- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Most of what you see in emergency medicine will not be an emergency. However, as an emergency physician, you must consider and rule out the worst-case scenarios.

In this article, we will go through common ED presentations encountered in majors focusing on serious diagnoses and how to manage them.

Consultant sign-off and senior review

Remember that you are working as part of a team, and you should feel empowered to ask your seniors for advice and support in decision making.

When starting in emergency medicine, you may be asked to discuss all patients with a senior clinician. However, as you gain experience, you will start to act more autonomously as a decision maker.

The Royal College of Emergency Medicine has identified the following high-risk patient groups which require a consultant sign-off before discharge:

- Atraumatic chest pain in patients over 30

- Patients who re-attend within 72 hours for the same presentation

- Abdominal pain in those over 70

- Fever in children under one

You should check with your local department at induction, as additional presentations may require a sign-off. Most departments will also accept review by a registrar where an ED consultant is unavailable.

Chest pain

The causes of chest pain can be broken down according to the body system involved:

- Cardiac causes (e.g. acute coronary syndrome, aortic dissection and pericarditis)

- Respiratory causes (e.g. pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax and pneumonia)

- Gastrointestinal causes (e.g. gastro-oesophageal reflux, gastritis and peptic ulcer disease)

- Musculoskeletal causes (e.g. costochondritis, rib fractures or muscular injuries)

Using a structured SOCRATES approach can help you gather the relevant information you need to start narrowing down this broad differential.

Acute coronary syndrome

This umbrella term includes ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina.

In a typical patient, the structured SOCRATES history will reveal a central chest pain or heaviness that radiates to the jaw and arms and is associated with marked sweating (diaphoresis), nausea, and breathlessness.

However, remember that patients can and do present atypically. This is especially true of diabetics who are at risk of having a ‘silent MI’.

During the history taking, make sure you ask about risk factors such as a history of ischaemic heart disease, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia and a family history of heart disease. These will raise your suspicion of acute coronary syndrome.

ACS definitions

STEMI: ST elevation and a raised troponin.

NSTEMI: Normal ECG or T wave inversion associated with a raised troponin.

Unstable angina: Normal ECG and normal troponin but with cardiac-sounding chest pain on minimal exertion or at rest.

Investigations

All patients with cardiac-sounding chest pain should have an ECG as soon as possible after arriving in the department.

It is important to consider the timing of the chest pain in relation to the troponin test. Cardiac troponins T and I reach a peak 12-48 hours after myocardial injury.1

However, the advent of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays (hs-cTn) has meant we can detect a troponin rise much earlier. Your department will have a policy on what cut-off troponin is acceptable in relation to the timing of the chest pain.

Performing a repeat troponin can add additional diagnostic value. For example, a static troponin is less concerning and may reflect an alternative underlying cause, such as impaired renal function. On the other hand, a dynamic troponin is suggestive of myocardial ischaemia.

Treatment

All patients with an ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) should be discussed immediately with the cath lab for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) and stenting. Do not wait for the troponin result. Time is muscle.

Treat NSTEMIs and unstable angina as per your hospital guidelines. Typical management includes morphine, oxygen (if low O2 only), nitrates (e.g. GTN), aspirin and a second antiplatelet such as clopidogrel.

Tip – chest pain

All patients with cardiac-sounding chest pain should have an ECG as soon as possible after triage.

If you see ST elevation, discuss immediately with the cath lab for consideration for primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Pulmonary embolism (PE)

Pulmonary emboli can range in clinical severity from small subsegmental clots to a massive saddle embolus, causing right heart strain and haemodynamic instability. It is essential to consider a PE in anyone with pleuritic chest pain, sudden onset shortness of breath or collapse.

Risk factors include active cancer, recent surgery, obesity, DVT, prolonged period of immobility, pregnancy and medication such as the combined oral contraceptive pill.

Investigations

ECG findings in pulmonary emboli are not always present. When present, the most common ECG findings are sinus tachycardia or signs of right heart strain (right bundle branch block and right axis deviation). Unlike in medical exams, the classic S1Q3T3 pattern is rarely seen!

If considering a PE, you should use a scoring system such as the Well’s criteria to risk stratify the patient.2 This will determine how to investigate them best. A D-dimer alone should not be used to rule out a PE in high-risk patients due to the risk of a false negative result.

A CT pulmonary angiogram is the gold standard investigation for a pulmonary embolism in a high-risk patient or a low-risk patient with a positive D-dimer.

Management

Massive pulmonary emboli with haemodynamic instability may require thrombolysis. These patients need high-level care and should be discussed with senior ED and medical team members.

Non-critical cases are treated with oral anticoagulation.

All patients must be followed up with consideration given to underlying causes such as thrombophilia or underlying malignancy.

Low-risk patients who are seen out of hours with a suspected PE may be discharged and booked into an ambulatory unit to have a CTPA the next day. Scoring systems such as the simplified PESI score can be used to risk-stratify these patients.3

Remember that If discharging a patient home, you should cover them with treatment dose low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) while they wait for their scan.

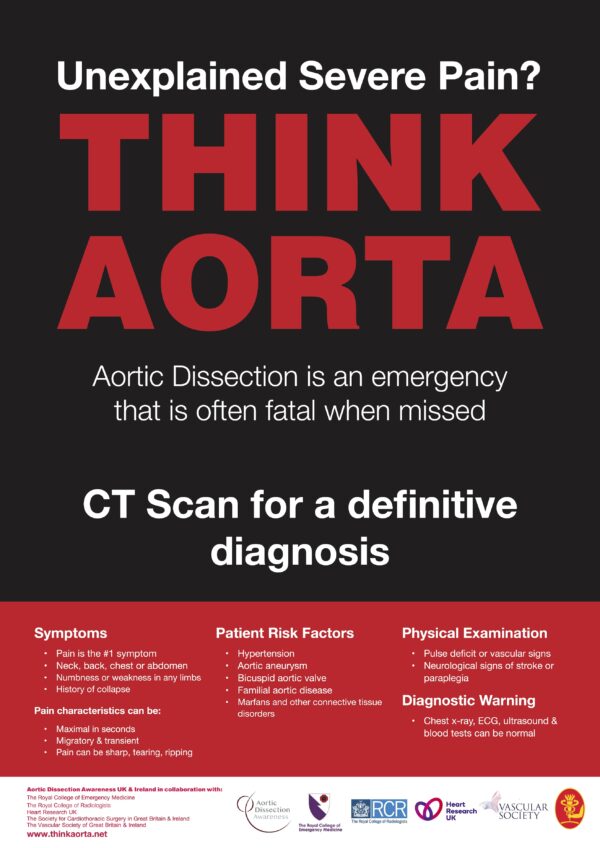

Aortic dissection

An aortic dissection describes a tear in the intimal layer of the aortic wall, creating a false lumen. This is a catastrophic diagnosis associated with a high mortality rate. The Stanford classification categorises them into type A and type B dissections:

- Type A dissections involve the ascending aorta with or without involvement of the arch and descending aorta

- Type B dissections affect only the descending aorta distal to the left subclavian artery

Acute aortic dissections are difficult to diagnose due to the varied clinical presentation and the lack of sensitivity and specificity of the clinical signs and investigations.

The classical presentation is that of a severe, sudden onset, tearing chest pain which is maximal at the point of onset and which radiates through to the back. However, patients do not always present typically.

Atypical features include neurological deficits, abdominal pain or limb ischaemia. Additionally, patients can be relatively comfortable when you see them in the ED as the pain is maximally present at the point of onset. A high index of suspicion and a careful history taking them back to the onset of the chest pain is needed.

Investigations

Your clinical examination should include feeling for a radio-radial delay, listening for aortic regurgitation and measuring blood pressure in both arms.

A chest X-ray can help look for a widened mediastinum, and the troponin and D-dimer levels may also be elevated in certain cases. If present, these may raise your index of suspicion, but none of them are sufficiently sensitive to rule out a dissection.

A CT angiogram of the aorta is the definitive investigation in patients suspected of having an aortic dissection.

Tip

Aortic dissections are diagnostically challenging and associated with a high mortality.

Senior input must be sought for all cases of severe, sudden onset chest pain, shock or unexplained neurology.

A CT angiogram of the aorta is the only investigation which can rule out a dissection.

Management

These patients can be critically unwell and should be managed with an ABCDE approach.

The focus is on lowering the blood pressure in hypertensive patients and giving adequate analgesia. Type A dissections should be discussed urgently with cardiothoracic surgery for consideration of surgical repair. Type B dissections also require urgent cardiothoracic input but are often medically managed with blood pressure-lowering medication in the initial stages.

Shortness of breath

Pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism (discussed above) is an important differential for patients presenting with shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, syncope, collapse or haemoptysis.

Asthma / COPD

Asthma

Asthma exacerbations are usually non-infective and may be triggered by environmental factors or a viral illness. It is essential to gauge the severity of their asthma. Severe asthmatics who have previously required ITU admission can deteriorate quickly and should be managed aggressively.

Features of life threatening asthma include SpO2 < 92%, PaO2 <8kPa, exhaustion, altered conscious level and a normal PCO2.4

Remember that tachypnoea in an asthmatic normally results in blowing off carbon dioxide and a subsequent low pCO2. A normal or elevated pCO2 is, therefore, a concerning sign.

A peak expiratory flow of 33-50% and an inability to complete full sentences without the above features suggest acute severe asthma.4

COPD

Patients with COPD often have ‘rescue packs’ at home, and they may come in after having tried a course of antibiotics and steroids already.

Gauging the severity of the patient’s COPD is important. You should enquire about the patient’s baseline oxygen saturation, whether or not they use ambulatory oxygen therapy at home and if they have required non-invasive ventilation (NIV) in the past.

COPD patients should be managed with a target oxygen saturation of 88-92%, as those with chronic hypercapnia rely on a hypoxic drive to maintain their respiratory effort.5

Maintaining O2 levels between 88-92% in all patients with COPD has been shown to reduce inpatient hospital mortality.6

Investigations for asthma / COPD

A venous blood gas (VBG) is sufficient in the emergency department to determine the patient’s blood pH and whether or not they are retaining carbon dioxide. However, it is inaccurate in measuring the extent of hypercapnia and will not give an arterial O2 reading.7

Baseline blood tests and a chest X-ray will help determine whether or not the patient has an infective component to their exacerbation.

Management

Table 1. Acute management of asthma and COPD

| Asthma | COPD |

| Salbutamol (back-to-back nebulisers if needed) | Salbutamol (back-to-back nebulisers if needed) |

| Ipratropium bromide (three to four times a day) | Ipratropium bromide (three to four times a day) |

| Oxygen (94-98%) | Oxygen (88-92%) |

| Steroids | Steroids |

| Antibiotics if infective cause suspected | Antibiotics if infective cause suspected |

| IV magnesium and IV salbutamol may be needed in severe cases | NIV may be needed in severe cases |

| Get help if not improving. Alert ITU early in life-threatening asthma. | Get help if not improving. Critical care outreach can help set up NIV if required. |

Pneumonia

A chest infection should be at the top of your differential for anyone presenting with shortness of breath, cough and a fever.

Be alert for atypical presentations. For example, consolidation at the base of the lungs due to lower lobe pneumonia can sometimes present with abdominal pain.

Investigations

Scoring systems such as the CURB-65 score can help determine the severity of the infection.8 Checking the patient’s inflammatory markers and requesting a chest X-ray will also help you in this assessment.

Management

Pneumonia can be divided into community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP). Check your local hospital guidelines, as the antibiotic choice may differ in both cases.

Sending a sputum sample and checking for previous sensitivities can help guide treatment, especially in cases where empirical antibiotic treatment has failed.

Pneumothorax

Pneumothoraces can be spontaneous or traumatic. Spontaneous pneumothoraces can be subdivided further into primary or secondary depending on the patient’s age and the presence or absence of underlying lung disease.

Symptoms include sudden onset shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain. However, patients may also be asymptomatic.

A chest X-ray is the investigation of choice, although they may also be diagnosed on CT in cases of trauma.

Management

The treatment of a spontaneous pneumothorax depends on the clinical picture and can range from conservative management with outpatient follow-up to a chest drain insertion and inpatient care. The British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines include a helpful decision tree to guide management.9

A traumatic pneumothorax is a pneumothorax which results from an injury to the chest wall. These may be associated with multiple rib fractures and a haemothorax, which should be managed with a surgical chest drain.

A tension pneumothorax can develop from a spontaneous pneumothorax or, more commonly, a traumatic pneumothorax. The trapping of air in a tension pneumothorax results in compression of the mediastinal great vessels, causing haemodynamic compromise.

Clinical signs include absent breath sounds on the affected side, deviation of the trachea to the opposite side, distended neck veins and low blood pressure.

Tip

Rapid deterioration of a patient with a known or suspected pneumothorax should raise the suspicion of a tension pneumothorax.

A tension pneumothorax is managed by immediate decompression of the affected side. The 2nd intercostal space (ICS) in the mid-clavicular line and the 5th ICS anterior to the mid-axillary line can be used.

As a junior doctor starting in the emergency department, you will not be expected to perform invasive procedures alone. Get help early from a senior doctor if you suspect a tension pneumothorax, and use this as an opportunity to gain some valuable emergency medicine skills.

Other causes of shortness of breath

There are many other causes of shortness of breath to consider, such as pleural effusion, congestive cardiac failure, and anaemia. Performing a thorough history and examination is always the first step to getting the correct diagnosis. If you are unsure, discuss the patient with a registrar or consultant.

Abdominal pain

There are many organs in the abdomen and, consequently, many potential causes of abdominal pain. A thorough abdominal pain history and examination is your most valuable tool in differentiating between these causes.

The acute abdomen

While it may take you a while before you get to the underlying cause of the patient’s pain, one crucial distinction you can make early on is whether or not the patient has an acute surgical abdomen.

Guarding, rebound or percussion tenderness are all signs of peritonitis and indicate an acute pathology requiring input from the surgical team. You should involve the surgical team early in cases where the above signs are elicited. It is unnecessary to wait for the results of blood tests or imaging before contacting them.

Be aware that a high body mass index can make it more difficult to elicit signs of peritonitis due to the quantity of adipose tissue between your hands and the inflamed peritoneum.

Your initial management in a patient with an acute abdomen is the same, irrespective of the underlying diagnosis. This includes keeping the patient nil by mouth, giving analgesia, IV fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics if you suspect a perforation. This initial approach will be the same for appendicitis, diverticulitis, cholecystitis and perforated bowel.

Investigations in acute abdominal pain should include an ‘abdominal profile’ consisting of a full blood count, renal function, liver function tests and an amylase. A urine dip is also important if you suspect a UTI, ectopic pregnancy or renal colic (where blood will often be seen).

All women of childbearing age who present with acute abdominal pain should have a urine pregnancy test.

Bowel obstruction

You should suspect bowel obstruction in patients who present with abdominal pain and a cessation in bowel motions or flatus. Bowel obstruction may also be associated with poor appetite, nausea and faeculent vomiting.

Examination findings include abdominal distension and tinkling bowel sounds. The diagnosis can be confirmed with an abdominal X-ray or CT. The initial management is the same as that for an acute abdomen but also includes decompression of the obstruction with a nasogastric (NG) tube.

Hernias

The examination of common hernia sites (umbilical, inguinal and femoral) is essential to the abdominal examination.

Ensure the patient is lying flat when examining them and that the femoral and inguinal areas are exposed. Obstructed or incarcerated hernias will be firm, irreducible and tender. All patients with an obstructed or incarcerated hernia require an inpatient surgical review.

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

This is a life-threatening condition which has a pre-hospital mortality of 50% and an untreated mortality approaching 100%.10

The aorta is considered dilated if it is over three centimetres, and the risk of rupture increases with size. It is estimated that the yearly risk of rupture is one per cent in a 4.0-4.9 centimetre AAA and 11% in a 5.0-5.9 centimetre AAA.11

A high index of suspicion is needed to make the diagnosis as only 25-50% of patients present with the classic triad of abdominal pain radiating to the back, hypotension and a pulsatile mass.10

Alert your seniors to any cases of unexplained abdominal pain or collapse, especially in the older population. ED consultants and trained registrars can perform a point-of-care ultrasound scan looking for an AAA. However, a CT angiogram of the aorta is the definitive investigation and should be requested if an ultrasound cannot be performed or is inconclusive.

Renal colic

Renal colic is extremely painful. You can often spot these patients queueing to book themselves in as they will be doubled over and holding onto their flank. The classic presentation is a severe crampy loin to groin pain.

Most of these patients will have microscopic haematuria due to the trauma caused by the passing stone.

Giving adequate analgesia is a priority, and PR diclofenac is very effective for this type of pain.

An infected, obstructed stone is a urological emergency, so look for signs of infection such as fever, positive urine dip and raised inflammatory markers. Septic patients with an obstructed stone require urgent urological intervention.

The investigation of choice to look for renal calculi is a CT KUB (CT of the kidneys, ureters and bladder). Patients with a kidney stone should be discussed with the urology team. Those with small and distal ureteric calculi can usually be discharged home with a renal stone advice leaflet and follow up with the local renal stone clinic.

Testicular torsion

Don’t forget the genitals! Testicular torsion can also cause lower abdominal pain, especially in children where the pain is more poorly localised.

Torsion may occur in all age groups but is most common soon after birth and between 12-18 years.12 Clinical signs include a tender, high-riding testicle with an absent cremasteric reflex. You should discuss all suspected cases with your seniors or the on-call urology team.

Gynaecological causes

Gynaecological causes of acute abdominal pain include ruptured ovarian cyst, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ovarian torsion and endometriosis.

Specific points to remember in gynaecological history taking include gravidity and parity (remembering to ask about previous abortions, ectopics or miscarriages), last menstrual period, vaginal bleeding, discharge and a sexual history (including sexually transmitted infections and dyspareunia). Approach these topics delicately and with empathy. However, do not shy away from asking all the important questions.

Tip

All women of childbearing age with abdominal pain should have a urine pregnancy test.

Ectopic pregnancy

This should be considered in any woman with abdominal pain in early pregnancy who has not yet had a confirmed intrauterine pregnancy on the initial dating scan. Unilateral lower abdominal pain associated with vaginal bleeding is the most common presentation.

Risk factors include smoking, increased maternal age, use of an IUD, previous ectopic pregnancy, tubal damage and previous pelvic infections.

Referral to the on-call gynaecology team is required in all suspected cases of an ectopic pregnancy.

In rare cases, patients may present ‘in extremis’ with haemodynamic shock following a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. These patients should be managed as a major haemorrhage call and early senior input is required.

Who to refer to?

It may not be immediately obvious whether the patient’s pain is surgical or gynaecological. For example, a woman who is 8 weeks pregnant and presents with sudden onset right iliac fossa pain could have an ectopic pregnancy or appendicitis. In these cases, liaising with the on-call surgical and gynaecology team is necessary to develop an appropriate management plan.

Try to avoid getting stuck in the middle of conversations between specialities. If you are leaning more towards an ectopic pregnancy as the underlying cause, then it would be appropriate to refer to the O&G team and ask them to liaise with the surgical team if an ectopic pregnancy is excluded.

Medical causes

There are many medical causes of abdominal pain which should be considered. This includes gastroenteritis, peptic ulcer disease, inflammatory bowel disease, lower lobe pneumonia and diabetic ketoacidosis.

Gastritis and peptic ulcer disease

Gastritis and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) are common conditions. However, they are overdiagnosed in the emergency department. If the patient is in severe pain or there are signs of gastrointestinal bleeding, then you should consider perforation from a peptic ulcer.

Erect chest X-rays are not sufficiently sensitive to exclude a perforated ulcer, and the imaging of choice in these cases is a CT scan of the abdomen.

Various scoring systems, such as the Glasgow-Blatchford Score, can be used to identify patients at low risk following a suspected GI bleed and who can be managed as an outpatient.13 High-risk patients should be managed in an inpatient setting.

A rectal examination is important in all cases of suspected GI bleeding to look for melaena. In any patient with non-specific abdominal pain, the presence of melaena or frank blood on a PR exam can provide a vital clue to the underlying cause.

Tip

There are many possible causes of acute abdominal pain, and a thorough history and examination are crucial to narrowing down this broad differential.

Involve the surgical team early if the patient is presenting with signs of peritonitis.

Elderly patients with abdominal pain are at high risk of significant pathology and should always be discussed with a senior before discharge.

Falls in the elderly

There are two key questions to consider in an elderly patient who has fallen:

- Why did they fall?

- What injuries have they sustained?

Why did they fall?

Falls in the elderly are multifactorial, and you should not label the fall as ‘mechanical’ until you have fully considered other causes.

It is helpful to break down your fall history into events before, during and after the fall:

- Before the fall: Were there any pre-syncopal features? Did they have chest pain or palpitations before the fall? Had they just stood up or got out of bed, suggesting a postural drop? How have they been feeling lately? Has there been an intercurrent illness? Are there any signs of a chest or urine infection?

- During the fall: Was this a witnessed fall? Did they lose consciousness? What was the mechanism (e.g. did they fall down the stairs or fall from standing)? Was there any seizure-like activity? Did they bite their tongue, or were they incontinent of urine?

- After the fall: How quick was the recovery period? Were they ‘postictal’ or confused? Was there a long lie? Have they been able to get up and mobilise since the fall?

Investigations

Bedside investigations such as an ECG and lying standing blood pressure are essential components of a falls workup in the elderly.

A VBG is a quick way of looking for any significant physiological abnormalities (lactate, pH, electrolyte abnormalities and blood glucose).

Routine blood tests may also be helpful in a falls ‘MOT’, including a full blood count, inflammatory markers, renal function and creatinine kinase (CK) if there was a long lie (due to the risk of rhabdomyolysis).

What injuries have they sustained?

Silver trauma

Older people can sustain significant injuries despite a relatively benign mechanism, such as falling from standing.

Silver trauma is a term used to refer to trauma in elderly patients, and it is an important concept in emergency medicine. Older patients respond to trauma differently. Osteoporotic fractures are possible following only minor injuries, and medications such as beta-blockers may mask a tachycardic response to internal bleeding.

Primary survey

Your ‘primary survey’ in elderly trauma should follow the structured ABCDE in major trauma approach.

It is worth reiterating here that the physiological parameters you are used to in a younger population may not apply to the elderly. For example, a background of hypertension and atherosclerosis will make them less tolerant to prolonged periods of hypoperfusion, b-blockade can mask a tachycardic response, and anticoagulant use increases the risk of internal bleeding.

Secondary survey

You should perform a thorough top to toe assessment of all elderly patients who have fallen after life-threatening injuries have been managed in the primary survey.

Start with the head and neck and work your way down. This includes the head, cervical spine, thoracic and lumbar spine, chest wall, abdomen, hips, wrists and long bones. Palpate each of these areas thoroughly, looking for underlying injuries.

Make sure to expose each area as you examine it to look for hidden bruising or wounds. Be thorough and ask a senior clinician for help with imaging decision-making if unsure.

Have a low threshold for obtaining an X-ray of the pelvis and hips. A fractured neck of femur is common in the elderly and associated with poor outcomes if missed.

During medical school and your OSCE exams, you will have had a lot of practice in going through the motions of performing a physical examination in artificial patients. However, in the emergency department, remember that these are real patients. It seems an obvious point to raise, but it is a common mistake for someone to say that they are examining the chest without truly examining it!

Look all over for bruising and wounds. Feel the trachea and for chest wall expansion. Palpate thoroughly, including anterior, lateral and posterior aspects of the chest wall, looking for underlying rib fractures, flail segments and crepitus. Auscultate the lung fields anteriorly and posteriorly.

Use your eyes and your hands to do the detective work. There isn’t an OSCE examiner marking you as you go through the motions. It’s just you and the patient!

Head injury

Head injuries can range from minor bumps to major trauma. Understanding the mechanism of injury is key to gaining an appreciation of the severity of the injury.

Patients who have sustained a major trauma or who have a significant mechanism of injury should be assessed using the ABCDE approach with spinal immobilisation until you can assess and clear the cervical spine.

Patients who walk into the ED with a minor head injury are unlikely to require spinal immobilisation and scoring systems such as the Canadian C-spine rules can be used to help decide which patients require imaging.14

History taking

Important features in the history include whether or not there was a loss of consciousness, amnesia, drowsiness, seizures, focal neurology, nausea or vomiting.

Examination

You should perform a neurological examination looking for focal signs with careful attention to signs of basal skull fracture such as haemotympanum, panda eyes, postauricular bruising and CSF leak. However, be aware that these are often late signs, which will only be present in the most severe head injuries.

Investigations

CT head: NICE guidelines in the UK have a useful algorithm for deciding when a patient requires imaging with a CT head.15

All adult patients with the following findings should have a CT head within 1 hour:

- All patients with a GCS of 12 or less in the ED

- GCS of less than 15 two hours after the injury

- Suspected open or depressed skull fracture

- Any signs of basal skull fracture (haemotympanum, panda eyes, CSF leak, battle’s sign)

- Post-traumatic seizure

- Focal neurology

- More than one episode of vomiting.

A CT head scan is also indicated in other high-risk patients where there has been a loss of consciousness or amnesia (e.g. dangerous mechanism, prolonged amnesia or presence of bleeding disorders), and a scan should be considered in those who are on anticoagulants or antiplatelets (except aspirin monotherapy).

Going home post-head injury

When discharging a patient following a minor head injury, you should give them verbal and written safety netting advice.

This will highlight what symptoms they can expect after a head injury (e.g. mild headache, dizziness, poor concentration, sleep disturbance) as well as concerning features which would necessitate a return to the ED (e.g. severe headache, vomiting, new neurology).

Your department should have a head injury advice leaflet which can be given to the patient and their carer. Anyone being discharged home following a head injury should be advised to stay with a responsible adult for at least 24 hours post-injury.

Conclusion

One of the most exciting aspects of emergency medicine is the combination of the detective work needed to diagnose undifferentiated patients and the practical skills required to provide immediate and lifesaving treatment.

This guide has given you a flavour of the most common emergency department “majors” presentations and how to approach them. However, it is by no means an exhaustive list. With each new patient, take a systematic approach, ask for help and advice when needed, and enjoy the learning experience.

The art and craft of medicine is built on the back of individual patient encounters. I am sure you will find your time in the emergency department a hugely valuable experience!

References

- Laza, D.R. et al. National library of medicine. High sensitivity troponin: a review on characteristics, assessment and clinical implications. 28/03/2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Wells, P. MD+ Calc. Wells’ criteria for pulmonary embolism. Accessed Nov. 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Jiménez, D. MD+ Calc. Simplified PESI (pulmonary embolism severity index). Accessed Nov. 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- British Thoracic Society. BTS/SIGN guideline for the management of asthma. July 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Paha, P. et al. National library of medicine. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compensatory measures. 26/06/2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Echevarria, C. et al. BMJ Emergency Medicine Journal. Oxygen therapy and inpatient mortality in COPD exacerbation. March 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Nickson, C. Life in the fast lane. VBG versus ABG. 03/11/2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Macfarlane, J. MD+ Calc. CURB-65 score for pneumonia severity. Accessed Nov. 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Roberts, M. E. et al. BMJ Thorax. British Thoracic Society guideline for pleural disease. 08/08/23. Available from: [LINK]

- Jeanmonod, D. et al. National library of medicine. Abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture. 08/08/2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Owens, D.K. et al. Journal of the American Medical Association. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: US preventive service task force recommendation statement. 30/10/2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Lacy, A. Et al. The American journal of emergency medicine. High risk and low prevalence disease: testicular torsion. April 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Blatchford, O. MD+ Calc. Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score. Accessed Nov. 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Stiell, I. MD+ Calc. Canadian c-spine rule. Accessed Nov. 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Head injury: assessment and early management. 18/05/2023. Available from: [LINK]