- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Myocarditis refers to inflammation of the myocardium, the muscular layer of the heart. The highest risk is in men aged 20 to 40.1,2 The widespread availability and use of cardiac MRI in some countries have led to an increase in the reported incidence of myocarditis.

Myocarditis accounted for 0.04% of all hospital admissions in England between 1998 and 2017. However, due to the broad presentation and the overlap with other acute cardiac conditions, it is still believed to be under-recognised.1,2

The all-cause mortality in the UK for patients presenting to hospital with acute myocarditis is around 4%.2

Aetiology

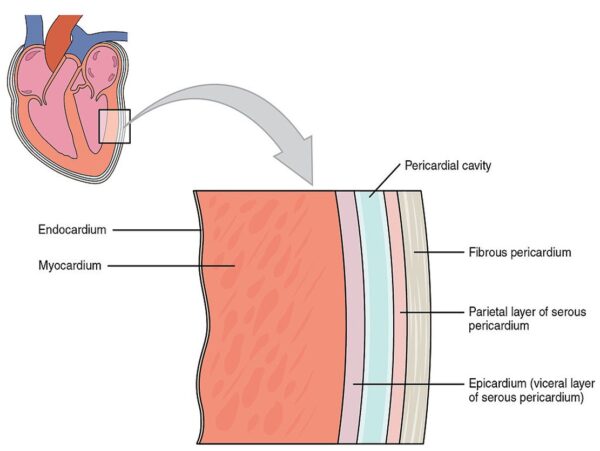

Anatomy

The heart’s wall is formed by three layers: the endocardium, myocardium, and epicardium. The endocardium is the innermost layer, which lines the cavities and valves.

The myocardium is the middle layer formed by cardiac myocytes, which depolarise autonomously under the influence of the sinoatrial node, causing them to contract so that blood can be ejected from the heart.

The final and outermost layer is the epicardium, formed by the visceral layer of the pericardium and directly overlies the myocardium.

Causes of myocarditis

The causes of myocarditis are broadly classified into infectious and non-infectious categories. In most cases (50%), no cause can be identified (idiopathic).

The most common aetiology in patients with an identified cause is a viral infection.3

Viral infections can inflict damage on cardiac myocytes through direct injury and secondary immune reactions, leading to myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. While viral myocarditis or cardiomyopathy is a complication of systemic infection of cardiotropic viruses, most individuals infected with these viruses do not develop significant cardiac disease.5

Some of the infectious and non-infectious causes are listed below:4

- Infectious: viral (e.g. coxsackievirus, parvovirus B-19, human herpesvirus 6 and Epstein-Barr virus), bacterial (e.g. staphylococcus, streptococcus and mycobacterium), fungal (e.g. aspergillus, candida and histoplasma) and parasitic (e.g. leishmania)

- Immune-mediated: allergens (e.g. vaccines and medications like penicillin), alloimmune (e.g. rejection after heart transplant) and autoimmune (systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis and thyrotoxicosis)

- Toxins: illicit drugs (e.g. amphetamines), alcohol, medications (e.g. lithium and clozapine) and radiation

Risk factors

Risk factors for myocarditis include:

- Age: younger people, typically those aged under 50 years old, are at a greater risk of developing myocarditis

- Sex: myocarditis is more common in men

- Immunocompromised patients: individuals with certain comorbidities like diabetes or HIV/AIDS, or those receiving cancer treatments or steroids, are more likely to develop myocarditis as they are immunocompromised

- History of autoimmune disease: if the patient has a history of an autoimmune disease associated with myocarditis, they are more at risk

- Alcohol and drugs: alcohol consumption, medications and illicit drug consumption have been associated with increased risk of developing myocarditis

Clinical features

The symptoms and signs of myocarditis can be varied as the presentation can be fulminant (cardiogenic shock), acute (less than 1 month) or chronic (over 1 month).2

History

Symptoms of myocarditis are a consequence of inflammation, heart failure and arrhythmias.

Typical symptoms of myocarditis include:4

- Chest pain: a very common symptom. The chest pain may be described as a squeezing or heavy discomfort, that may radiate to the neck, jaw or down the arms, mimicking the presentation of an acute coronary syndrome. Other times the pain may be described as central, worse on inspiration (pleuritic) and relieved by leaning forwards, which suggests an associated pericarditis.

- Shortness of breath: the patient may describe new or worsening shortness of breath on exertion or at rest. They may also report breathlessness when lying flat (orthopnoea) or breathlessness waking them from sleep which is relieved by sitting upright (paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea).

- Palpitations

- Dizziness

- Syncope

- Fatigue

Other areas of the history may help identify an underlying cause:2

- Systems review: an infective cause should be suspected if there were prodromal symptoms of fever, sore throat, myalgia, cough, vomiting or diarrhoea. An underlying autoimmune condition should be considered if there are reports of rash, hair loss, changes to bowel habits or uveitis.

- Past medical and surgical history: a known diagnosis of certain autoimmune conditions or a history of heart transplant may raise suspicion of myocarditis.

- Medications: ask about any recent vaccinations or changes to medications.

- Family history: to screen for an inherited cardiomyopathy or autoimmune disease.

- Social history: establish alcohol consumption, illicit drug use and recent travel.

Clinical examination

All patients with suspected myocarditis should undergo a full cardiovascular examination.

The cardiovascular examination may be normal, or there may be signs consistent with heart failure, arrhythmia or an underlying cause:6

- Tachypnoea

- Gallop rhythm

- Raised jugular venous pressure (JVP)

- Peripheral pitting oedema

- Inspiratory crackles

- Arrhythmias: palpation of a pulse may reveal a fast or slow heart rate

- Rash

- Ocular inflammation

- Lymphadenopathy

Pericardial rub and signs of cardiac tamponade (muffled heart sounds, hypotension and raised JVP) may be evident if there is co-existing pericarditis and pericardial effusion.

In severe cases, myocarditis may present as cardiogenic shock (systolic blood pressure <90mmHg, pulmonary congestion or elevated left ventricular pressure and signs of impaired organ perfusion) or sudden cardiac death.

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnoses of myocarditis can be divided into cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal causes:6

- Cardiovascular: acute coronary syndrome (which includes STEMI, NSTEMI and unstable angina), pericarditis, valvular heart disease (e.g. aortic valve stenosis), aortic dissection, primary cardiac arrhythmia and endocarditis

- Respiratory: pneumonia, pneumothorax and pulmonary embolism

- Gastrointestinal: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and oesophagitis

- Musculoskeletal: costochondritis and rib fracture

If the presentation is fulminant with haemodynamic instability, consider sepsis.

Investigations

Bedside investigations

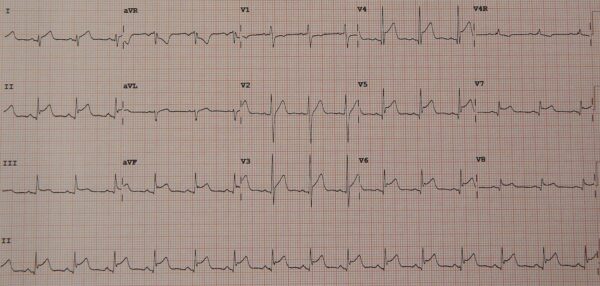

A 12-lead electrocardiogram is essential when assessing a patient with chest pain.

In myocarditis, the ECG is usually abnormal and most commonly shows sinus tachycardia with or without ST segment or T wave changes. The ST segment changes in myocarditis tend to be concave (convex in ischaemia) and present in most leads without reciprocal changes.

Other ECG findings in myocarditis include atrioventricular block, QTc interval prolongation and PR segment depression.4,6

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:4,6

- Full blood count (FBC): a full blood count is useful to help identify anaemia and sepsis.

- CRP and ESR: often raised in myocarditis.

- Troponin: very likely to be elevated due to inflammation in the heart muscle

- Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP): increased in the presence of elevated intraventricular pressures, suggesting heart failure.

- Urea and electrolytes (U&Es): to assess for evidence of end-organ dysfunction, which is important in those presenting with cardiogenic shock.

- Liver function tests (LFTs): may be deranged in the presence of viral hepatitis or end-organ dysfunction.

It is recommended to do an autoimmune screen for those with ‘clinically suspected’ myocarditis. However, routine viral serology is not recommended because a positive serology result does not imply myocardial infection. Therefore, performing viral serology is only recommended if there is clinical suspicion of a viral cause (e.g. hepatitis C and HIV).1

Imaging

Recommended imaging in suspected myocarditis includes:

- Chest X-Ray: will often be normal in myocarditis, but it may show features consistent with heart failure (alveolar oedema, bilateral pleural effusions, cardiomegaly and Kerley B lines). Cardiomegaly should also raise suspicion of pericardial effusion.6

- Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) can rule out valvular disease, which can mimic symptoms and signs of myocarditis.

- Cardiac MRI: can identify areas of myocardium affected by hyperaemia, oedema and necrosis, all indicative of inflammation. It is the non-invasive diagnostic test of choice when myocarditis is suspected, and it can produce useful structural, functional and prognostic information, too.1,2

In myocarditis, TTE is particularly useful to look for a pericardial effusion and other structural and functional abnormalities associated with myocarditis, like systolic or diastolic dysfunction, dilated cardiomyopathy, wall motion abnormalities or ventricular thrombus.4

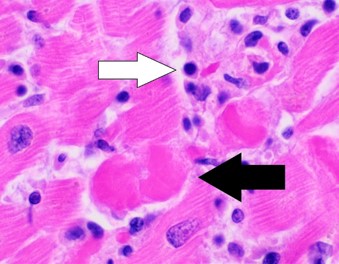

Other investigations

Endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) is the gold-standard diagnostic test. It is an invasive procedure which involves placing a catheter into the heart chambers via the radial or femoral arteries so that a biopsy can be made. The tissue sample is then sent for histology, immunohistochemistry and viral polymerase chain reaction.

If the tissue sample reveals inflammatory infiltrate with necrosis, a diagnosis of myocarditis can be made. This technique also has the advantage of identifying subtypes of myocarditis, which can help identify a cause, guide treatment and inform prognosis.

This procedure comes with its risks hence, current guidelines suggest only performing EMB if the following high-risk features are present:1,4

- Cardiogenic shock

- Acute heart failure requiring inotropic or mechanical support

- Ventricular arrhythmias

- Mobitz type II atrioventricular block or higher

EMB can also be considered if there is strong clinical suspicion of identifying a treatable disorder (e.g. an autoimmune condition). Otherwise, cardiac MRI is the investigation of choice in the absence of high-risk features.1,4

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of myocarditis is made after EMB if the biopsy specimen shows histological evidence of inflammatory infiltrates with myocyte degeneration and necrosis of non-ischaemic origin. This is known as the Dallas criteria.1,4

However, as mentioned above, an EMB is invasive and poses risks, so it is not routinely performed. In most cases, a cardiac MRI is diagnostic.

Without histology, patients are referred to as having ‘clinically suspected myocarditis’ if they have one or more clinical presentation features and one or more diagnostic criteria from different categories. This is summarised in the table below.1,4

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for clinically suspected myocarditis.

| Clinical presentation | Diagnostic criteria |

| Acute chest pain | ECG or Holter monitoring demonstrating electrocardiographic changes seen in myocarditis |

| New or worsening shortness of breath on exertion/at rest | Elevated troponin |

| Palpitations or syncope | Evidence of functional abnormalities on cardiac imaging, and no other pathology that could account for the presentation |

| Unexplained cardiogenic shock | Cardiac MRI showing evidence of myocarditis |

| History of recent viral infection |

Management

Initial management

In the acute setting of myocarditis, treatment is supportive and may involve the management of pain, acute decompensated heart failure, cardiogenic shock and arrhythmia.

If there is pleuritic pain suggesting pericardial involvement, treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and colchicine can be considered.

Those presenting with features of acute decompensated heart failure should be treated with oxygen, non-invasive ventilation (if appropriate) and intravenous diuretic therapy. Vasodilator therapy should be considered if there is an inadequate response to diuresis.

Alternatively, if a patient presents with cardiogenic shock, treatment options may include inotropes, vasopressors or mechanical support (e.g. intra-aortic balloon pump, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or left ventricular assist device).

Patients with myocarditis can also develop arrhythmias:

- Bradyarrhythmias (Mobitz II or complete heart block): temporary pacing is required

- Tachyarrhythmias with an adverse feature: synchronised direct current cardioversion should be used as per the resuscitation council guidance

- Narrow complex tachyarrhythmias: antiarrhythmics or rate-limiting medications, the choice of which is guided by the underlying rhythm.1,4 For more information please see the articles on the acute management of atrial fibrillation and narrow complex tachcyardia.

If there is any evidence of cardiac tamponade, a pericardial drain is needed.

Long-term management

Once a patient is stable, if they have developed heart failure, then medications should be started to manage this:1,4

- Diuretics

- ACE-inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers

- Beta-blockers

- Sodium-glucose transport 2 inhibitors

- Aldosterone receptor antagonists

It is also advised that patients avoid exercise for three to six months.1,4

If an autoimmune cause is identified, immunosuppressive treatment should be considered after discussion with the appropriate specialist.

Complications

Complications of myocarditis include:5

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

- Heart failure

- Arrhythmias

- Pericardial effusion/tamponade

- Sudden cardiac death

Most patients with myocarditis will have a spontaneous resolution in a few weeks. Factors that predict a poor prognosis include:6

- Cardiogenic shock

- Reduced ejection fraction on imaging

- Ventricular arrhythmias

- Heart block

Patients who have diagnosed or clinically suspected myocarditis should be followed up within a few months in clinic to consider repeat ECG, troponin and echocardiography. If there is concern for ongoing myocyte damage, repeat cardiac MRI and EMB can be considered.4,6

Key points

- Myocarditis is inflammation of the heart muscle

- Although a cause is often not found, viral infections are the most commonly identified cause of myocarditis in developed countries

- Typical symptoms include chest pain, which may be pleuritic or pseudo-ischaemic, new or worsening shortness of breath or palpitations

- Examination findings can be quite varied, from a normal examination to someone presenting with cardiogenic shock

- Key investigations are troponin, ECG, echocardiography and cardiac MRI

- The gold standard diagnostic test is EMB, but if this is not indicated, then a cardiac MRI is the best non-invasive test.

- Management in the acute setting is supportive and often involves treatment of heart failure and arrhythmias

- Long term management focuses on the treatment of heart failure and arrhythmias with close follow-up

Reviewer

Dr Shivasankar Sukumar

Cardiology Registrar (ST5)

Editor

Dr Jess Speller

References

- Basso C. Myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(16):1488-500.

- Lampejo T, Durkin SM, Bhatt N, Guttmann O. Acute myocarditis: aetiology, diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2021;21(5):e505-e10.

- Tschöpe C, Ammirati E, Bozkurt B, Caforio ALP, Cooper LT, Felix SB, et al. Myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: current evidence and future directions. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(3):169-93.

- Caforio AL, Pankuweit S, Arbustini E, Basso C, Gimeno-Blanes J, Felix SB, et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(33):2636-48, 48a-48d.

- Yajima T. Viral myocarditis: potential defense mechanisms within the cardiomyocyte against virus infection. Future Microbiol. 2011;6(5):551-66.

- Bagshaw C. Causes and management of myocarditis. Kendall J, editor. [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 12]. Available from: [LINK]

Images

- Figure 1. OpenStax College. Layers of the heart wall. License: [CC BY 3.0]

- Figure 2. James Heilman, MD. Diffuse ST segment elevation in myopericarditis. License: [CC BY-SA 4.0]

- Figure 3. Mikael Häggström, M.D. Histopathology of lymphocytic myocarditis. License: [CC0]