormalities (in the case of hereditary spherocytosis), abnormalities of haemoglobin (sickle cell anaemia, thalassaemias) or enzyme defects (G6PD deficiency, pyruvate kinase deficiency).

Acquired causes

Acquired haemolytic anaemias tend to be immune-mediated and can either be isoimmune (e.g. a blood transfusion reaction) or autoimmune (SLE, haematological abnormalities such as lymphoma or leukaemia, or may be drug-related).

Non-immune causes do occur but tend to be associated with poorer outcomes. Examples include disseminated intravascular coagulation, haemolytic uraemic syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenia, hypersplenism and cirrhosis.

Patients who experience excessive intravascular haemolysis may also experience haemoglobinuria (presence of haemoglobin in the urine), resulting in the patient reporting red or amber-coloured urine.

Gilbert’s syndrome

Gilbert’s syndrome is a benign genetic condition in which bilirubin is not transported into bile at the usual rate, resulting in an accumulation in the bloodstream and resultant jaundice.3

The presence of jaundice is intermittent and can be precipitated by several factors, including stress, current infection, sleep deprivation and menstruation. Gilbert’s syndrome does not usually require treatment, as the disease does not progress or cause any organ damage (such as chronic liver disease).

Crigler-Najjar syndrome

Crigler-Najjar syndrome is a very rare autosomal recessive inherited disorder where deficiency of diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase results in the impairment of the ability to conjugate and excrete bilirubin. This is seen in neonates.

Unlike Gilbert syndrome, Crigler-Najjar type 1 can be life-threatening due to neurological damage from bilirubin encephalopathy. A liver transplant is the only option to cure this disease.

Intrahepatic (hepatocellular or intrahepatic cholestasis)

Intrahepatic jaundice occurs when hepatocyte damage results in reduced bilirubin conjugation or structural abnormalities that cause cholestasis.

Hepatocytes can be damaged by viruses, alcohol, autoimmune processes or drugs and can result in permanent scarring, which, if left untreated, can progress to cirrhosis.

Viral hepatitis

Viral hepatitis (inflammation of the liver) is caused by a group of hepatitis viruses labelled from A-E, which can result in both short and long-term hepatocellular damage.

These viruses are variable in prevalence around the globe and have different routes of transmission:

- Hepatitis A and E are transmitted via contaminated food and water (faeco-oral route)

- Hepatitis B and C are blood-borne viruses (spread by contaminated bodily fluids such as blood or semen)

- Hepatitis D can only be contracted if a person is already infected with hepatitis B.

Most viral hepatitis follows a similar clinical course with three distinct phases: prodromal, icteric and convalescent.4

The prodromal phase includes non-specific flu-like and gastrointestinal symptoms (such as nausea, vomiting, right upper quadrant pain) but no specific signs on examination.

During the icteric phase, patients will experience jaundice (and pale stools/dark urine if there is cholestasis), pruritis, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, with symptoms improving once jaundice occurs. There may be hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy and hepatic tenderness on examination.

The final phase (convalescent) will usually present with malaise and hepatic tenderness.

The prognosis for viral hepatitis’ is variable. For example, hepatitis A and E tend to be self-limiting and do not cause chronic liver disease. Conversely, hepatitis B and C will progress to chronic liver disease (i.e. cirrhosis) if left untreated, which can ultimately be fatal.

Alcoholic hepatitis

As the name suggests, this is hepatitis caused by the use of excess alcohol.

The liver metabolises alcohol and produces acetaldehyde as a by-product, which subsequently binds to proteins within liver cells, causing hepatocyte injury. Alcoholic hepatitis is usually treated supportively, although in some cases, steroids can be used to improve prognosis.

Autoimmune hepatitis

As the name suggests, this is a condition where autoimmune processes result in damage to hepatocytes. The clinical presentation is variable, ranging from asymptomatic to fulminant liver failure, although unfortunately, by the time patients have become symptomatic, cirrhosis is usually present.

Symptoms include jaundice, weight loss, nausea, upper abdominal discomfort, fatigue, oedema and arthralgias. On examination, hepatomegaly, jaundice, splenomegaly and ascites are common.

Drug-induced hepatitis

Hepatocytes can become damaged due to medications, which may be related to the dose prescribed or the medication itself. Common culprits include antimicrobials (such as nitrofurantoin and co-amoxiclav), paracetamol, methotrexate, carbimazole, anabolic steroids, azathioprine and oestrogens.

There is not a singular specific treatment beyond stopping the medication that is causing the problem. Whilst some medications may have an antidote (such as N-acetylcysteine for paracetamol), treatment may not be successful, and subsequent hepatic damage may be permanent.

In the case of liver failure due to a drug-induced liver injury, a liver transplant may be considered. However, trict criteria must be met (such as the King’s College Criteria for paracetamol toxicity).

Decompensated cirrhosis

Perhaps one of the most common presentations of jaundice is decompensated cirrhosis.

Cirrhosis is widespread irreversible scarring of hepatic tissue, resulting in abnormal nodules. Evidence of liver failure only becomes apparent once 80-90% of hepatic tissue has been affected by cirrhosis.5

Intrahepatic vasculature becomes distorted by fibrosis of hepatic tissue, resulting in increased intrahepatic resistance and subsequent portal hypertension.

Portal hypertension, in turn, can lead to the formation of oesophageal varices, fluid retention and decreased renal perfusion.

Cirrhosis can occur due to a variety of reasons. However, excess alcohol use and hepatitis B and C are the most common causes worldwide.

Patients with cirrhosis can be stable for long periods but can decompensate after a trigger event, which could be an infection (i.e. spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), bleeding (such as a variceal bleed), alcohol binge, or in some cases, decompensation will have no identified cause.

Intrahepatic cholestasis

Intrahepatic jaundice may also occur due to intrahepatic cholestasis.

One potential cause of intrahepatic cholestasis is primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), a slowly progressive autoimmune disease which destroys small interlobular bile ducts.

Intrahepatic cholestasis then causes damage to hepatocytes, resulting in fibrosis, which may then progress to cirrhosis. PBC is associated with multiple other autoimmune diseases, including systemic sclerosis and thyroid disease.

Another cause of intrahepatic jaundice is Dubin-Johnson syndrome, which is a rare benign disorder in which there is excess conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia due to impaired secretion of conjugated bilirubin and the presence of abnormal pigment within hepatic parenchymal cells.6 Unlike PBC, this condition cannot progress to cirrhosis due to the excretion of bilirubin glucuronides, resulting in a milder form of conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia.

Extrahepatic jaundice

Extrahepatic jaundice generally occurs when there is extrahepatic cholestasis, which often occurs due to distortion of the biliary tree due to intraluminal structural abnormalities (such as strictures) or extrinsic compression.

Common bile duct stone

Gallstones in the common bile duct are one of the most common causes of extrahepatic cholestasis. This occurs when a gallstone leaves the gallbladder but becomes lodged within the common bile duct. Cholestasis then occurs due to obstruction of biliary drainage by gallstone.

Treatment usually involves endoscopic retrocholangiopancreatography (ERCP), where the stone can be removed via endoscopic methods. Occasionally, this will be unsuccessful and rely on open surgical management.

Cholangitis

Cholangitis is an acute infection of the biliary tree. Typically, symptoms include Charcot’s triad of fever, jaundice and right upper quadrant pain. Prompt treatment with antibiotics is required to treat this condition.

Bile duct strictures

Inflammation within the walls of the bile duct can cause strictures, which then narrow the intraluminal space and prevent the adequate anterograde flow of bile.

These can occur for several reasons, including recurrent insults such as biliary stones or pancreatitis, or can occur due to an autoimmune condition such as primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Management of the stricture will depend on the underlying cause, but the management principle is to improve the bile flow through the biliary tree.

Malignancy (head of pancreas, cholangiocarcinoma)

Bile ducts can be obstructed due to malignancy either inside the common bile duct or gallbladder or due to malignancy outside of the biliary tree, which causes extrinsic compression.

Cholangiocarcinoma is a cancer of the gallbladder and bile duct, which sadly often presents in the more advanced stages of the disease with jaundice, upper quadrant pain and weight loss. Jaundice occurs due to intraluminal obstruction of anterograde bile flow. Unfortunately, often, by the time symptoms become apparent, malignancy has already spread, and treatment will be palliative.

Conversely, cancer of the head of the pancreas can cause cholestasis through extrinsic compression of the biliary tree. Again, symptoms tend to be present late in the disease process, with key symptoms being jaundice, weight loss and abdominal pain.

If malignancy is discovered at the point where the disease is still localised to the pancreas, then curative treatment in the form of pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) with neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be considered. However, again, unfortunately, treatment is largely palliative due to advanced disease at presentation.

Pancreatitis

Inflammation of the pancreas, or pancreatitis, results in the release of exocrine enzymes, which then destroy pancreatic tissue.

The most common causes for this are gallstone disease and excess alcohol consumption, and typically, patients will present with severe epigastric pain and vomiting.

Jaundice can occur for several reasons when pancreatitis is present: this may be due to a common bile duct stone, excess alcohol use, or extrinsic compression of the common bile duct due to an increase in the size of the pancreas due to severe inflammation.

Treatment is primarily supportive. However, pancreatitis is a serious condition that may require intensive care treatment.

Assessment of the patient with jaundice

Clinical features

As discussed, there is a wide range of underlying causes of jaundice. Some causes will be associated with specific clinical signs or symptoms:

- Fever: suggested an infective cause (e.g. cholangitis, viral hepatitis)

- Pallor/pale conjunctivae: haemolytic anaemias

- Weight loss: malignancies such as head of pancreas cancer and cholangiocarcinoma

- Gynaecomastia: excess fatty breast tissue in male patients as a result of oestrogen and testosterone imbalance

- Caput medusa: portal hypertension occurs as a result of cirrhosis. Due to this, collateral blood vessels form and enlarge, including peri-umbilical vessels, which form the ‘head of Medusa’ around the umbilicus

- Liver flap: this occurs primarily in decompensated cirrhosis, where excess ammonia results in asterixis

- Ascites: this is excess fluid accumulation in the abdomen and occurs in multiple conditions (including intra-abdominal malignancies) but occurs in advanced liver disease due to fluid retention

- Spider naevi (aka spider telangiectasia): small red lesions with a central spot and outward reaching lines (much like a spider’s web). Pressing the lesion will result in temporary obliteration of the lesion, which will then be refilled when pressure is removed. These occur due to excess oestrogen

- Splenomegaly: this occurs as a late stage of cirrhosis due to portal hypertension. Increased resistance of blood through vessels in the liver results in a backflow and splenomegaly as a result

- Peripheral oedema: usually seen as swelling of the lower legs, this occurs as a result of fluid retention that occurs as a side effect of cirrhosis.

Laboratory investigations

In suspected pre-hepatic jaundice and haemolytic anaemia, relevant blood tests include:

- Haptoglobin: a protein which attaches to haemoglobin; decreased when there is an increase in red cell breakdown, usually low or non-detectable in haemolytic anaemia

- Lactase dehydrogenase (LDH): released when cells are destroyed, so increased in haemolytic anaemia due to increased cell turnover

- Blood film: as jaundice can be caused by haemolytic anaemia secondary to haematological malignancy, a blood film can help identify abnormalities consistent with cancer.

Split bilirubin

A “split bilirubin” is useful to check whether jaundice is pre-hepatic or intrahepatic/posthepatic. To do this, you simultaneously check conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin. If the problem is pre-hepatic, then the unconjugated bilirubin will be higher.

In cases of hepatocellular jaundice, liver function tests (LFTs) will be most helpful and indicate hepatocyte damage.

AST and ALT are transaminases (enzymes) found in liver cells, which means there will be raised serum levels if there is any evidence of liver injury.

The AST:ALT ratio can help to determine the mechanism of hepatocellular injury: a ratio of more than 2:1 is indicative of alcoholic liver disease. Likewise, an isolated GGT rise is a sign of excess alcohol use.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to interpreting liver function tests (LFTs).

Viral hepatitis screen

As viral hepatitis is a cause of jaundice, these are typically screened for.

Table 1. Basic viral hepatitis screen.

| Blood test | What it suggests |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Current hepatitis B infection |

| Hepatitis B core antibodies | Previous hepatotos B infection |

| Hepatitis C antibodies | Previous hepatitis C infection |

Additionally, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and HIV should be tested as potential causes of viral hepatitis.

Further blood tests

Further blood tests are usually sent as part of a non-invasive liver screen to exclude other causes of jaundice.

Table 2. Additional biochemistry investigations for jaundice.

| Blood test | What it suggests |

| Caeruloplasmin | Raised levels are seen in Wilson’s disease, a disease of copper metabolism |

| Ferritin and iron studies | Raised levels are suggestive of haemochromatosis, a disease of iron metabolism |

| HbA1c | Poorly controlled diabetes is associated with liver disease |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin | Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is a rare and inherited cause of liver cirrhosis |

Table 3. Immunoglobulins

| Blood test | What it suggests |

| IgG | Forms the majority of circulating immunoglobulins and is involved in the secondary immune response. Associated with autoimmune hepatitis. |

| IgM | Forms around 10% of circulating immunoglobulins and is involved in the primary immune response. Associated with primary biliary cirrhosis.7 |

| IgA | Involved in protecting mucous membranes, forms around 15% of total immunoglobulins. |

Autoantibodies will be tested for if autoimmune hepatitis is suspected as the cause of jaundice.

Table 4. Common autoantibodies that may be tested for as part of a non-invasive liver screen.

| Blood test | Associated conditions |

| Antinuclear antibody (ANA) | Autoimmune hepatitis, SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, Sjorgren’s disease, Addison’s disease |

| Smooth muscle antibody | Autoimmune hepatitis |

| Liver kidney microsomal antibody (anti-LKM) | Differentiates between type 1 and type 2 autoimmune hepatitis (AIH): associated with type 2 AIH |

| Anti-mitochondrial antibodies | Associated with primary biliary cirrhosis |

Ascitic fluid analysis

If a patient presents with jaundice and ascites, a sample of ascitic fluid may be sent to confirm or rule out specific diagnoses.

Ascitic fluid is collected during an ascitic aspiration (ascitic tap) and can be sent for microscopy, culture and sensitivities (M, C &S). Gram staining is used to identify any organisms initially and count numbers of white cells.

If the white cell count of the ascitic fluid is >250/µL, this indicates spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). SBP is a spontaneous bacterial infection of fluid in the peritoneum. If the white cell count is predominantly polymorphs, this confirms that bacteria is the likely cause. If the white cell count is >250/ µL and predominantly lymphocytes, this may indicate tuberculosis.

Imaging

Ultrasound

Abdominal ultrasound is a minimally invasive imaging method that can assess the liver and gallbladder for pathology. Ultrasound can detect pathologies such as steatosis, fibrosis, some nodules, cholecystitis and gallstone disease.

Computed tomography (CT)

This is likely to be used in the case of suspected malignancy, where more detailed imaging over a larger area than can be achieved via ultrasound is required. However, the nephrotoxic impact of contrast and radiation burden must be considered.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) can be used to assess disease of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system.

This is often used in cases where pathology of the biliary tree is suspected but not visible on other imaging such as ultrasound or computed tomography, such as gallstones, or for patients where endoscopy is considered too high risk. Possible contraindications to an MRCP include certain pacemakers or metal replacement body parts.

Endoscopy

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a diagnostic and interventional procedure generally carried out by gastroenterologists, which uses endoscopy and fluoroscopy to visualise the pancreaticobiliary ductal system.3

An endoscope is passed until it cannulates the ampulla of Vater before contrast is injected to visualise the biliary tree. Therapeutic procedures such as biliary stenting, removal of stones or balloon dilatation can then be performed. Conventional practice is obtaining CT imaging or an MRCP before a therapeutic ERCP.

Liver biopsy

Ultimately, histology can give a definitive answer as to the cause of hepatocellular injury. There are multiple ways of taking a liver biopsy, including:

- Percutaneous: using ultrasound or CT guiding with a transthoracic or subcostal approach

- Transvenous: the preferred approach for patients with coagulopathy due to a lower risk of bleeding. Interventional radiologists perform this procedure, and a transjugular approach is used.

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided: ultrasound imaging is used to guide an endoscopic biopsy needle

- Laparoscopic: often used to biopsy lesions found incidentally during routine laparoscopic surgery

Liver tissue can be reviewed to assess the degree of inflammation/fibrosis, exclude malignancy, and look for Mallory-Denk bodies (typical in alcoholic hepatitis due to intracellular oxidative stress).

Management of jaundice

There is no “standard management” of jaundice, as the underlying condition causing jaundice should be managed.

Common management strategies include:

- Supportive management for patients with cirrhosis: cirrhosis is not a curative condition, and so management is focused on minimising symptoms. This may include medication such as carvedilol (non-selective beta blocker) to reduce the risk of variceal bleeding and therapeutic ascitic paracentesis (ascitic drainage) to reduce discomfort from tense ascites. Patients with cirrhosis are also screened with ultrasound every six months for hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Antibiotics: for patients who have jaundice caused by an infective bacterial cause (e.g. ascending cholangitis/cholecystitis)

- Endoscopic removal of gallstones obstructing the common bile duct (ERCP)

- Support with alcohol cessation: patients may be referred to community or in-hospital alcohol teams. Detox regimens can also be used in hospital settings with benzodiazepines (commonly lorazepam or chlordiazepoxide) and vitamin replacement (intravenous thiamine/B12 in the form of Pabrinex).

- Ursodeoxycholic acid is a medication used for patients with gallstone disease. It reduces the production of gallstones by removing some bile acids.

- Symptomatic management of pruritis caused by jaundice: colestyramine is a bile acid sequestrant (i.e. it prevents reabsorption of bile acids). It can reduce pruritis in primary biliary cirrhosis or obstructive biliary pathology.

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Patient.info. Jaundice – Causes and Treatment. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient.info. Haemolytic Anaemia: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient.info. Gilbert’s Syndrome: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment. Published in 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE CKS. Hepatitis A. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient.info. Cirrhosis (End Stage Liver Disease). Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient.info. Dubin-Johnson Syndrome. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient info. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Radiopaedia.org. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. Published in 2023. Available from: [LINK]

Image references

- Figure 1. CDC/Dr. Thomas F. Sellers/Emory University. License: [Public domain]

- Figure 2. Rim Halaby / Wikidoc. Bilirubin metabolism. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 3. James Heilman, MD. Hepaticfailure. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 4. Dr. Gannavarapu Narasimhamurthy. Caput Medusae. License: [CC BY-SA]